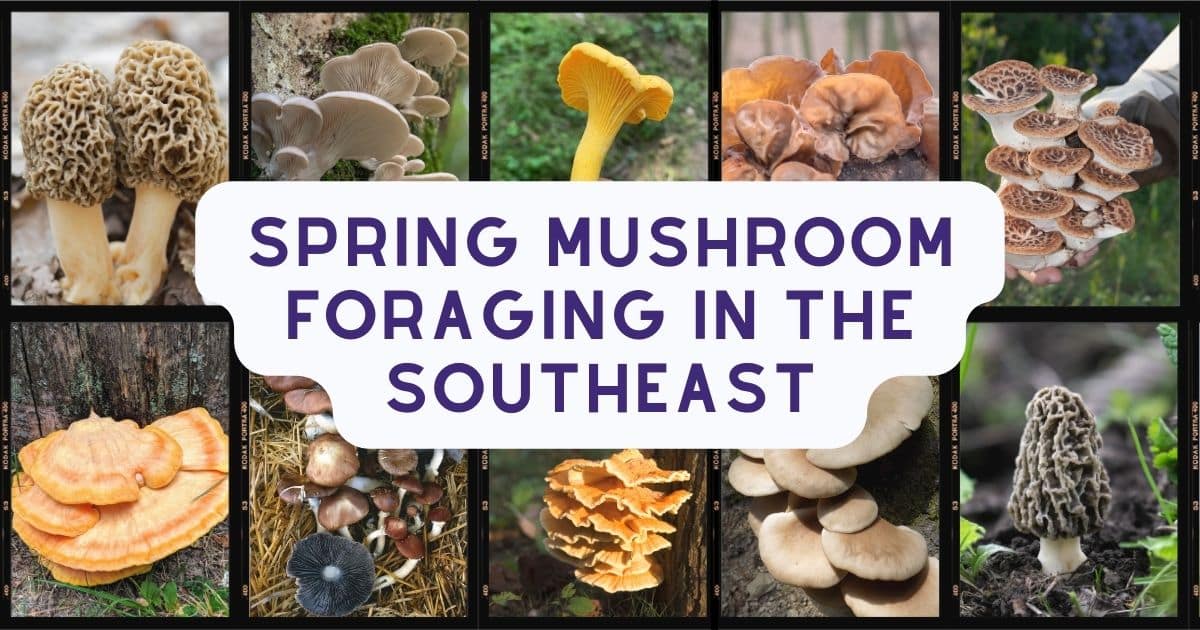

There’s a lot to forage in the southeast in spring. Many people get blinded by morels, but there is so much more happening at this time that every trip in the woods should be treated as a treasure hunt. Spring mushroom foraging in the southeast is a treat, with morels, chicken of the woods, oysters, and dryad’s saddle appearing early on. Then, in late spring (May to June), chanterelles and black trumpets start to pop up as it gets warmer.

Spring mushroom foraging in the southeast does come with its own special challenges – bugs, heat, and humidity are top on that list. But it’s not as bad as it gets in the summer months, so it’s good to get out in the woods adventuring while it’s still relatively cool.

The southwest foraging season never really ends, as it does in other regions of the country. Winter foraging in the southeast is also pretty fantastic. The spring season officially starts with the appearance of morels, though you may find some of the others before you find morels. Also check out our other seasonal guides for the region: Summer Mushroom Foraging in the Southeast and Fall Mushroom Foraging in the Southeast.

This guide covers the top 8 edible species to look for while spring mushroom foraging in the southeast. If you see any species you love to forage that are missing, please let me know.

Jump to:

Top Eight Spring Mushrooms In The Southeast

Morels (Morchella)

The beloved morel mushroom, known for its elusiveness and deliciousness, is a special treat that can only be found in the springtime. Unlike other mushrooms, morels do not grow at any other time of the year. Therefore, if you want to forage for these culinary delights, now is the time to venture out and start your search. Morels are quite abundant in the southeast if you find a stellar patch. One of the great things about morels is that they usually reappear in the same location year after year. So, once you find a spot, mark it well and visit it yearly to harvest.

Distinguishing characteristics of the morel mushroom include a cap with a pitted texture, a whitish stem, and a hollow interior. The cap’s attachment point to the stem can vary depending on the particular species, with some attaching in the middle or at the top of the inside of the cap. Additionally, the size of morels can differ significantly. Some are delicate and measure around 1-2 inches, while others are larger and more robust, reaching heights of 3-5 inches.

Morels make their appearance in very early spring, typically from mid-March to mid-April, depending on your location in the Southeast. Recently, they’ve been showing up consistently in early March. If you follow any foragers or groups from the south, you can keep tabs on when they will likely emerge. There’s always at least one person jubilantly posting their first finds on social media sites.

Once you start seeing a lot of posts, you know it’s time to get out there. The season starts in the south and gradually progresses northward as the weather becomes more favorable. So, those in the southernmost states should see them first. If you’re determined to find these elusive mushrooms, I highly recommend keeping a close eye on this progression so that you can hit the woods at the optimal time.

