Oh, the elusive King! When you are blessed with fresh, young un-insect-inhabited King Boletes, you will feel like you won the lottery. The king bolete (Boletus edulis) is a majestic edible mushroom, with unequaled flavor and texture. But, this isn’t a king who makes it easy to be found.

Hunting king boletes takes patience, practice, and quite a bit of good fortune. It isn’t just that they are tricky to find; it’s also that every other animal and insect and slug in the woods is searching them out too. King boletes are beloved by all!

In Europe, these boletes are called porcini or ceps or penny buns. In North America, we call them all these things too, but mostly we like the name “the king.” Every region has it’s own special name for this prized fungi. Here are some excellent cooking and recipes ideas.

As with most fungi in North America, the king bolete taxonomy is complicated and understudied. All mushrooms that look like the European Boletus edulis are still mostly classified under that name. North American mycologists have differentiated a few species, but most get put under the umbrella name Boletus cf. edulis.

This cf. classification simply means “compare to” Boletus edulis. In other words, yeah, it probably is a species related to Boletus edulis but we don’t know for sure. For the forager looking for an amazing edible mushroom, though, this is fine.

All king boletes and the related species have similar identification points, meaning you can forage this mushroom without worry. There are no poisonous lookalikes; but, you do have to pay close attention to all the distinguishing features.

In this guide, we will cover all the edulis and edulis-like species that North American foragers hunt. If you find a bolete that matches this description, but seems a little different, record it. It might be an undocumented type needing classification and a name.

Jump to:

All About King Boletes

King boletes are mycorrhizal; this means they form mutually beneficial relationships with specific trees. The tree and fungus connect underground and share nutrients, resources, and feedback about the environment. Some boletes assist their trees with disease resistance or by reducing environmental stress.

The king bolete only grows on the ground. It does not grow on trees, logs, or wood. The various edulis boletes all have tree preferences. This is important to know, and very helpful when it comes to foraging. It means you can target certain tree growths during specific times of the year for better foraging success. It’s not a for-sure method, of course, but a great head-start in hunting these elusive gems.

