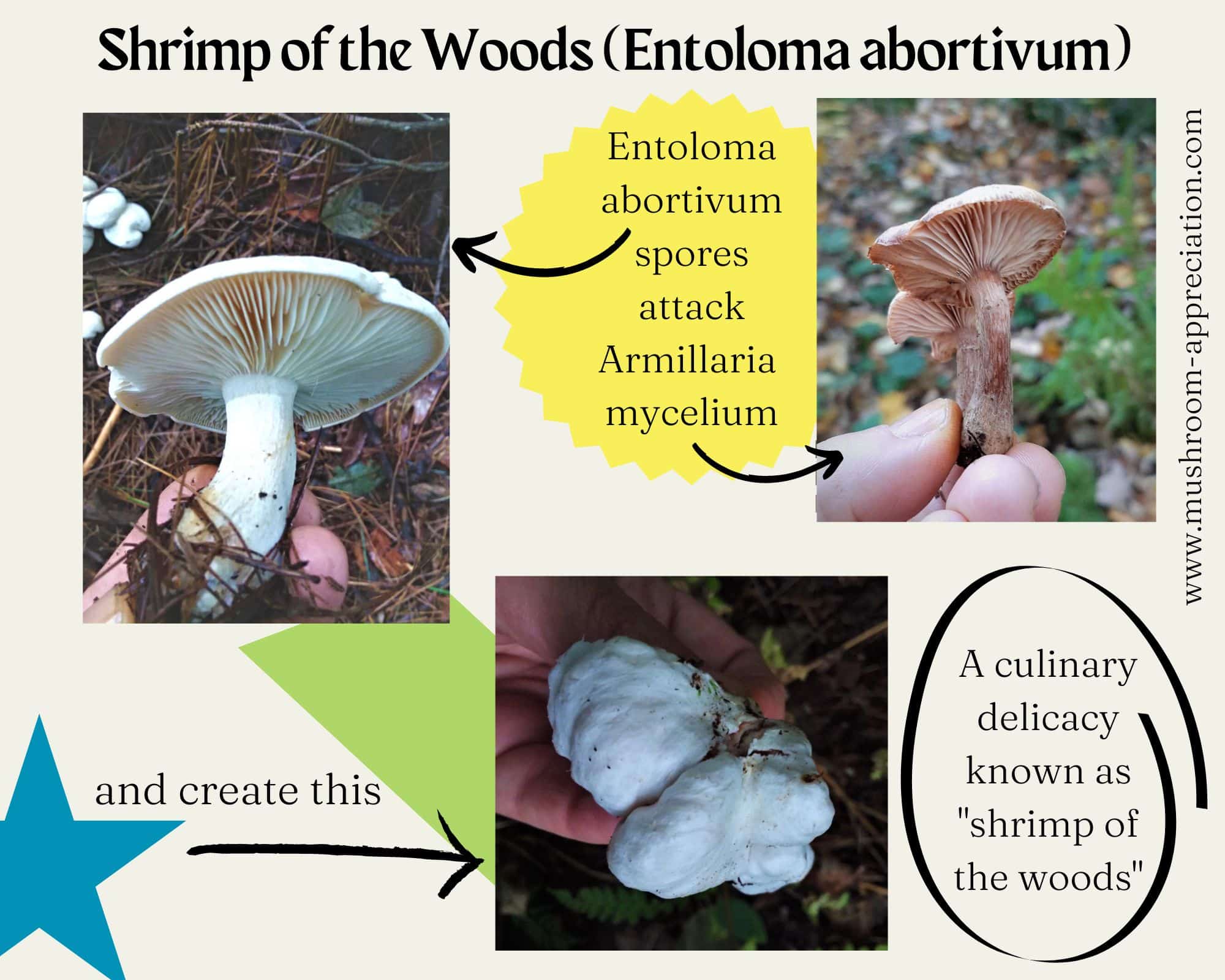

The shrimp of the woods (Entoloma abortivum) is a fascinating edible species most common east of the Rocky Mountains. The mushroom that foragers harvest is actually a combination of two species. Shrimp of the woods fungi parasitize the honey mushroom to form an odd, lumpy, white mass that is prized as a culinary treat.

