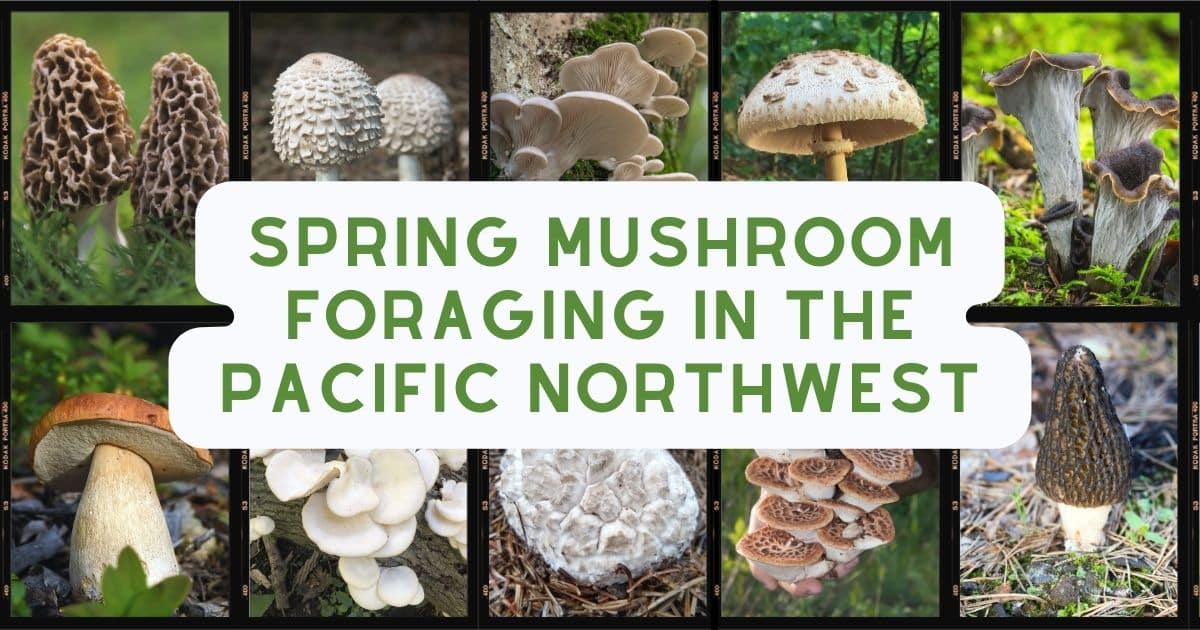

Spring in the Pacific Northwest brings warmer temperatures, less rain, and lots of delicious mushrooms. The top edible species that has everyone in the woods is morels—morel madness, you might call it. But in addition to morels, there are also some really wonderful edible species like oysters, puffballs, black trumpets, king boletes, and shaggy manes. Spring mushroom foraging in the Pacific Northwest requires patience, attentiveness, and dedication.

While there is a lot out there, many of these species are very specific about where and how they will grow, meaning you really have to search for them. Be prepared for long hikes, muddy trails, and adventure. The upside is that many of these species fruit in the same area every year, so once you find a patch, it’ll (hopefully) provide you with mushrooms for at least several years.

If I’m missing any Pacific Northwest spring mushrooms, please let me know in the comments! And check out the guides to Winter Mushroom Foraging in the Pacific Northwest, Summer Mushroom Foraging in the Pacific Northwest, and Fall Mushroom Foraging in the Pacific Northwest.

Jump to:

Top Eight Spring Mushrooms In The Pacific Northwest

Morels (Morchella)

The infamous and fought-over morel usually starts appearing in mid-late March. It starts out in lower elevations, where it’s warmer. Then, as the weather warms at higher elevations, it fruits there. Elevation extends the morel season sometimes into July, but the prime season for hunting them is April- May.

The beloved morel mushroom is a fungi treasure that only fruits in the spring. Unlike many other mushroom species, morels do not grow at any other time of the year. So, if you want to find morels, you must get out in the woods in April and May and dedicate some time to the hunt. Morels are extremely abundant in the Pacific Northwest, to the point that it is a huge commercial venture for many. One of the great things about morels is that they usually reappear in the same location year after year. So, once you find a spot, mark it well and visit it yearly to harvest.