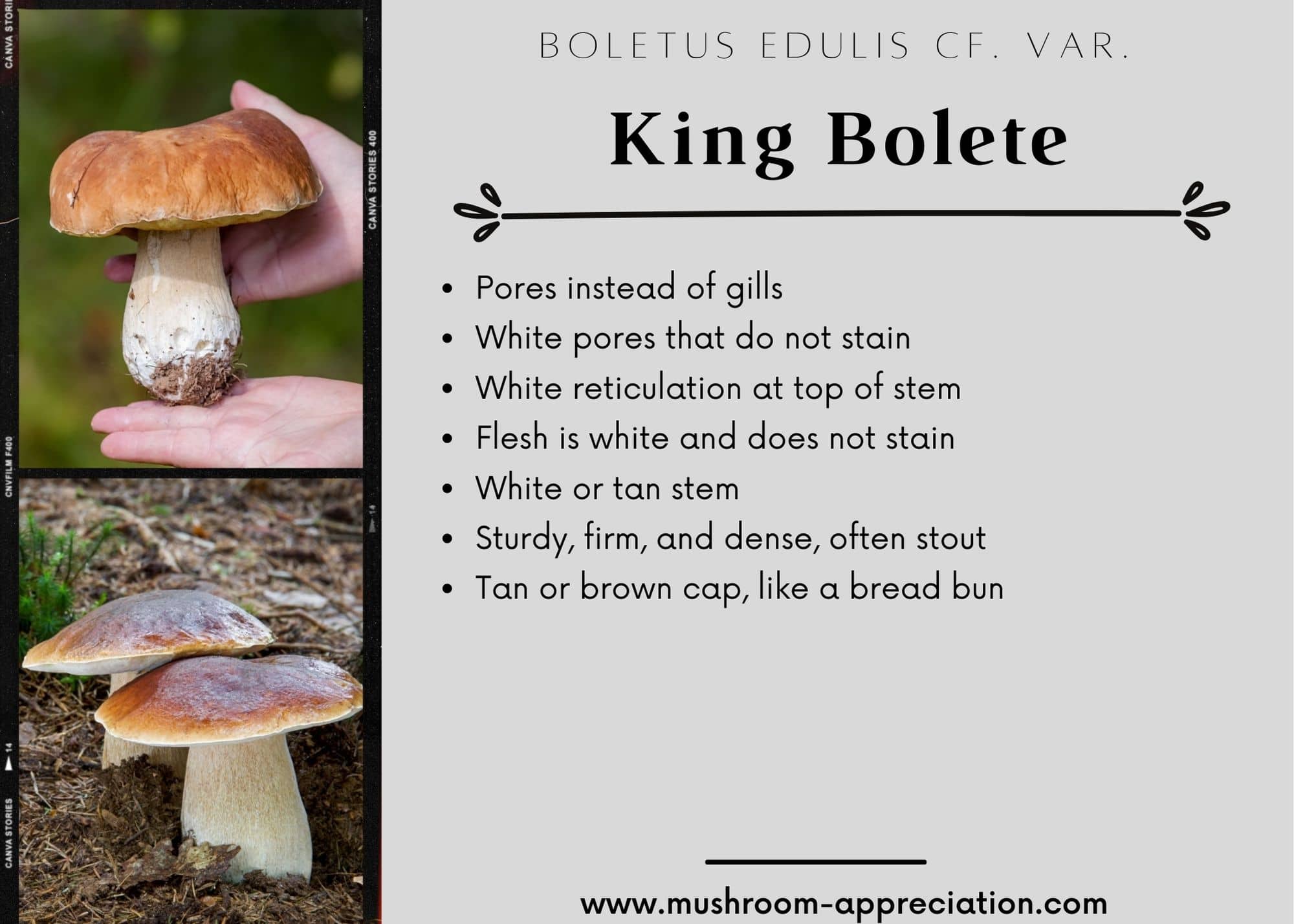

King boletes are large mushrooms with a tannish brown bread bun-like cap and thick and chunky white stem. The king bolete scent is distinctive too, a bit like sourdough. So, not only do they look like bread buns on the forest floor, they also smell like it!

These boletes are thick, dense, mushrooms with a nutty, meaty flavor and smooth, creamy texture after cooking. One reason it is so beloved is because it’s incredible denseness makes it quite a meal. The flesh gets tender in cooking and doesn’t disintegrate like some other mushrooms. Everywhere they grow, they are considered the choicest of edible mushrooms.

King boletes can get really big – a mature specimen easily weighs 1-2 lbs. In 1995, a huge porcini was found in Scotland. It’s cap was 16 ½ inches wide and it weighted 7 lbs! In 2013, one of similar size was discovered in Poland and made international news.

The king bolete is a food source for banana slugs, red squirrels, deer, mice, and a host of insects. To successfully forage king boletes, you must be faster than these creatures – it’s a fight worth taking on. But, you should always leave some for the forest dwellers – that’s just good manners and it helps spread spores to new places and possibly create more king bolete patches.

Where Do King Boletes Grow?

King boletes grow worldwide, though not naturally in the Southern Hemisphere. They are an introduced species to Australia, Brazil, and South America. In Europe, Asia, and North America, king boletes are endemic and a highly prized edible.

North American species, like many mushrooms on the continent, grow on either the east coast or west coast. The Rocky Mountains seem to be a big divide that many fungi species don’t cross.

What Are Bolete Mushrooms?

There are over 300 species of Bolete and the one distinguishing feature that they all share is that they are fungi without gills; instead, they have hymenial pores. This translates to a smooth cap underside where the gills of other mushrooms are.

