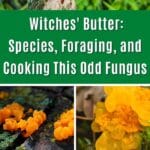

Witches’ butter is a common name applied to several different fungi species. The species are quite different in terms of genetics, but to the eyes, they’re very challenging to tell apart. Thank goodness, none of these witches’ butter are toxic. In fact, they’re all edible, and in some cultures, a delicacy!

Will the real witches’ butter please stand up?

Jump to:

All About Witch’s Butter

The fun (and funny) common name, witch’s butter, comes from the yellow coloring and gelatinous, perhaps spreadable texture. This could be a good fit if witches use butter (do they?). Or, perhaps the buttery fungus fell off the witches’ toast as they soared over the treetops, leaving yellow splats on dead wood and logs? That’s the folklore I’m creating for this brilliant fungus [see the real folklore further down].

Other common names for witches’ butter include golden jelly fungus, yellow brain, and yellow trembler. The actual fungi species this name refers to could be one of several, depending on who you’re talking to. This is one of the issues with common names; yes, they make the fungi easier to remember, but they are also so much more complicated when one name refers to many species.

Instead of choosing which yellow blobby fungi mass deserves the sole use of the name witches butter, I’m going to lay them all out for you.

- Tremella mesenterica

- Tremella aurantia (Naematelia aurantia)

- Dacrymyces chrysospermus (formally Dacrymyces palmata)

Witches’ butter fungi are globular, jelly-like, gelatinous blobs that light up the forest. They are bright yellow to yellow-orange, to bright orange, depending on the species. And they’re found all over the world. Witches’ butter is one of the most well-known, widespread fungi; even if you didn’t know what you’re looking at, you’ve probably seen it.

These fungi grow on dead or almost dead logs and branches. They can appear year-round but are known for their winter growth. You can still hunt the witch butter when there is nothing else to forage.

None of these species are thought to be particularly tasty. They are edible in that they’re not toxic but aren’t considered to be a culinary delight. Of course, this varies by culture. In Asian cultures, there is much more acceptance and use of witches’ butter species. It is commonly used to make a healing soup.

The globular texture is likely seriously off-putting to many. And the flavor is rather bland. But, it can be cooked up nicely or added to bulk up soups and add a different texture. Some guides list it as inedible only because they don’t find it enjoyable or worthwhile. We’ll let you be the decider of that – but give it a try first before dismissing it.

In addition to the yellow and orange witches’ butter species, there’s also brown (Tremella foliacea), black (Exidia glandulosa), and snow white (Tremella fuciformis) witches’ butter species. And, to keep the gendering of fungi even, a Warlock’s Butter, too (Exidia nigricans).

The Folklore of Witches’ Butter

Witches’ butter often sprouts from the soft wood of exposed door frames, especially in times before chemical sealants. In Eastern European folklore, if you found witches’ butter fruiting from your door frame, it meant that a spell had been placed on your house and family. The only to remove the spell was to pierce the bright gelatinous mushroom with a sharp object and drain out the juices. Although, it must have been very freaky to see the witches’ butter return all the time – once a piece of wood is infected, it stays infected!

In Swedish folklore, witches’ butter is formed when a bunch of witches gather together and steal milk from a family’s cows. After milking the cows, the witches leave, scattering bits of “butter” on the ground.

In yet another folk myth, it was believed that a person could defend themselves from witchcraft by tossing witches’ butter fungus into a roaring fire.

The Primary Witches’ Butter Species

Tremella mesenterica

T. mesenterica is parasitic on another fungi species — a fungus that parasitizes a parasitic fungus! Say that five times fast! In this case, it attacks fungus in the genus Peniophora.

The Peniophora are crust-like fungi that form on dead and dying logs and twigs. Some Peniophora are parasitic themselves, while most are saprobic (they just eat the decaying material, they don’t cause the decay).

This witches’ butter contender actually grows directly from the Peniophora fungi it is parasitizing. This isn’t always easy to see, but if you look closely at other parts of the stick or log, you might still see the crust fungus.

