Wood blewit mushrooms (Clitocybe/Lepista) are a treat to find and an even bigger treat for the cooking pan and taste buds. These eye-catching mushrooms are hunted with enthusiasm. Identifying the wood blewit can be a little challenging – surprisingly, it’s extremely easy to walk right on by this beautiful species. This is because the blewit is a master of disguise; it likes to keep the mushroom hunter on their toes!

This isn’t an impossible mushroom to identify. It’s actually an excellent beginner mushroom because it teaches patience and investigative skills, as well as forces the forager to pay attention to details. It also gives a glimpse into the fungi kingdom’s incredible and often quite frustrating transmutational nature.

Many props to Australian Free Food Forager Ingrid Button for the fun and very memorable Purple Nudist name

Jump to:

All About Wood Blewit Mushrooms

The beautiful light lilac-colored blewit mushroom is found worldwide but is most common in Europe and North America. It is a late-season mushroom, which might also contribute to its immense popularity. It is a delicious mushroom, but all the more so when there is literally nothing else to be found in the woods.

The taxonomic history of the wood blewit is a nightmarish mess, so you may see this mushroom species under a host of different names. This is one case in which the common name saves it from being a complete disaster. It is the only wood blewit, no matter where it is placed on the taxonomic tree.

Wood blewits are interchangeably listed as Clitocybe nuda or Lepista nuda, and even sometimes Tricholoma nuda, depending on who you ask and probably what side of the pond you’re on. Or, possibly just by picking a name out of a hat. If you have more than one identification book, it’s a fun game to guess which name the author used in their description of this fungi.

Most North American guides lean towards Clitocybe nuda (FYI, Clitocybe is pronounced CLY-toss-a-bee).

Wood Blewit Identification

Season

Late autumn into winter, depending on the climate.

Habitat

These mushrooms grow singularly from the ground but are often found in larger scattered groupings. They like wood floors rich with organic material, meadows and grasslands, and even urban and suburban mulched areas.

Identification

Cap

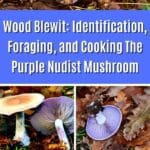

Wood blewit caps start out as a wonderful violet or lilac color that really stands out in the brown autumn woods. The shades of purple range from bright to very light lavender and even purply pink or a very dull lilac. They are rounded with cap edges that are rolled inwards to create a beautiful button.

It doesn’t take long, though, for the color and shape to morph into something that doesn’t stand out at all as anything special. The attractive, eye-catching lilac purple turns mauve to dull tan, starting at the center of the cap. The entire cap is an unremarkable brown color in a short time, resembling so many other mushrooms.

If you catch them at the right time, you’ll find the mushroom in mid-color transformation, with some lilac still around the edges, although the center is entirely tan – this is a foraging clue to what you’ve stumbled upon. Once they go full brown(ish), it’s extremely and rather unbearably easy to completely miss them in the leaf litter or mulch. They blend right in.

As the caps age, they also flatten out, losing the rolled edges. Eventually, they’ll flatten out entirely and then start lifting upwards to create a concave center. It’s common to find leaves and debris in the center of the caps at this stage. As the edges outstretch, they also become wavy and uneven.

The caps range from 1.5 – 6 inches in diameter. They are smooth, without any decorations, and are usually tacky when wet.

Gills

The gills are attached to the stem, very close together, and range in color from very light lilac to pinkish or tannish. Sometimes, they can be quite vibrant, but often they’re rather understated. They do not stain or change color when cut or bruised.

Stem

The stem usually matches the color of the gills quite closely. It also ranges from pale lilac to pinkish to brownish, turning more brown as it ages. The stem grows up to 2.5 inches long and is equal in length down to the bulbous base.

Flesh

The flesh of the wood blewit is also lilac or light purple. It is soft and thick and does not change color when cut.

Smell

Has a pleasant fragrant smell, like sweet citrus or bright floral. It is very distinctive.

Spore Print

Pinkish

On The Lookout

The wood blewit exists to make sure we do not dismiss any mushrooms as dull (I’m pretty sure…). If you want to find this mushroom, you HAVE to pay attention to bland tan mushrooms out in the woods. If you’re lucky, you’ll find some still in their lovely lilac cap phase to alert you to their presence.

