The orange crep mushroom really stands in the forest due to its distinctive orange gills and fuzzy cap. This species is not edible but is a neat find. It grows across North America and is very common. It is likely the most common Crepidotus species in the country. It also grows widely around the world.

This mushroom is sometimes confused with edible oyster mushrooms by beginner foragers. It’s actually pretty easy to differentiate once you know the key identification points. Sadly, the orange crep disappoints many a forager out for edible species.

- Scientific Name: Crepidotus crocophyllus

- Common Names: Orange crep, Saffron oysterling, Saffron crep

- Habitat: Dead and dying hardwood logs

- Edibility: Inedible

Crepidotus crocophyllus by Jess Evans on Mushroom Observer

Crepidotus crocophyllus by Jade on Mushroom Observer

Jump to:

All About Orange Crep Mushroom

The orange crep mushroom belongs to the genus Crepidotus. The name is from Latin and means “cracked ear.” The name “crocophyllus” means “saffron colored leaves (gills),” which perfectly describes its distinctive gill coloration. Most Crepidotus species are tan or whitish and rather bland looking. The orange crep is distinctive within the family simply for its coloring. The Crepidotaceae family has more than 320 varieties worldwide.

Agaricus crocophyllus, Crepidotus dorsalis, Crepidotus fulvifibrillosus, Crepidotus appalachiensis, Crepidotus aureifolius, Crepidotus distortus, Crepidotus nephrodes, Crepidotus subaureifolius, and Crepidotus subnidulans are all synonyms.

Crepidotus crocophyllus by Huafang on Mushroom Observer

Orange Crep Identification

Season

These mushrooms appear from July through September in most areas. It is a fall to mid-winter species in California and the Pacific Northwest.

Habitat

The orange crep loves decaying hardwoods but occasionally shows up on conifer logs. This mushroom grows from wood; it never grows from the ground. Look for them on fallen logs. This mushroom may grow alone or in scattered groupings. It also commonly grows in dense groups with overlapping specimens.

Orange creps, and Crepidotus species in general, are known for their hardiness. They often fruit strongly when no other mushrooms find the climate suitable. This is actually odd because they grow on very old, rotting logs that dry out quickly. Yet, they find the nutrients and moisture needed to emerge during even the driest times. That’s some tough mycelium!

Crepidotus crocophyllus by Crystal on Mushroom Observer

Crepidotus crocophyllus by Geoff Balme on Mushroom Observer

Identification

Cap

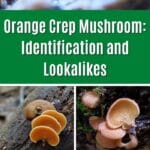

An orange crep’s cap typically measures between 1/4 to 1/2 inch across. The cap is semicircular, fan, or shell-like, just like an oyster shell. The edges of the cap roll under a little bit, especially when the mushroom is young. The cap is very thin and delicate.

The cap is covered with thin orange-brown to reddish-brown fibers that sometimes combine into small scales. Under these fibers, the cap’s base color varies from whitish to dull brownish or yellowish.

There is actually a lot of variance in cap color and orange-brown fiber appearance with this mushroom. It may be very white, with just a few fibers scattered across it. Or, it can be so covered in thin orange-brown fibers that it looks entirely brown.

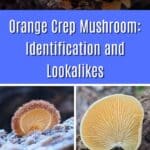

Gills

The gills of young specimens are pale pastel orange to darker orange. They mature into a dull brown. The gills form a tight pattern and radiate outward from the wood attachment point.

The gill coloring, like the cap, can vary widely. The species is known for its bright orange gills, and often, they are a very deep and beautiful orange. However, they can also be so pale orange that they look more white than orange. Then, as the mushroom ages, the brown spores release over the gills and turn them brown.

Stem

The orange crep lacks a traditional stem. A short, hairy plug of tissue attaches it directly to the wood substrate.

Flesh and Staining

The flesh is soft, thin, and whitish. It keeps its color after cutting.

Odor and Taste

This mushroom lacks any notable smell. It has a bitter or neutral taste.

Spore Print

The spore print is brown.