Many people say that morels appear when the lilacs bloom, which is generally a good marker for their fruiting. However, this can be misleading depending on the climate, season, and the lilac bushes. You may find yourself missing out on some morels if you’re solely basing your searches on when the lilacs bloom. It could be that most morel patches only fruit later, but who knows what you’re missing out on by not looking earlier.

The Facebook Group Morel Mushroom Find Reports is an excellent and reliable resource. Another great way to see where people are finding morels is the Morel Sightings Map, which is updated annually.

To give you an idea of the difference over the last several years, here are the first Morel sightings in the southeast as reported on the Morel Sightings Map.

- 2024 – last week of February, but mostly the first week of March

- 2023 – middle of February, but mostly first week of March

- 2022 – last week of February, but mostly the first week of March

- 2021 – first week of March

- 2020 – last week of February, but mostly the first week of March

- 2019 – first week of March

- 2018 – first week of March

An important point to consider when foraging morels (and any mushroom, really) is that elevation matters. Experienced foragers follow the morels up the mountains as the weather progressively warms on the mountaintops. This extends the season quite dramatically and can have you finding morels into June in cooler, higher elevation areas.

When searching for morels in the Southeast, the best places to look are around ash, tulip, and fruit trees. The list below shows that there is a range of habitat preferences depending on the species, but there is also a lot of overlap. In the Southeast, you may come across five different species of morels: three yellow morel species and two black morel species.

- Morchella americana – a yellow morel that grows with ash, elm, cottonwood, apple, and pear trees, among others. Looks gray when young, then develops yellowish brown ridges and pits.

- Morchella diminutiva – a yellow morel that prefers hardwoods like ash, hickory, and tulip. As the name suggests, this is a very small morel, rarely getting more than 2.5-3″ tall. Pits are dark gray when young but turn brownish-yellow with age.

- Morchella virginiana – a yellow morel that a preference for tulip trees and sandy soil, especially around riverbeds and coastal areas. When young, it has gray pits and yellow ridges. The pits turn yellowish-brown with age.

- Morchella angusticeps – a black morel that fruits around apple, cherry, tulip, and ash trees. When young, it is tan or yellowish-brown but darkens to black with age.

- Morchella punctipes – a half-free black morel with a cap smaller than other morels. It grows with hardwoods. The cap looks like a thimble setting atop a tall white stem.

Oyster Mushrooms (Pleurotus)

The cool-weather-loving oyster mushrooms (Pleurotus ostreatus) will show up in early spring, but they tend to disappear once the weather gets warmer. If the weather has been mild enough, they might even be around all winter. These are often a year-round species in the Southeast, depending on the region and the climate conditions that year. But they are less common in the heat and humidity of summer. P. ostreatus is most likely encountered in the first couple of months of spring.

These oyster mushrooms have light gray to brown caps, white to buff gills, and dense white flesh. They grow on deciduous hardwoods (trees that lose their leaves). Beech and aspen trees are common. Sometimes, they grow on conifers as well. Oyster mushrooms have a mild anise odor, meaning they smell a little sweet, like licorice.

The aspen oyster mushroom, also known as the spring oyster, is frequently seen in the spring season. It can be found mainly on quaking aspen trees but can also grow on other aspen species and cottonwoods. Aspen oysters smell faintly of anise or might just have a subtle mushroom scent.

The Phoenix oyster mushroom starts showing up as soon as the weather warms up, often from early April all the way through September. It likes warmer weather than the classic oyster, P. ostreatus. In fact, that’s often a good way to tell these two very similar species apart. P. ostreatus is more of a winter to early spring species, while the Phoenix oyster mushroom is a late spring to summer oyster mushroom species.

Veiled oyster mushrooms can be found year-round in the southern states. They like warm to mild climates and grow on dead and dying hardwood trees. Veiled oyster mushrooms look different from other oyster mushrooms because they have a veil around the gills and usually grow alone instead of in dense clusters.

The appearance of yellow oysters (Pleurotus citrinopileatus) in spring is pretty common in the southeast. They are a non-native species, escaped from cultivation, and like the cool weather of spring and fall. Yellow oyster mushrooms primarily thrive on hardwood trees, particularly elms, but they can also be found on oak, beech, and various other hardwood species.

These oyster mushrooms grow in large colonies, and taking all of them is fine since they’re not a native species. Finding a fruiting of these is very much like finding a golden jackpot – you’ll be eating good for days, maybe weeks.

Dryad’s Saddle (Cerioporus squamosus)

The odd-looking dryad’s saddle, also known as pheasant’s back polypore or hawk’s wing, often goes unnoticed and unappreciated due to its tendency to be tough in full maturity. However, it must be noted that this toughness only occurs when the mushroom is past its prime. When young, the dryad’s saddle is actually a delicious and highly sought-after edible. To dismiss it as “bad” would be like biting into a rotten apple and assuming all apples are gross. The key is to pick it at the right time.

The caps of the dryad’s saddle are beautifully decorated with dark brown brush strokes that make it look like a hawk’s wing or the feathers on a pheasant. The pore surface smells like watermelon rind or cucumber, a distinctive smell that sets it apart from other polypores. The dryad’s saddle has a unique crunchy texture and a more robust flavor compared to other mushrooms, making it a great addition to pickled dishes or those with bold flavors.

