Spring mushroom foraging in the Midwest is often fantastic but also erratic. So much depends on when the snow stops falling, and the soil and air temperatures warm up. Plus, spring rains make a huge difference. But, even though it can be unpredictable, there are some tremendous edible mushrooms out in the woods to find, including morels, chicken of the woods, oysters, and dryad’s saddle.

Springtime mushroom hunting in the Midwest generally begins in April and extends until mid-June. While there are numerous types of mushrooms and dried polypores in the woods to look at, the edible species are comparatively limited compared to the summer and fall seasons.

In the edible mushroom world, there is a spectrum of edibility to consider. Some species are highly sought-after edibles like morels and oysters. Others may still be edible but less tasty. There are also, of course, non-edible varieties due to toxins or texture. This guide is divided into two sections: highly desirable species and edible but not as desirable species. Sometimes, you only cross paths with the less desirable species, but bringing home a few springtime mushrooms for the table is still satisfying.

If I’m missing any Midwest spring mushrooms, please let me know in the comments! And check out the guides to Winter Mushroom Foraging in the Midwest, Summer Mushroom Foraging in the Midwest, and Fall Mushroom Foraging in the Midwest.

Jump to:

Top Seven Spring Mushrooms In The Midwest

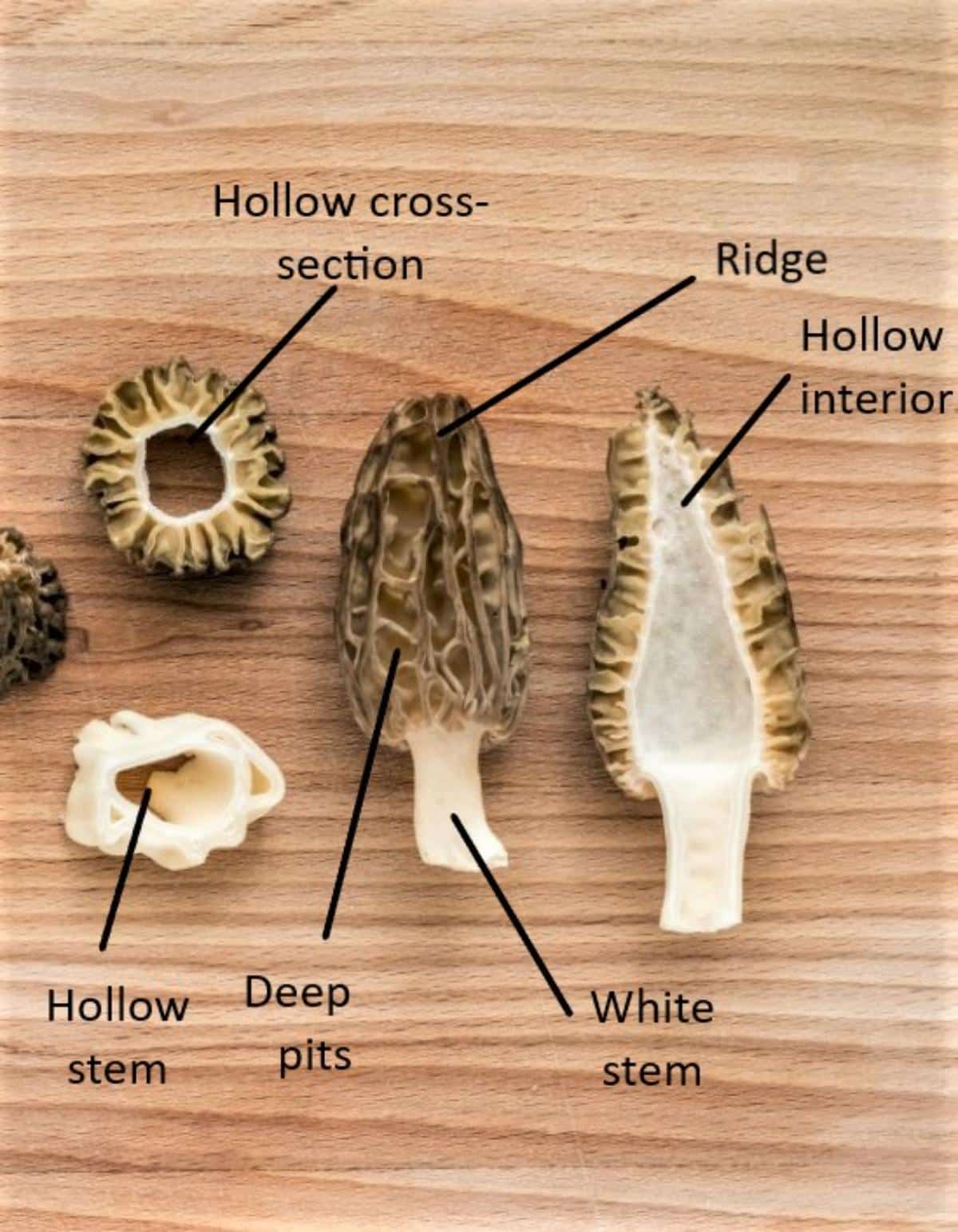

Morels (Morchella)

The highly adored and sometimes hard-to-find morel mushroom is a sought-after delicacy during spring. These mushrooms only grow during this time of year, so if you want to collect them, it is essential to start searching now.

Morels can be found mid-late March to May, depending on the region of the Midwest. They usually start fruiting in Ohio, Missouri, and Kansas in mid-March, then in the upper states a couple or few weeks after that. The season usually starts out slow, then picks up in April, and tapers off in May. Again, it all depends on where you live. Some more northern regions may only see fruitings in May and early June.

Morels start appearing in the south US states first, then pop up in the northern states a few weeks to a month later. By following southern foragers or groups, you can predict when they will most likely appear. The season starts in the warmer south, like Texas, the Carolinas, and Georgia. Then, it gradually moves northward as the weather gets warmer. To increase your chances of finding morels, keep track of this progress and plan your search accordingly.

It is a general belief that morels typically emerge when the lilacs start to bloom and serve as a reliable indicator of their spring appearance. However, this can be deceiving due to various factors such as weather, time of year, and the condition of lilac bushes. Relying solely on the blooming of lilacs may result in missing out on potential morel patches. It might be that the majority of morels only fruit later, but there is no way to know what could be missed by not searching earlier.