Crepidotus crocophyllus by Debbie Klein on Mushroom Observer

Crepidotus crocophyllus by Jarod Albrecht on Mushroom Observer

Crepidotus crocophyllus by Derek Ziomber on Mushroom Observer

Crepidotus crocophyllus by Chris Cassidy on Mushroom Observer

Crepidotus crocophyllus by Liz Popich on Mushroom Observer

Orange Crep Mushroom Lookalikes

Peeling Oysterling (Crepidotus mollis)

This relative to the orange crep mushroom has the same shell shape and growth pattern. It is much plainer looking, though, with a tannish cap and whitish gills. The peeling oysterling also has a rubbery cap that is smooth, without fibers or any other decorations.

Flat Oysterling (Crepidotus applanatus)

The flat oysterling, as the common names suggests, has a flattened cap. It is still shell-shaped, but instead of having strongly inrolled edges and a slightly incurved look, it is mostly flat. It also differs from the orange crep in cap and gill coloring. The flat oysterling is brownish to whitish, a bit drap overall, and no hints of orange.

Scaly Oysterling (Crepidotus calolepis)

This lookalike is tricky. The scaly oysterling is small, shell-shaped, grows on wood, and has lots of thin brown fibers covering the cap. From above, it look a lot like the orange crep mushroom. The primary difference is the gills. This can be tricky too, though, if the orange crep specimen has lightly colored gills. Also, they both have brown spores which turn their gills brown with age. So, if you find an older specimen, the gills could be the same brownish coloring.

The gills on the scaly oysterling are white when young and never orangish or yellowish like the orange crep. Even though the orange crep might have pale orange gills that look whitish, you can usually see some sort of coloring. Another key difference is texture. The scaly oysterling cap is rubbery and the orange crep’s is not.

Oyster Mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus)

The orange crep looks passingly like an oyster mushroom because of its shell-shaped cap. They also both grow on dead and dying trees and fallen logs. And, when the orange crep is more bland looking, its tannish cap or whitish gills can be confusing.

But there are many differences that make it easy to tell them apart. Oyster mushrooms are grayish, tannish, or whitish – they are never orange. Another key difference is size. Oyster mushrooms are much bigger. Orange creps are a small mushroom. Of course, beginners might think they are just baby oysters waiting to grow up, but this is not the case. Baby oyster mushrooms are never this small – even when young, they are thicker, denser, and broader.

A final difference is smell. Most oyster mushrooms have a distinct anise scent. Orange crep mushrooms don’t have any smell. If you have any questions about which mushroom you’ve found, do a spore print. Oyster mushrooms have white spore prints; orange creps have brown spore prints.

Mock Oyster (Phyllotopsis nidulans)

The mock oyster mushroom is also similar in color and fuzziness. It has a bright orange cap covered in fibers and orange gills. It is also small and the same oyster-shell-shape as the orange crep. There are three big differences. The mock oyster has a strong, unpleasant, skunky smell (although the odor can sometimes be absent). The fibers on the mock oyster’s cap are white, not brown. And, the mock oyster has a pinkish spore print. So if you’re in doubt, do a spore print.

Orange Crep Mushroom Culinary and Medicinal Uses

The orange crep isn’t edible, although it isn’t known to be poisonous either. They’re just too small and thin to be worth collecting. Their texture and minimal meat don’t make them practical for the kitchen.

There are no known medicinal properties.

Crepidotus crocophyllus by Andrew S on Mushroom Observer

Orange Crep Mushroom Common Questions

What are the key identifying features of the orange crep mushroom?

The orange crep (Crepidotus crocophyllus) is characterized by its small size (1/4 to 1/2 inch wide), semicircular or shell-shaped cap covered in brown fibrils, and striking pale to dark orange gills in young specimens. It lacks a traditional stem and grows directly on decaying hardwood.

When and where can I find orange crep mushrooms?

When and where can I find orange crep mushrooms? Orange crep mushrooms typically fruit from July through September. They are commonly found in deciduous woods, particularly on fallen logs, dead branches, and stumps in well-shaded, damp areas. While they prefer hardwoods, they may occasionally grow on conifer logs.

Are orange crep mushrooms edible?

While orange crep mushrooms are not known to be toxic, they are generally considered inedible due to their small size and thin flesh. Their culinary properties have not been extensively studied, and they are not typically harvested for consumption.

Leave a Reply