T. mesenterica witches’ butter is found on hardwoods in deciduous and mixed forests. It grows up to 3 inches across, 1-2 inches high, and features multiple lobes or a convoluted, wavy growth. The fungi are bright, deep yellow, or yellow-orange; sometimes, they are much lighter yellow, too. The fruiting bodies are slimy and look wet and greasy. If you poke them, they will jiggle and move.

The lifecycle of this witches’ butter is relatively simple. It appears during or after rainy periods, breaking through crevices in the bark. It radiates its bright jiggly body for a few days, inviting everyone to check it out.

After a few days, the fungus dries out, turning into a shriveled, thin goop. It is fully capable of reviving after receiving more water. When it is dry, it is hard and smooth. The dried bodies of this witches’ butter are deep amber brown to dark reddish-orange.

T. mesenterica grows across North and South America, Asia, Africa, Australia, and Europe. Fun Fact: Tremella mesenterica translates to “trembling middle intestines.” How’s that for a descriptive name!

Key Identification Points:

- Bright yellow to yellow-orange to light yellow.

- With age, darkens to reddish-orange or brown amber

- Gelatinous, slimy, goopy

- Grows in small convoluted masses, averaging 3 inches across and 1-2 inches tall

- Grows on Peniophora crust fungi, on dead hardwood logs and branches.

- Often difficult to see the crust fungi beneath the witches’ butter fungi

- Breaks through the bark as it grows

Tremella aurantia (Naematelia aurantia)

This second Tremella (now Naematelia) contender for the witches’ butter name looks very much like its sibling described above. They are often confused and quite challenging to differentiate. Their coloring is very similar, a bright yellow to yellow-orange.

T. aurantia is parasitic on the fungus, Stereum hirsutum. And S. hirsutum is a disease that affects plants – it’s also known as false turkey tail or hairy curtain crust. It’s a strange circular world of attacking, parasitizing, and surviving!

It is easier to see the S. hirsutum specimen beneath this witches’ butter, as opposed to T. mesenterica. Stereum hirsutum is a bracket fungus, not a crust fungus. This means it stands out more, standing upright with a body a quarter inch to 1.5 inches wide.

This witches’ butter, also commonly known as golden ear in North America, grows up to 6 inches across and features the same lobed or convoluted growth. It will also produce frond-like growth, similar to seaweed.

The primary difference in overall appearance between this fungus and T. mesenterica is that this one has a more matte-like coloring. It isn’t as shiny, slimy, or greasy looking. It is still very gelatinous, though. In addition, its lobes and folds are thicker and denser. When it dries up, it retains its shape. This is very different from T. mesenterica, which shrivels as it dries.

T. aurantia appears on broadleaf trees in North and South America, northern Asia, and Europe. It is not as widespread as T. mesenterica.

Key Identification Points:

- Yellow to yellow-orange, more matte-like coloring than shiny

- Gelatinous, goopy, but not super greasy looking

- Grows on hardwoods

- Grows in globular masses or as fronds, like forked seaweed clumps

- When it dries up, the shape is retained

- Often still possible to see parasitized host still on wood (bracket fungus S. hirsutum).

Dacrymyces chrysospermus (aka Dacrymyces palmatus)

The third contender for the name witches butter is pretty different and easier to tell apart from the other two similar species. D. chrysospermus is known as orange witches’ butter or orange jelly, or if you’re in the UK, orange jelly spot. As you can probably guess, this fungi species is much more orange in color than the other witches’ butter.

Also, unlike the other two witches’ butter contenders, this fungi species is not parasitic. It is only saprotrophic, meaning it feeds off dead or dying wood; it does not kill it. And the wood D. chrysospermus chooses is also different from the other two, which grow on deciduous trees – this species is only found on dead and dying conifer trees.