The Facebook Group Morel Mushroom Find Reports is an excellent and reliable resource. The Morel Sightings Map, which is updated annually, is another excellent way to see where people are finding morels.

To give you an idea of the difference, or actually, lack thereof, over the last several years, here are the first Morel sightings in the Midwest as reported on the Morel Sightings Map. As you can see, they’re pretty consistent but are subject to change.

- 2024 – mid-March (folks in KS and MO already reporting finds)

- 2023 – last week of March

- 2022 – last week of March

- 2021 – last week of March

- 2020 – last week of March

- 2019 – last week of March

- 2018 – last week of March

When searching for morels (and any type of mushroom), it is important to take elevation into consideration. Experienced foragers track the movement of morels up the mountains as the temperature gradually increases at higher elevations. This can significantly prolong the season and allow for morel sightings even in June in colder, higher-altitude regions.

The best places to search in the Midwest are around ash, elm, aspens, and cottonwood. Almost all the species will fruit with ash trees, so that’s an excellent all-inclusive starting point.

There are seven morel species in the Midwest. They don’t all have the same habitat, so you want to narrow your search based on what you’re looking for:

- Morchella americana – a yellow morel that grows with ash, elm, cottonwood, apple, and pear trees, among others. Looks gray when young, then develops yellowish brown ridges and pits.

- Morchella prava – a yellow morel that likes sandy locations, like rivers and lakes. Prefers oak trees and pines but will grow with other. Light yellow or white ridges and gray pits that make it look like a gray in general. Pits do turn yellowish with age.

- Morchella diminutiva – a yellow morel that prefers hardwoods like ash, hickory, and tulip. As the name suggests, this is a very small morel, rarely reaching 2.5-3″ tall. Pits are dark gray when young but turn brownish-yellow with age.

- Morchella cryptica – a yellow morel that is often called a gray morel because it is grayish when young. The ridges are white to pale yellow, and the pits are gray or dark brown. With age, the entire mushroom turns yellowish-brown overall. Very similar to Morchella americana and challenging to differentiate.

- Morchella angusticeps – a black morel that fruits around apple, cherry, tulip, and ash trees. It is tan or yellowish-brown when young but darkens to black with age.

- Morchella septentrionalis – black morel that grows with ash and big-toothed aspen. It is almost identical to Morchella angusticeps, except it is smaller and might be found growing out of decaying wood (an unusual trait for morels).