The distinguishing characteristics of morel mushrooms include a cap with pits and ridges, a whitish stem, and a hollow interior. The size of morels differs significantly between species, but in general, they’re between 1-5 inches tall. The cap attaches to the stem in the middle or at the top of the inside of the cap.

Morels usually start showing up in the southeast before any other part of the country. Then, the season slowly progresses northwards as the upper states warm up. The Pacific Northwest can be its own beast sometimes, seemingly separate from the rest of the country climate-wise, but the appearance of morels is always a few weeks after the southeast sees them first. And, you know those finding them are absolutely posting on all the social media sites, celebrating their finds.

If you’re determined to find the elusive morel, I recommend keeping an eye on this progression so that you can hit the woods at the optimal time. Every year is different, some slower or later than others, and some earlier. It all depends on the winter weather, current climate, rainfall, and overall temperatures. Further down, you can see that even though the timing may vary, it has actually been pretty consistent over the last several years.

Many folks just start hitting the woods and checking their spots in early April, regardless of what is happening in the rest of the country. This works well, too, since that is historically the real start of the season. You can also pay attention to the weather and get yourself a soil thermometer. Morels usually start showing up when the daytime temperatures are above 50F, and nighttime temperatures are in the 40s. The ideal soil temperature is between 45-55F.

The Facebook Group Morel Mushroom Find Reports is an excellent and reliable resource. The Morel Sightings Map, which is updated annually, is another great way to see where people are finding morels.

To give you an idea of the difference over the last several years, here are the first Morel sightings in the Pacific Northwest as reported on the Morel Sightings Map.

- 2024 – mid-March

- 2023 – last week of March, but mostly April

- 2022 – last week of March, but mostly April

- 2021 – last week of March, but mostly April

- 2020 – intermittently during Feb, probably landscape morels. Other morels, last week in March, but mostly April.

- 2019 – mid-April

- 2018 – mid-March

An important point to consider when foraging morels (and any mushroom, really) is that elevation matters. This is especially true in the Pacific Northwest, where there are some pretty extreme elevation changes. Experienced foragers follow the morels up the mountains as the weather progressively warms on the mountaintops. This extends the season quite dramatically and can have you finding morels into June in cooler, higher-elevation areas.

When searching for morels in the Pacific Northwest, the best places to look are around oaks, white and Douglas fir, ponderosa pine, pacific madrones, and, of course, burn sites. The list below shows the range of habitat preferences depending on the species, but there is also a lot of overlap. In the Pacific Northwest, you may come across 12(!) different species of morels: two yellow morel species, nine black morel species, and one white morel species.

- Morchella americana – a yellow morel that grows with ash, elm, cottonwood, apple, and pear trees, among others. Looks gray when young, then develops yellowish brown ridges and pits.

- Morchella prava – a yellow morel that likes sandy locations, like rivers and lakes. Prefers oak trees and pines but will grow with other trees. Light yellow or white ridges and gray pits that make it look like a gray in general. Pits do turn yellowish with age.

- Morchella brunnea – a black morel that occurs in Oregon and likely across the northwest states. Grows with hardwoods, specifically oak and Pacific madrone. Sometimes fruits with conifers. Classic black morel with dark brown ridges and yellowish-brown pits.

- Morchella importuna – a black morel also known as the landscape morel, this species grows in landscaped areas like gardens, parks, and disturbed ground. Large species with dark brown ridges and yellowish-brown pits when mature. Early sightings of morels are usually of this species.

- Morchella rufobrunnea – this uncommon white morel is only known from coastal Mexico, california, and oregon. It is also a landscape morel, growing in gardens, planters, and along roadsides.

- Morchella snyderi– a black morel that prefers conifers, particularly white fir, Douglas fir, and ponderosa pine. Immature specimens look like yellow morels with yellowish-brown ridges. With age, ridges turn brown to black.

- Morchella frustrata – a black morel that grows with hardwoods and conifers, with a preference for Pacific madrone, ponderosa pine, sugar pine, Douglas fir, white fir, and oaks. Named “frustrata” because it stays yellow most of its life, even though it’s a black morel species.

- Morchella populiphila – a black morel that grows at river bottoms with black cottonwood. This is a half-free morel with a cap resembling a small beanie perched atop the stem.

- The burn-site morels – four species of black morels grow exclusively in burned-out conifer forests. They appear in the spring after a fire and often for several years afterward, too.