It emerges from the cracks in the wood bark and rarely grows from branches with intact bark; it needs the cracks to be there already to squeeze through. Because of this, it is often found on very well-rotted conifer wood.

Orange jelly fungus bodies grow up to 2.4 inches across and are gelatinous, shiny, and bright orange. They vary widely in shape but often have a cup or spoon-shaped base. They might form as individual little spoons or tongues sticking up from the wood or merge into a single goopy mass.

When the fungus dries out, it turns reddish-brown and becomes more translucent. This witches’ butter species is most commonly found in winter. It grows across North America, Europe, and worldwide.

Key Identification Points:

- Bright orange to orange yellow

- Globular, slimy, jelly-like masses

- May grow singular frond-like bodies or merge together to form small gelatinous masses

- Grows on conifers, emerging from already existing cracks in the bark

- Turns reddish-brown when it dries out

Medicinal Witches’ Butter Fungus

Chinese medicine considers the Golden Ear mushroom (witches’ butter, species Naematelia aurantialba, previously Tremella aurantialba) to be a warm food. It is used to create a nutritional tonic to treat and alleviate cold symptoms. Specifically, it is used to soothe coughs and reduce phlegm.

This fungus is also used to improve metabolism and is thought to contain anti-aging properties. Traditional practitioners also prescribe it to inhibit tumor cell growth.

Witches’ Butter Lookalikes

Dacrymyces capitatus & Dacrymyces stillatus

These two Dacrymyces species are orangish-yellow (or yellowish-orange) but appear more as dots or singular blobs than the witches’ butter specimens. Sometimes, the dots merge together, but even then, you can make out the individual specimens.

This is very unlike the witches’ butter, which is lobed, brain-like, small masses that intertwine. Witches’ butter looks more like a clump of goopy jelly fell off a spoon onto the countertop, while D. captiatus and D. stillatus look like someone piped the jelly out of a piping bag. Of course, there are many variances between individual specimens and collections, but overall, these are the general appearance differences.

Cooking and Eating Witches’ Butter Fungi

Many folks refer to witches’ butter as “survival food,” meaning the only reason to eat it is if there’s nothing else in the pantry. Or, if the zombie apocalypse has happened, civilization has collapsed, and now you’re relying on your foraging skills to stay alive.

For these purposes, witches’ butter is an excellent fungus to know. It is relatively easy to identify, even if you’re unsure which of the three species it is, and it doesn’t have toxic lookalikes.

There is some debate over whether it can be eaten raw. This probably depends on your individual digestive hardiness, but technically, it’s okay. I won’t promise you won’t have repercussions, though. We always recommend cooking any wild mushrooms to make them more palatable and easier to digest.

Witches’ butter mushrooms don’t have much of a flavor; none of them do. These fungi soak up the flavors of whatever they are added to and add an interesting texture to the dish. They are most often used in soups, stir-fries, curries, and stews. Witches’ butter also dries and dehydrates quickly and easily.

Some people report feeling a cool menthol-like effect on their tongue when eating raw witches’ butter. It has a bit of a tingly effect. This may be why the fungi are used to treat lung-related issues as a medicine.

When cooked, witches’ butter mushrooms retain their rubberiness, but it’s just a slightly chewy texture. Several sources say when it is roasted, it resembles fried pork rinds. We’ve also heard it compared to fried calamari when deep fried.

Witches Butter Recipes

There isn’t much online for recipes that include this fungus. In Chinese, it is known as Golden Ear Fungus, so that is the best way to search out recipes. If you cook with any of the witches’ butter specimens, we’d love to hear how you prepare it!

Common Questions About Witches’ Butter

Is witch’s butter poisonous?

No. None of the species listed here are toxic to eat. Of course, any mushroom (and any food) has the potential of causing intestinal distress or an allergic reaction. Eat just a little bit at first to make sure your body agrees.

What is witches’ butter used for?

It is an edible fungus, but mostly it is valued for its purported medicinal qualities.

Leave a Reply