The rusty gilled polypore, scientifically known as Gloeophyllum sepiarium, is an attractive and common species of wood decay fungi. It likes to grow from wooden structures, like porches, decks, and other treated lumber, as well as from decomposing deadwood. Due to its propensity to grow on lumber, it is a commonly encountered fungus. The rusty-gilled polypore is a prime example of nature’s vast adaptability and fungi’s complex ecological roles.

- Scientific Name: Gloeophyllum sepiarium

- Common Names: Rusty gilled polypore, conifer mazegill, yellow-red gill polypore

- Habitat: Dead conifer wood, sometimes hardwood

- Edibility: Inedible, not toxic

Jump to:

All About The Rusty Gilled Polypore

This fungus is known by the common names of conifer mazegill, rusty-gilled polypore, and yellow-red gill polypore, each of which speaks to some defining characteristic of the species. It is known for its distinctive feature of having gills instead of the typical pores found in polypores.

The rusty gilled polypore’s scientific name, Gloeophyllum sepiarium, is derived from Greek and Latin. “Gloeophyllum” means “with sticky leaves,” a reference to the mushroom’s gilled structure. “Sepiarium” translates to “dark or sepia-colored,” hinting at its distinctive coloration.

The species has been recognized and reclassified by various authorities over the years, resulting in a range of synonyms. Some of these include Agaricus asserculorum, Agaricus boletiformis, Agaricus sepiarius, and Lenzites sepiaria among others. However, the accepted binomial name remains Gloeophyllum sepiarium.

Identifying the Rusty Gilled Polypore

Season

This mushroom is an annual or reviving species, meaning it lives for just one year or acts more like a perennial. This usually depends on location and climate. It appears most prolifically during the late summer and fall seasons. In warmer climates, it may even persist over winter. It is widely distributed across North America and can also be found in other parts of the Northern Hemisphere.

Habitat

The rusty-gilled polypore is a saprobic species, meaning it obtains nutrients by decomposing dead or decaying organic material. This fungus causes a brown rot, breaking down the cellulose in the wood while leaving the lignin behind. It is commonly encountered in wooded areas but can also be found on lumber in urban settings. It is most commonly found on dead conifer wood, making its home on logs and stumps. Although it has a preference for conifers, it can occasionally be found on hardwoods in conifer-dominated ecosystems.

It might appear individually or in dense numbers on the wood.

Identification

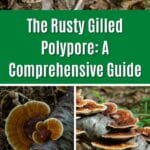

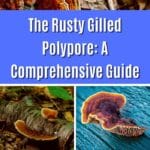

Cap

The cap ranges in size from 0.8-6 inches wide. It is loosely bracket or fan-shaped and has a texture that transitions from velvety in its youthful phase to smooth as it matures. The coloring is frequently distinctively concentric, with zones of color and texture.

When young, the cap is yellow to orange, but it gradually turns yellow-brown to dark brown with age. It is often nearly black towards the point of attachment to the wood. The outer edge usually retains its yellow or orange hue.

Gills

Unlike the pores commonly found in polypores, the rusty-gilled polypore features irregular and often fusing gills. These are quite close and often mixed with slot-like pores, giving it a maze-like appearance. The gills are creamy or pale brown when young with yellow-brown edges; they become darker brown with age.

Stem

The rusty-gilled polypore lacks a stem, a common characteristic of many polypores. The fruiting body is primarily composed of the cap and the gills.

Flesh

The flesh of the rusty gilled polypore is dark rusty brown or dark yellow-brown with a corky texture.

Odor and Taste

The mushroom has a mild odor and taste.

Spore Print

The rusty gilled polypore produces a white spore print.

Rusty Gilled Polypore Lookalikes

Oak Mazegill (Daedalea quercina)

The oak mazegill is similar in appearance but grows on oaks and has a lighter colored cap.

Gilled Polypore (Lenzites betulina)

The gilled polypore or birch mazegill has white gills and typically grows on hardwoods. It is lighter colored, but also has the concentric color zones which can make it easy to confuse with older, “washed out” rusty gilled polypores. Pay attention to cap and gills coloring as well as tree host to be sure.

Turkey Tail (Trametes versicolor)

Turkey tail is superficially similar from a top view but lacks the distinctive gills of the rusty-gilled polypore. Turkey tail fungi have white pores on their underside.

Porodaedalea pini

This species is one of the largest fungal killers of conifer trees. Like the rusty gilled polypore, this fungus also features a brown spore print and a hard, thick, rough cap. However, it tends to grow on live trees, setting it apart from the rusty gilled polypore. It also has pores, not gills, which easily differentiates it from the rusty gilled polypore.

Culinary Uses of the Rusty Gilled Polypore

While the rusty gilled polypore is not considered edible due to its tough, corky texture, it is important to note that “inedible” does not necessarily mean “toxic.” Always remember to correctly identify any mushroom before consumption and avoid eating any mushroom you are unsure about.

Rusty Gilled Polypore Medicinal and Environmental Properties

The rusty gilled polypore, like many fungi, is being studied for potential medicinal uses. Research has indicated that it may possess antioxidant and anti-cancer properties. Moreover, it has demonstrated effectiveness as a bioremediation tool, showing the ability to remove significant amounts of chromium from the soil.

Common Questions About the Rusty Gilled Polypore

Is rusty gilled polypore edible?

It is not edible due to it’s corky, leathery texture. However, it’s not poisonous either.

Leave a Reply