Other common names for shrimp of the woods are Hunter’s Heart, Ground Prune, Aborting Entoloma, and Abortive Entoloma. In Mexico, it is known as Totlcoxcatl, which translates to “turkey wattle.” The name shrimp of the woods refers to the texture, which is rather shrimp-like. Some say it looks like a shrimp, too, but this forager doesn’t see that correlation.

Jump to:

All About Shrimp of the Woods

Describing shrimp of the woods as an edible species is a little complicated. It’s actually easy to identify, but understanding what you are foraging is more involved. Entoloma abortivum represents two significantly different-looking forms. In its “normal” mushroom form, it is a rather bland, unremarkable, grayish-gilled mushroom. It easily blends in with dozens of other species in the woods.

However, when Entoloma abortivum encounters another common, gilled mushroom, the honey mushroom, a bizarre transformation takes place. Entoloma abortivum infects the honey mushroom mycelium. Then, when the honey mushroom fruits, it comes out as a wildly distorted knobby white clump, looking nothing like a honey mushroom at all. This is the second form of the Entoloma.

This white bumpy, parasitized, and malformed honey mushroom is called shrimp of the woods, which is what foragers seek out in the woods. In guidebooks, you may find this species listed under Armillaria or Entoloma.

Shrimp of the woods has a long, misunderstood history. And it’s still not 100% clear. For over a hundred years, experts believed the lumpy white masses they found in the forest were Entoloma abortivum specimens that didn’t develop properly or were ” self-aborted” during growth. While foragers and mycologists noticed that Armillaria species were often nearby the aborted entolomas, they did not make a connection between the two.

A study in 1971 by Watling discovered there were Armillaria cells present in the tissue of the aborted Entoloma bodies. This led him to conclude that the Armillaria were parasitizing the Entoloma. To many mycologists, this was a plausible conclusion because Armillaria species are well known to be pathogens of other species.

For decades, this was the widely accepted explanation, even though there wasn’t any clear study verifying it. Then, a study done in 2001 determined that it was the exact opposite. The Entoloma was, in fact, the aggressor, and the Armillaria the victim. This study suggested that the lumpy white parasitized clumps should retain the aggressor’s name, Entoloma abortivum. Though, it might be more accurate to call it aborted Armillaria?

Now, after all this discussion, it is important to note that many foragers and experts report finding the aborted Entoloma specimens growing where there are no Armillaria species present. It could be that the honey mushroom mycelium is all underground, without any natural fruiting bodies visible. Regardless, this calls into question the exact relationship and what an Entoloma abortivum needs in order to unleash its parasitization nature.

In addition, Entoloma abortivum doesn’t just parasitize one species of Armillaria; it seems to be happy to parasitize a number of honey mushroom species. And, it seems to be opportunistic, infecting honey mushrooms when it has the chance but otherwise operating as a decomposer of decaying forest litter. That it can be adaptable and strategic is for sure an evolutionary tactic for this parasitic species. There still needs to be more study on this species, though, to fully understand how the two species interact and exactly how the parasitization works.

The gilled form and aborted forms of the Entoloma abortivum are both edible. Foraging the aborted form, the shrimp of the woods, is pretty easy as nothing else looks like it. The gilled version, though, needs to be gathered with caution. It resembles quite a few other Entoloma species, some of which are toxic or inedible. The unaborted form also isn’t regarded as much of a culinary delicacy, even though it is edible. Most people only forage the white, lumpy shrimp of the woods.

It’s not uncommon to find shrimp of the woods in mid-development or underdeveloped. It’s hard to say precisely what is happening, but the parasitized honey mushroom sometimes still manages to grow a stem or form gills. This means you’ll encounter specimens that are partially lumpy white round things while also featuring parts of the gilled Armillaria. The best guess is that the parasitization process was interrupted, or the Armillaria mycelium wasn’t fully infected.

The story of Entoloma abortivum is one of many demonstrating mycoparasitism, the phenomenon of one fungus parasitizing another fungus.

Shrimp of the Woods Identification Guide

Season

Late summer into fall. Entoloma abortivum, surprise, surprise, appears at the same time that honey mushrooms fruit.

Habitat

This species appears on decaying forest material, including leaf litter, stumps, and woody bits. It does not grow on live trees. Most often, it grows in clusters or scattered groupings, but sometimes it grows singularly as well. It’s not uncommon to find a considerable fruiting of them, presumably because the Entoloma parasite found lots of honey mushroom mycelium to infect.