Spring King Bolete (Boletus rex-veris)

The Spring King mushroom shares many similarities with the highly prized King bolete mushroom (Boletus edulis). It has a mild, nutty flavor and a firm texture and is considered a highly desirable edible mushroom. If you like king boletes (aka porcini, ceps, penny buns, piggies), you do not want to miss out on Spring King season.

The spring king is a large bolete mushroom with a smooth, light to reddish brown cap. The pores on the underside of the cap are initially small and white, but as they age, they turn yellowish and green. The stem is thick and broader at the base, starting off cream-colored but gradually becoming brownish. Like most mushrooms in the Boletus genus, the upper portion of the stem has a white network pattern on its surface known as reticulation.

It can often be found growing in clusters, a rarity for the Boletus edulis species. Unlike some other boletes, it does not stain blue when cut, although the flesh of the cap may have a reddish hue. It typically fruits during spring in mountain conifer forests of the Cascades and Sierras. Its growth usually depends on snow melt and the occasional spring rain, which can prolong its fruiting season.

Oyster Mushrooms (Pleurotus)

The cool-weather-loving gray oyster mushrooms (Pleurotus ostreatus) have been fruiting all winter long, and as the seasons continue into spring, they will also continue growing. However, they may only hang out in early spring since they don’t like super warm weather. These are often a year-round species in areas of the Pacific Northwest, depending on the region and the climate conditions that year. But they are less common in the heat and humidity of summer. P. ostreatus is most likely encountered in the first couple of months of spring.

These oyster mushrooms have light brown caps, white to buff gills, and dense white flesh. They grow on deciduous hardwoods (trees that lose their leaves). Beech and aspen trees are common. Sometimes, they grow on conifers as well. Oyster mushrooms have a mild anise odor, meaning they smell a little sweet, like licorice. They tend to get bug-infested, so don’t wait to harvest them if you see them.

The aspen oyster mushroom, also known as the spring oyster, is a common springtime find. It fruits primarily on quaking aspen trees but can also grow on other aspen species and cottonwoods. Aspen oysters smell faintly of anise or might just have a subtle mushroom scent.

Veiled oyster mushrooms are generally winter mushrooms, but they might still be fruiting in early spring. They like cool to mild climates and grow on dead and dying hardwood trees. Veiled oyster mushrooms look different from other oyster mushrooms because they have a veil around the gills and usually grow alone instead of in dense clusters.

The Phoenix oyster mushroom is the opposite of the cooler-weather preferring gray oyster, aspen oyster, and veiled oyster. This one starts showing up as soon as the weather warms up, often from mid-April all the way through September. The gray oyster, P. Ostreatus, is more of a winter to early spring species, while the Phoenix oyster mushroom is a late spring to summer oyster mushroom species.

Black Trumpet (Craterellus)

Prime black trumpet season is over the winter, but they can still fruit in very early spring. Don’t stop looking for them throughout March. Black trumpets, also known as black chanterelles, are a sneaky species because they’re so hard to see. With their dark coloring and diminutive size, they tend to meld right into their surroundings; it takes some really careful searching to find them.

Luckily, though, black trumpet mushrooms usually grow in huge, spread-out groups, so if you’ve found one, you’ve found 100 (or more!). Black trumpets have a unique super umami flavor that makes them a real treat—there is nothing to compare it to because it is quite unique and wonderful.

Giant Puffballs

There are two primary large puffball species that show up at the end of spring, usually between May -June. Puffballs are beloved for their immense size, which is enough for quite a few meals. They don’t have a lot of flavor but quickly take on the flavor of anything they are cooked with.

Coming across one of these big puffballs is fun, even if you don’t want to forage them. They’re wacky; they look like someone actually sculpted each one into its unique and beautiful shape.

- Calbovista subsculpta (Sculpted Puffball) – softball-sized puffball with pyramid-shaped scales that give it a sculpted look. Grows with conifers from spring through fall. Differs from Calvatia sculpta (described next) by its scales, which are blunt, not pointed.

- Calvatia sculpta (Sculpted Puffball, also) — a softball–sized puffball with pyramid–shaped warts with tapered points. This species grows with conifers. It differs from Calbovista subsculpta listed above by the scales on the sculpted cap, which are pointy instead of blunt.