- Morchella punctipes – a half-free black morel with a cap smaller than other morels. It grows with hardwoods. The cap looks like a thimble setting atop a tall white stem.

Oyster Mushrooms (Pleurotus)

If the spring weather is mild enough, oyster mushrooms (Pleurotus ostreatus) will appear. These mushrooms have light brown to gray caps, white to buff gills, and dense white flesh. They are commonly found on deciduous hardwoods like beech and aspen but can also grow on conifers. Oyster mushrooms smell slightly of anise, so remember to smell them.

The aspen oyster mushroom is another oyster mushroom species that appears in spring. It is actually commonly called the spring oyster. As the name suggests, the aspen oyster grows primarily on quaking aspen trees. However, it will also fruit from other aspen species as well as cottonwoods. Like the gray oyster, it might have a slight anise scent or smell slightly mushroomy.

Yellow or golden oyster mushrooms also start showing up in spring and fruit through the summer. Golden oyster mushrooms are a non-native species spreading across the Midwest. They have been reported so far in Illinois, Iowa, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Wisconsin, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, and Delaware.

Yellow oysters escaped from cultivation and are now becoming more common in the woods. Forage these with abandon! These oyster mushrooms grow on hardwoods and seem to prefer elms. They are also found on oak, beech, and other hardwood species.

Dryad’s Saddle (Cerioporus squamosus)

The dryad’s saddle, aka pheasant’s back polypore, aka hawk’s wing, is often criticized for its tough texture. Many foragers ignore it because they think its toughness makes it inedible. However, the tough flesh only occurs with age. Young dryad’s saddle is a delicious spring edible mushroom; you just have to forage it at the right time. To dismiss it as “bad” would be like tasting a rotten apple from a tree and concluding that all apples are unpalatable. The key is to harvest them when they’re young and super tender.

With a distinctive dense texture and a bold flavor, the dryad’s saddle stands out from other mushrooms. It is ideal for pickling or incorporating into dishes with strong flavors. Or, just sauteed on its own with oil and garlic.

Wine Caps (Stropharia rugosoannulata)

Wine caps, which thrive in cooler temperatures, produce fruit during the spring and fall seasons. They can be found growing in wood chips and mulch, deriving nutrients from decomposing organic matter. These mushrooms have a deep red hue on their caps and can reach a significant size, similar to portabello mushrooms.

One distinguishing feature is the cog-wheel-shaped ring on their stem, while their gills start off pale gray and eventually turn to a dark purplish gray. Known for their robust texture and intense flavor, wine caps are a popular choice for dishes such as stuffed and baked, grilled, or used in risotto. Compared to store-bought button mushrooms, wine caps are definitely superior. While they can be found in the wild, they are also frequently cultivated as they are the most low-maintenance mushrooms to grow outdoors.

Chicken of The Woods (Laetiporus)

One of the best edible mushroom species, chicken of the woods, most often fruits in late summer to early fall. However, they will also show up whenever they want, including early spring. Chicken of the woods typically grows in large, overlapping clusters on decaying wood. As they mature, they become hard and too tough to eat (much like dryad’s saddle!), so it is crucial to inspect them before harvesting.

Despite not having the exact taste of chicken, chicken mushrooms have a texture reminiscent of chicken when cooked. They can be cooked in numerous ways and combined with a variety of flavors, including poaching, frying, sauteing, baking, mincing, and coating with breadcrumbs. They also pair well with BBQ spices and sauce, poultry seasoning, ginger and garlic, and marinade. The chicken mushroom’s flexibility makes it a great substitute for meat in vegetarian dishes.

Shaggy Manes (Coprinus comatus)

The tall, stately, shaggy mane usually fruits in fall but can also be found in spring. It’s less common during the spring, but you don’t want to miss this top edible species just because you’re not expecting it.

The shaggy mane mushroom is distinguishable by its long, cylindrical cap and unique characteristic of disintegrating into an inky black substance as it ages. Species in this Coprinoid family of fungi quickly break down into black goo as they age. Harvesting them in good condition is essential, as they can start decaying within a day. Storing these mushrooms is not an option.