Shrimp of the woods grows in hardwood forests. It fruits close to the ground or woody debris and is often hidden by leaf or forest debris.

Identification

To correctly identify shrimp of the woods, you need to know the unaborted and aborted forms of the species. It’s also helpful to know how to identify honey mushrooms.

Entoloma abortivum natural form:

The cap is gray to grayish brown, a steely gray usually, and smooth. It ranges from .75-3.25 inches wide and may be bald (no decorations) or be covered in very light fibers. The cap starts out hat-shaped, like a beanie, then expands outwards until it is flat. It may or may not have a raised bump in the center.

The gills are pale gray in youth, then turn pink. They are attached to the stem and commonly run down the stem a short way. The stem is .75-3.25 inches long and grayish-white, the same color as the cap. It may be slightly off-center, slightly enlarged at the base, and smooth, or have very fine hairs.

The flesh of the Entoloma abortivum is dense and white and does not change color when cut. It has a pink spore print. A key identification element is scent – this fungus smells like watermelon rind or grain meal, otherwise known as farinaceous.

As you can see, this form is not super interesting looking and can vary significantly in appearance. This, combined with its similarity to other Entoloma species, makes it challenging to identify on its own. If you see the shrimps along with the gilled mushrooms, then you know for sure.

Entoloma abortivum aborted form:

Entoloma’s aborted form looks like an oddly shaped puffball or a ball of fleshy popped popcorn. Or a head of garlic, still nicely intact and firm. Or a clump of white styrofoam packing peanuts jumbled together. It’s an odd-one, no matter which descriptive you use! The shrimp body is white or off-white, often with a pinkish tinge, and rounded and lumpy.

The body discolors tan or off-white when handled. There are no gills, no defined cap, and no stem. It is just a lumpy white globular-looking mass. The base often looks pinched. It ranges in size from .75-4 inches tall. Nothing else in the woods looks like this.

The inside is whitish or lightly pinkish, firm, and doesn’t change color when cut. The interior isn’t smooth or uniform; it is as lumpy and odd as the exterior. They are best foraged when they are still firm to the touch. Once they get super squishy, their quality is reduced.

The interior should also be white and not brown. It is old and not good to eat when it is brown.

Honey Mushrooms (Armillaria sp.)

There are approximately ten species of Armillaria in North America. They are widely known as honey mushrooms. The most commonly known species is Armillaria mellea. It was thought this was the primary species in North America, but it turns out it is not as common here.

Honey mushrooms aren’t the easiest to identify due to their many lookalikes. They are yellowish or brownish mushrooms (honey-colored) with 1-4 inch wide caps and a long whitish stem. Around the top of the stem is a whitish ring or skirt.

The gills of the honey mushroom are whitish and attached to the stem, sometimes running down the stem a little way. The flesh is white and sweet-smelling and does not change color when cup. The spore print is white – spore prints are a key identification point for these species.

Honey mushrooms are edible but should be foraged with caution because of the potential for confusion with lookalikes. Also, although this mushroom is considered a great culinary species in some countries, there is a potential for gastrointestinal distress if they’re not cooked properly. There are also reports that they will make you sick if you drink alcohol 12-24 hours before or after eating them.

Entoloma abortivum Lookalikes

Other Entoloma Species

Entoloma is a large genus of mushrooms with some poisonous members. There are around 1000 species worldwide, with approximately 22 in the US. In general, all the species are rather drab looking, grow on the ground, and have pink or pinkish gills and pink spore prints.

Amanita “Eggs”

Amanita species start out as white egg-like sacs that look superficially like shrimp of the woods. They are easy to differentiate when you cut them open. Inside the Amanita sac is the outline of gills and stipe that are forming. Many Amanita species are poisonous, and some are even deadly, so be careful with this one!

Puffballs

Puffballs are round and whitish-colored with a soft marshmallowy interior. Like with Amanitas, the way to be sure of your find is to cut the mushroom open. Remember, shrimp of the woods interior is lumpy and firm, not soft and spongy.

Foraging Shrimp of the Woods

Because the Entoloma in its gilled form can be confused with many other species, it’s best only to forage them when you see the malformed ones nearby. When you see the white, lumpy fruitbodies on the ground, you can be pretty sure the gilled grayish mushrooms beside them are the gilled Entoloma abortivum. However, you should still double-check your identification in case a different Entoloma just happens to be fruiting right there.