Prince Agaricus (Agaricus augustus)

The sweet marzipan-smelling Prince Agaricus is a great find if you can actually find it. Prince Agaricus is related to the button (i.e., portabello) mushroom but is much larger and has a dense, meaty texture. The marzipan-almond extract smell doesn’t stay with cooking, but it’s still a fantastic edible mushroom species. It’s also a great identification key when foraging—the prince has a lot of lookalikes, but none have the almond scent.

The Agaricus prince is a significant mushroom—very hard to miss. Young fruiting specimens look like whitish-tan tennis balls in the grass. In maturity, the caps can reach up to 14″ wide and are white with lots of dark brown scales. Prince caps are blockish instead of rounded like a button or portobello mushroom.

Prince agaricus mushrooms grow around conifer trees in disturbed areas – they like parks, forest edges, and roadsides. It’s rare to find this one in the forest; this is a suburban/urban foraging species. These mushrooms like warmth and rain and often fruit in the Pacific Northwest in May-June before it gets too hot. They actually usually fruit twice a year, in the spring and then again in the fall. So, if you find some springtime specimens, make sure to recheck the patch in the fall.

Shaggy Parasol (Chlorophyllum olivieri & Chlorophyllum brunneum)

A widely foraged species, the shaggy parasol should be approached with some caution. It has a toxic lookalike that looks A LOT like it but with a key difference. Make sure you understand how to tell these apart before foraging shaggy parasols.

Shaggy parasols are generally more of a fall mushroom, but they’ll also fruit in spring before it gets super hot (April-June). They grow in meadows, fields, lawns, and gardens, preferring open, disturbed spaces. They grow in dense groups, and it’s not uncommon for them to form fairy rings.

The shaggy parasol gets quite large, sometimes up to 8″ wide (that’s a dinner plate)! Its cap is white and covered with shaggy hair, almost like animal fur. On top of the white shag are brown scales scattered unevenly. It looks like a giant mushroom umbrella when the cap opens up to show its full breadth.

Dryad’s Saddle (Cerioporus squamosus)

This mushroom is much more common east of the Rocky Mountains, but it also shows up in the Pacific Northwest. It’s usually ignored as “not good enough” because old specimens are very tough and leathery. However, the odd-looking dryad’s saddle, also known as pheasant’s back polypore or hawk’s wing, is actually a delicious edible mushroom species. The key is to find it when it’s young, and then the texture is succulent, tender, and meaty. To dismiss it as “bad” would be like biting into a rotten apple and assuming all apples are gross. The key is to pick it at the right time.

The caps of the dryad’s saddle are beautifully decorated with dark brown brush strokes that make it look like a hawk’s wing or the feathers on a pheasant. The pore surface smells like watermelon rind or cucumber, a distinctive smell that sets it apart from other polypores. The dryad’s saddle has a unique crunchy texture and a more robust flavor than other mushrooms, making it a great addition to pickled dishes or those with bold flavors.

Spring Is Investigation Time!

While you’re out in the woods mushroom hunting, look around. Spring is the ideal time to scope out new mushroom hunting locations. There are clues out there that can help summer and fall foraging expeditions. You just need to be observant and pay attention to the trees.

Trees will tell you a lot, since many edible mushroom species have a preference for tree type. So, if you see large groups of old growth pines and firs, as they can guide you to boletes later in the season. Many boletes, like the king bolete, are prime edibles.

Before the underbrush grows completely out of control, take some time to closely observe the forest. Once that thick brush grows, it can be extremely difficult to see things (and get to them!). For instance, I discovered an old chicken mushroom rotting on a log in spring. Because I know they return to the same spot every year, I made sure to mark that spot!

During chicken of the woods “season” I most likely wouldn’t have seen this mushroom because of all the underbrush. In fact, I’m sure I passed by the spot several times in prime chicken season without ever seeing it. The short underbrush can be used to your advantage — as you hike, mark down any potential locations to investigate in summer or fall for other mushrooms.

Mushroom Foraging Resources

If you’re new to mushroom foraging, here are some great guides to get started: How To Be A Successful Mushroom Forager, Mushroom Foraging 101, and Mushroom Identification Pictures and Examples.

This guide to the best identification books by region will help you find the best guides for you.

Curious about spring foraging in other areas? Check out our guides for across the US.

KFrits says

Great info. Thanks so much!