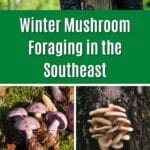

The southeast United States has a lot of fungi in winter, more than most other regions. The lack of severely cold temperatures and generally warm days is prime for many mushroom species. Winter foraging in the southeast is often excellent, with so much lurking in the woods waiting to be discovered. Even in areas where it snows, it doesn’t usually last long enough to seriously impact growth.

If you live in the southeast and are a mushroom forager, count your blessings and get out in those woods. You may need to do some extra searching to find edible species, but they’re definitely out there.

Check out the guides for other seasons, too: Spring Mushroom Foraging in the Southeast, Summer Mushroom Foraging in the Southeast, and Fall Mushroom Foraging in the Southeast.

Winter Mushroom Foraging In The Southeast

Lion’s Mane

One of the best things about lion’s mane being a late fall/winter mushroom is that it’s bright white coloring is easier to see when there are no leaves on the trees. The unique white spines and often immense size stand out in a stark, gray forest.

Lion’s mane is a top edible mushroom species; it tastes reminiscent of seafood! This mushroom only grows on trees and often high up. Unfortunately, this means they can be challenging to harvest. But, if you’re ardent and the location allows it, returning with a ladder is always an option. This forager has stood on the roof of her car with a long pole to reach one along a dirt road (don’t recommend this, but in a pinch if you’re steady-footed…). Carrying a long stick with a basket (lacrosse goalie stick) helps a lot with foraging lion’s mane!

Lion’s mane is also a prime medicinal mushroom with many documented benefits. It is commonly included in functional mushroom blends, whether it be supplements, teas, or energy drinks. If you’re interested in the medicinal side of Lion’s Mane, check out this article, What is Lion’s Mane? A Comprehensive Guide To The Popular Medicinal Mushroom

Brick Caps

Brick caps adore cool weather but dislike snow, making the not-too-cold southern states ideal. These are an early winter species, as once it gets into the cold depth of winter, they die back. The great thing about bricks caps is that they’re often found in dense quantities around dead stumps. Finding these means mushroom eating for days.

Only forage brick caps if you are absolutely confident in their identification. They have a dangerous cousin that is known to grow alongside it on occasion. Sulfur tufts are yellower, lacking the distinctive brick red marking of the brick cap, but still can be sneaky. Always check each specimen before adding it to the frying pan.

Wood Blewit

The wood blewit, aka the purple nudist, appears only after the summer heat is gone but doesn’t usually hang around for the deep cold of winter nights. This is generally an early-season winter mushroom. In warmer winters, it may appear later. It is not uncommon to find this striking mushroom in the middle of winter with a dusting of snow on top, and it’s still just fine.

Wood blewits are a good edible species with a flavor similar to the common storebought button mushroom. They’re not at the top of the edibles list, but in winter, when there isn’t a whole lot to choose from, finding a patch of wood blewits is marvelous.

Oysters

True oyster mushrooms (Pleurotus spp.) are big fans of cool weather. As long as there are no long extended periods of freezing temps, you can potentially forage oyster mushrooms all winter season. The mushrooms might freeze on the tree, but as long as you catch them before they thaw and begin decomposing, they’ll still be good eating.

Oyster mushrooms grow from trees and stumps, and the lack of foliage makes it easier to see them in winter. They tend in fruit in giant groupings, sometimes covering an entire tree or log – such a treat to find a bounty like this in the dreariness of the winter months! There are several types of oyster mushrooms growing in North America. Some are more prone to appearing in late fall and winter, but all do appreciate the cooler temperatures.

This forager has found oyster mushrooms the size of dinner plates in February (and danced for joy in the woods). One of the greatest things about winter oyster mushroom finds is that they aren’t as infested with bugs, and they decompose slower, meaning you’re more likely to find some good-eating ones. Oyster mushrooms are a prime edible species with a dense, meaty texture that holds up very well during cooking.

Late Fall Oysters

Even though not a “true” oyster mushroom, the late fall oyster is a top fruiting species in fall and winter. Don’t let the name fool you into thinking it can only be found in the fall. These mushrooms generally don’t even show up until there’s been a frost or two – that’s how much they love the cold. They’re more common in northern regions, but if you live in the mountains where it’s colder you’ll likely see this one. Folks that live more southerly might not encounter the late fall oyster.

Late fall oysters are known for holding up for a long time in the cool weather, unlike true oysters, which tend to deteriorate rather quickly.

The texture of late fall oysters is a wee bit slimy, but they’re great in stews to bulk it up or made into mushroom jerky. They are super dense, meaty, and a bit chewy. This forager has found late fall oysters frozen on trees, still perfectly prime for harvesting. The freezing cold actually probably helped preserve them.

Velvet Foot Enoki

Wild enoki is also known as “the winter mushroom,” a name it truly earns. It doesn’t look anything like its cultivated cousin, not even a little bit. Many people are shocked to learn that velvet foot enoki, and the grocery store enoki is the same species.

Keep an eye out for this winter mushroom all season long. It adores cold weather, and it’s not unusual to find it frozen to the tree or covered in a layer of snow or ice. The velvet foot enoki has an extremely dangerous lookalike, aptly named the deadly galerina. Only forage this species if you are beyond certain of your identification. When in doubt, always do a spore print!

Witches’ Butter

Bright yellow-orange jelly-like blobs are hard to miss, making witch’s butter an easy winter mushroom to see. This species is edible but probably isn’t for everyone. It’s slimy, gelatinous, and has a slightly chewy texture. It also doesn’t have any distinctive taste. However, while other mushrooms tend to be scarce, this one is super common.

It can be added to soups and stews to bulk them up or tossed in with a stir-fry. Some consider these lil bright orange blobs to be a delicacy. They’re worth a try at least once and an excellent survivalist species to know.

Wood Ear

Wood ears are an excellent edible mushroom with a weird ear shape that is a bit disarming. They grow all winter long, often in large groupings or clusters, and are pretty easy to identify. Usually, wood ears appear in late fall, and then the cool weather allows them to hang out for quite a while before decomposing. This makes wood ears top among the winter mushroom foraging species.

These mushrooms are a bit rubbery and don’t have much taste, but they’ll take on the flavor of whatever they’re cooked with. And they add a wonderful denseness to recipes, with a slight chewy crunch. They’re really quite unique.

Wood ears are excellent in brothy soups and stir-fries. They’re also a medicinal species, traditionally used to treat high cholesterol, regulate blood sugars, and alleviate sore throats.

Amber Jellyroll

This is not a top edible species; in fact, some people might say it’s not edible at all. It’s gloopy, slimy, squishy, and tasteless. But, when there’s nothing else, the forests provide. Amber jelly roll fungus fruits year-round, and it is very widespread. It doesn’t mind the cold and is actually more common in cooler weather. No matter what you think about the look or texture, this species is edible.

Turkey Tail

Turkey tail grows year-round and is a small bracket mushroom that remains viable for a long time. So, even if it’s not actively growing, you may find growth from earlier in the season that is still good to harvest. Turkey tail is collected for its medicinal properties and used to make tea. Make sure you brush up on what false turkey tail looks like and how to tell the difference — there are a lot of small, bracket polypores in the woods.

Foraging Resources

If you’re new to mushroom foraging, here are some great guides to get started: How To Be A Successful Mushroom Forager, Mushroom Foraging 101, and Mushroom Identification Pictures and Examples.

This guide to the best identification books by region will help you find the best guides for you.

Curious about winter foraging in other areas? Check out our guides for across the US.

Leave a Reply