Unfortunately, insects adore shrimp of the woods as much as the mushroom forager. This means finding nice specimens that aren’t bug-ridden can be challenging. Give the shrimp a little squeeze before picking; if it’s soggy or bugs fly around it, leave it be. It’s too far gone at that point. When you squeeze it, it should still be firm and feel dense. This is good eating shrimps.

Don’t forage any specimens for the table that are brown inside or mushy. The interiors should be whitish or pinkish and pretty firm. Inside will always be a bit pithy, not a completely firm interior, but it shouldn’t be spongy.

The fruiting bodies shouldn’t be cracked or split, either, as that is a sign the mushroom is past maturity or getting there. Ideal specimens look look a firm, still together, well-rounded head of garlic.

Cooking With Shrimp of the Woods

**Special Note: Shrimp of the woods is known to be one of the wild fungi that people tend to have sensitivities too. Many people eat it without any issues while others experience gastric distress. You should always eat just a small amount of any wild mushroom the first time, just to be sure you can tolerate it. This is especially important with shrimp of the woods, which seems to high up on the species

Shrimp of the woods fungus has a texture like shrimp, firm, yet not overly dense, with a bit of crunch or snap. The mushrooms hold their shape during cooking and, when fried, can easily be mistaken for popcorn shrimp.

Their flavor is relatively mild (just like ocean shrimp) and does well combined with strong flavors, especially spices. The lumpy popcorn-like lumps absorb a lot of water, so whichever cooking method you use, make sure you cook the excess moisture out of them, or else they’ll be watery tasting and bland. If you harvest them after a heavy rain, be prepared to squeeze a lot of water out.

Foraged shrimp of the woods have a lot of crevices and tend to collect dirt and debris. Brush them off well and cut off any extra dirty parts. Soaking in water is not that effective; usually, all it does is water-log the mushroom without getting a lot of dirt out.

Shrimp of the woods recipes:

- General Tso’s Shrimp (of the woods)

- Oven Fried Shrimp of the woods

- Honee Garlic Shrimp of the woods

- Lobster and shrimp mushroom bisque

- Fried Popcorn Shrimp of the woods (TikTok)

Shrimp of the Woods Common Questions

Is shrimp of the woods the same as the shrimp mushroom?

No, they are two different mushrooms, but share a common name, hence the muddling of identification. The “shrimp mushroom” is Russula xerampelina (and related species) and gets its name because it smells like shrimp. “Shrimp of the woods,” which this article is about, gets its name from its texture similarity to shrimp. The Russula is a red or dark brown-capped gilled mushroom, so it is easy to differentiate from the lumpy, white shrimp of the woods.

This naming situation is common, and one that happens a lot among mushroom species because popular names overlap. When people associate mushrooms with something else, i.e. shrimp or chicken or oysters, there becomes a huge space for jumbling of species.

Because of this confusion, a lot of people insist on only using the scientific names because they are clearer and obviously indicate the exact species being referred to. This forager appreciates that sentiment, but finds it elitist because there are huge numbers of foragers currently and from generations past that didn’t and don’t have strong formal educations. Afterall, foraging was considered a thing for the poor, unfortunates who needed to forage for sustenance (in North America).

It is extremely helpful to know the scientific names, but it should by no means be used as a gate to keep people out of foraging or identification. Instead, we work with what we have, which is often confusing, and try to find ways to improve through education but being careful not to be exclusionary.

Now we know there are two mushrooms with shrimp in their name, two species that look vastly different, and so we can easily use physical characteristics to tell them apart.

Ellen says

Thank you. An excellent and thorough description. I really appreciate the extra photos and comparisons. Yikes, I think some of the ones I cooked last night were a bit too far gone.

Jenny says

Oh, I hope for your sake they weren’t too far gone!! That’s not a fun time. Glad the guide helped!!

Karl Hillig says

I’ve found Shrimp of the Woods at the base the 150 year old sugar maples in my yard, that have been inexplicably dying off. The presence of Armillaria mycelia in the soil may explain the demise of these majestic giants. So sad…. I wonder if Entoloma is at least providing some protection to the remaining trees?

So happy to have found your blog! Thank you for sharing!

Trina Patterson says

Where can you buy them from? I li e in nc

Jenny says

They only grow in the wild, so you have to know a forager or learn how to hunt them yourself.