Shaggy manes grow in open fields, grasslands, and meadows and do not grow on wood or logs. They are commonly seen along roadsides, trails, or areas where the ground has been disturbed and often grow in large, dense clusters. Their flavor is mild and delicate but can easily be overpowered by strong ingredients. Therefore, it is best to use them in simple recipes to fully appreciate their taste.

Wood Ears (Auricularia)

Wood ear mushrooms are found on wood and have an odd gelatinous consistency. One side of the mushrooms is covered with fine, fuzzy hairs, and they have an eerie resemblance to human ears. It’s actually pretty creepy how ear-like they look.

It is worth mentioning that not all brown jelly-like mushrooms are wood ears. It is important to be able to identify their lookalikes. Some lookalikes fall under the Exidia genus, such as amber jelly rolls, which are also edible but not so great. Although wood ears don’t have a strong taste, they offer a distinct texture when used in soups and stir-fries. They can also be dehydrated and easily rehydrated with water.

Three Edible But Not Prime Midwest Spring Mushrooms

Mica caps (Coprinellus micaceus)

Inky cap mushrooms aren’t a prime edible because they lack substance. They grow in massive fruitings, but it takes a lot of them to make a meal. Inky caps are more for adding flavor to something else than as a substantial mushroom meal. Do not eat these with alcohol! They contain a substance that makes them toxic when eaten with alcohol.

While inky caps are often abundant, they are also often covered with dirt. And, being part of the “inky” mushroom family, they will turn to liquid if not cooked quickly. These mushrooms cannot be stored; they must be used the same day they’re foraged.

The most commonly found types are the common inky cap and Mica cap, which typically emerge after heavy rainfall and have a short lifespan of 24-48 hours. For optimal taste, it is best to harvest young inky cap mushrooms that still have bell-shaped caps and undeveloped stems. They have a strong mushroom flavor that complements dishes such as risotto, quiche, and stews.

Deer Mushrooms (Pluteus cervinus)

Deer mushrooms are rather dull in appearance, and they aren’t very substantive. They are mostly gills with very little flesh. Deer mushrooms also have little flavor. These mushrooms are bland in looks and taste, but they are edible and prolific across the country in spring. In the Midwest, they’re one of the first mushrooms to appear after the winter snow has melted.

These mushrooms typically fruit on decaying wood, with a preference for hardwood, but they can also grow on conifers. They often look like they’re growing from the ground, but they actually are fruiting from buried wood.

Platterful Mushrooms (Megacollybia rodmani)

Similar to the deer mushroom, the platterful mushroom primarily consists of gills and has a very small amount of cap flesh despite its large size. These grey to olive-colored mushrooms typically grow on decaying hardwood and are most commonly found in late spring and early summer, following morel season.

These mushrooms are easily noticeable, with a potential cap width of up to 8 inches. They are large! Platterful mushrooms typically appear after heavy rainfall in May and June. However, it is important to be careful when gathering this species as there have been recent reports of them causing digestive problems. This mushroom has been foraged for a long time without any reports of toxicity, so the reactions were individual or possibly due to improper cooking. However, as a precaution, it is best to use caution when consuming these mushrooms.

Spring Is Investigation Time!

Spring is the ideal time to scope out new foraging locations and gather clues to predict or anticipate summer and fall foraging expeditions. It’s all about being observant and aware of your surroundings.

A helpful technique to anticipate the future of foraging is to pay attention to the trees, not just the ones you are searching for morels around. Take note of large groups of mature oak trees, as they can guide you to the location of oak-lovers like hen-of-the-woods.

Before the trees’ leaves fully appear and the underbrush grows, it is valuable to observe your surroundings — look around! You may spot things that will be hidden by foliage or underbrush later in the year. For instance, I discovered an old chicken mushroom rotting on a log. Knowing they return to the same spot yearly, I marked that spot to check later.

During chicken of the woods “season,” I would never have seen this one because of all the underbrush and foliage. Use the lack of leaves and minimal underbrush to your advantage and note any potential locations to look later in summer or fall for other mushroom species.

Mushroom Foraging Resources

If you’re new to mushroom foraging, here are some great guides to get started: How To Be A Successful Mushroom Forager, Mushroom Foraging 101, and Mushroom Identification Pictures and Examples.

This guide to the best identification books by region will help you find the best guides for you.

Curious about spring foraging in other areas? Check out our guides for across the US.

Roland Welsch says

Hunted morels, oysters, pheasant back and puffballs in WI for 55 years. Look forward to learning more.