If you see something promisingly wood blewit-like, upon further investigation, there should be some signs of the lilac/purple/lavender beginnings. Either the gills or the stem will probably still hold a little bit of that unmistakable color to alert you to its identity. This, of course, means that you must fully investigate the mushroom – it is unlikely you’ll know it for what it is from just a top view.

Don’t forget to smell them! That should give you a clue, even if you didn’t find any remaining lavender coloring. And, of course, do a spore print.

Blewits rarely grow alone. If you find one, definitely look for more nearby! They will also return to the same spot yearly, so mark your locations.

Wood Blewit Lookalikes

There are many lookalikes, but they are easy to differentiate once you know what you’re looking for.

Purple Corts (Cortinarius species)

There are quite a few Cortinarius mushrooms that are purple or purple-adjacent and may get confused with the blewit. Corts have several telltale features, though, that set them apart. When young, they have universal veils that cover their gills. As they mature, the veil breaks, leaving thin cotton-like remnants around the gills and a circular marking around the upper portion of the stem.

Even if these things aren’t obvious, you can be sure you’ve got a Cortinarius species by doing a spore print. Their spores are brown.

Field Blewit (Clitocybe saeva/Lepista saeva)

This species is primarily in Europe. For a long time, it was thought not to occur in North America. However, there are reports of it in California. It looks incredibly similar to the wood blewit, except it does not start out lilac. It is brown from the beginning. It is also a fine and widely foraged edible species.

Laccaria amethystina

The amethyst-deceiver is very purple when young, just like the wood blewit, then fades with age, also like the wood blewit. It grows in mixed forests in eastern North America and other temperate regions. This mushroom is much smaller than the wood blewit, with a cap that doesn’t get bigger than 2.5 inches wide. It also has a thinner and hollow stem with no bulbous base. It does not have a distinctive smell.

While the amethyst-deceiver is edible, it isn’t considered choice. Basically, it doesn’t taste that great, but if you’re starving, go ahead and eat it; you won’t die.

Laccaria amethysteo-occidentalis

This violet mushroom occurs in western North America and is quite common. It is very similar to the eastern amethyst-deceiver, except it only grows in conifer forests. The caps are much smaller than the wood blewit and usually have a noticeable depression in the center of the cap. If in doubt, do a spore print. The spore print on this one is white.

Clitocybe tarda

This relative of the wood blewit shows its kinship with light lavender to pinkish cap and gill coloring, which also fades over time. It is significantly smaller than the blewit, in stature and depth, with brittle, thin flesh. The stem is slender, with no bulbous base, and the cap doesn’t get much larger than 2.5 inches wide. It looks like the younger cousin of the blewit, but not as brown. It is also edible but doesn’t have much texture, so it isn’t commonly gathered.

Cooking with Wood Blewits

A word of caution with this species: even though it is widely consumed, it is known to be digestively disagreeable to some folks. So, eat just a small amount at first to be sure you’re okay with it.

Cooking with blewits is very much like cooking with the common button mushroom. They’re firm, slice well, and shed a lot of water during cooking. Any recipe you use button mushrooms in, you can substitute them with blewits. This is if they are cooked – never eat blewits raw.

Their flavor is also quite similar to button mushrooms – mushroomy and lovely, but nothing out of this world spectacular. They can be a little slimy after cooking, so it’s best to put them in a recipe where they’re well incorporated, like a stew, stir-fry, or casserole. Serving them on their own doesn’t show off their best side.

Wood Blewit Recipes

Wood Blewits Common Questions

Doesn’t purple indicate a mushroom is poisonous?

No. Color has nothing to do with a mushroom’s poisonous or toxic nature. One of the most deadly mushrooms, the destroying angel, is entirely white. Please do not use (or repeat) broad generalizations about mushroom toxicity based on coloring; it leads to many false assumptions and mistakes.

Are wood blewits medicinal?

No, it is not known as a medicinal mushroom.

Can I grow wood blewits?

Yes, wood blewit mushrooms can be cultivated. They are commercially cultivated in several European countries. Here’s a very neat and super simple Blewit cultivation method from Tradd Cotter.

Interested in other purple/blue mushrooms? Check out our in-depth guide to the Indigo Milky Cap, bright blue and bleeds, too!

Leave a Reply