Chicken of The Woods (Laetiporus)

The highly sought-after chicken of the woods mushroom primarily grows in summer and fall, but in the southeast, it will also fruit in spring—sometimes even in late winter if you’re lucky. Just this year (2024), a forager reported a huge chicken of the woods find in the first week of March! This mushroom has its own agenda; no one can dictate its actions, so it’s a good idea to keep a lookout for it anytime you’re in the woods.

Chicken of the woods thrives on decaying wood, forming large clusters as it matures. It is important to check the condition of the mushroom before picking it, as it becomes tough and inedible with age. This wild mushroom species is one of the absolute best edibles with a dense, succulent texture and mild flavor.

Although chicken mushrooms do not taste identical to chicken, they do have a similar texture. There are various ways to prepare chicken mushrooms, such as poaching, frying, sautéing, baking, mincing, or coating with breadcrumbs. They also pair well with different flavors, including BBQ spices and sauce, poultry seasoning, ginger and garlic, and marinades. Their versatility makes them a great substitute for meat in vegetarian dishes.

Wine Caps (Stropharia rugosoannulata)

Wine caps thrive in cooler weather and fruit during both spring and fall. They can be found growing in wood chips and mulch, where they feed on decomposing organic matter. They are easily identifiable by their deep burgundy caps, unique cog-wheel-shaped ring on the stem, and gills, which start off as a pale gray before maturing into a dark purplish gray color. They can be found growing in the wild but are also commonly cultivated due to how easy they are to grow outdoors in gardens.

Renowned for their meaty texture and robust taste, wine caps are often used in dishes such as stuffed and baked, grilled, or risotto. They are similar to store-bought button mushrooms but superior in flavor.

Wood Ears (Auricularia)

The oddly human-ear-shaped wood ears have a gelatinous consistency and can be found growing on wood throughout the year. It is worth noting that not all brown jellies are actually wood ears, so it is crucial to be able to distinguish them from similar-looking mushrooms. Some may fall under the Exidia genus, such as amber jelly rolls, but luckily, they are still safe to eat. Although wood ears do not have a strong taste, they do provide a unique texture when used in soups and stir-fries. They can also be dehydrated and easily rehydrated with water.

Chanterelles (Cantharellus)

Most of us know chanterelles to be a summer mushroom, but in the southeast, you might also encounter them in late spring. Reports from southern states show a couple of chanterelle species showing up in early to mid-June, well ahead of other species. While you’re probably not going to find a ton of them, they’re definitely out there.

Chanterelles are one of the top edible wild mushroom species, with a lightly fruity smell, taste, and dense texture. When you’re out in the woods, keep an eye out for these forest treats! It helps to know where to look for them so you don’t miss out because you weren’t even looking. The two primary species that show up in late spring are:

- Cantharellus minor – this is the smallest of the golden chanterelles and is widespread east of the Rocky Mountains. It grows with hardwoods, especially with oak trees.

- Cantharellus lateritius (Smooth Chanterelle) – this chanterelle species is quite different from its siblings. Instead of false gills, this species has a smooth undersurface or slightly wrinkled surface. This makes it easy to differentiate from other chanterelles. Smooth chanterelles grow with oaks and sometimes hickories.

Black Trumpets (Craterellus)

The black trumpet mushroom is another primary summer-to-fall species, but it isn’t unheard of to find it in late spring in the southeast. It’s not the prime season, so you probably won’t find huge patches, but they are definitely out there. Black trumpets can be hard to find since they blend right in with the forest floor, but with some practice, you can develop good “trumpet-hunting” eyes. These mushrooms grow around oaks and sometimes with other hardwoods, but oak trees are the best place to look.

Black trumpets have a unique vase or horn shape and are, as the name indicates, black all over. They do not have gills, and the cap underside is smooth or slightly wrinkled. They are a top edible species with a rich, smoky, earthy flavor that is unique to them. The fruiting bodies aren’t substantial, but the flavor is so robust that even a few are enough to add a new flavor profile to a dish.

Spring Is Investigation Time!

Spring is ideal for scoping out new mushroom foraging locations. A great technique for finding future foraging spots is to pay attention to the trees, not just the ones you are searching for morels around. Take note of large groups of old growth conifers, as they might have chanterelles around them later in the summer.

Before the leaf out and the underbrush grows out of control, closely observe your surroundings. It’s easier to see things in the woods now than it will be later on. For instance, I discovered an old chicken mushroom rotting on a log. Since I know they come back to the same spot every year, I marked that location down!

During chicken of the woods “season” I would never have seen this one because of all the underbrush and foliage. The lack of leaves and minimal underbrush is an opportunity to identify spots to look for other mushrooms later in summer or fall.

Mushroom Foraging Resources

If you’re new to mushroom foraging, here are some great guides to get started: How To Be A Successful Mushroom Forager, Mushroom Foraging 101, and Mushroom Identification Pictures and Examples.

This guide to the best identification books by region will help you find the best guides for you.

Curious about winter foraging in other areas? Check out our guides for across the US.

Leave a Reply