The pores under the cap are actually thousands of very skinny, short tubes, holding the fungi spores. These tubes are packed together so tightly, that you usually can’t make them out individually.

When a bolete is young, the pore surface is hard, like the surface of a brand new sponge. It’s hasn’t absorbed moisture yet, but you know it will in great quantity given the opportunity. Older boletes pore surface is like a wet or old, used sponge –very squishy, soft, and often discolored and a little unsightly.

Boletes are renowned for maturing badly – they go from firm and dense to soft, squishy, bug-ridden, and moldy very quickly! Good rains prompt them to emerge, then any rains after that intensify their decline to old and gross looking.

This quick life-span makes identification interesting, to say the least. A young bolete specimen often looks extremely different from it’s mature companion – any time you study boletes you want to learn what the young and mature fruits look like for each species.

The majority of boletes are mycorrhizal, forming mutualistic relationships with trees and plants. In many cases, the bolete species is specific to the tree species. For example, the birch bolete which only grows with birch trees. To identify a bolete, you often need to identify the tree host.

North American King Bolete Species

King Bolete (Boletus edulis)

The primary species of king bolete, and the type-species, is Boletus edulis. It is reported that this species grows across North America, but as we mentioned previously, this preciseness of this is still a bit unknown. This is the mushroom in Europe that is known as ceps, porcini, piggies, or penny buns.

King boletes associate primarily with spruce or pine trees. In California, they’re found around Bishop pine and Monterey pine. They emerge in late summer to early autumn after significant rains. Caps of king boletes are large, 3-12 inches wide and sticky to the touch. They are light brown to dark brown or reddish-brown. As they age, the caps get darker.

The stem of the king bolete is significant – thick, bulbous, and large compared to the cap. King bolete stems are white, 3-10 inches long, and up to 3 inches thick. It bulges in the middle to create a club-like shape. The overall appearance is thick, squatty, stocky, or stout.

Under the cap, at the very top of the stem is fine white and very abundant reticulation. This is a key identification feature. The pores under the cap are white when young but turn yellow and then brown as the mushroom ages.

King bolete flesh is white and it does not change color when cut. The cap and stems don’t usually bruise, but might turn a very light red or brown.

- Light brown to dark brown cap

- Tacky cap surface when wet

- White stocky stem

- Pores, not gills

- Pores white when young, yellow then brown as it matures

- White flesh doesn’t change color

- Cap and stem don’t bruise, or bruise very lightly red or brown

- White reticulation at the top of the stem where it meets the cap

East Coast

Stout King Bolete (Boletus variipes)

This bolete is closely related to Boletus edulis and looks quite similar. The primary differences are cap consistency and growth habitat.

Boletus variipes cap starts of buff brown or tan, than becomes darker brown or gray with age. The caps are 2-8 inches wide and often are covered with cracks or fissures, especially as they mature and in hot weather. Caps are velvety and dry when young, unlike the tacky surface of B. edulis.

The stems of B. variipes are 3-6 inches long, white or light brown, and very thick. These stems are swollen in the middle, and often they are much thicker at the bottom than at the top. This gives them an especially squatty appearance. At the top of the stem, where it meets the cap, there is fine white or brownish reticulation.

Under the cap, the pores are white when B. variipes is young. They turn yellow or olive as they age, and they do not bruise when handled. The cap and stem do not bruise, either. This bolete’s flesh is white and doesn’t stain when cut.

B. variipes emerges in late summer to fall in eastern North America. It primarily associates with oaks, but can be found with other hardwoods like aspen, beech, and maple.

- Buff, tan, or brown caps

- Caps patchy or cracked with age or heat

- White or light brown swollen stem, often thinner at top

- Pores white when young, turn to yellow or olive

- White flesh does not change color

- Cap and stem do not bruise

- White or light brown reticulation at the top of the stem where it meets the cap

Stout King Bolete var. (Boletus variipes var. fagicola) – Looks just like Boletus variipes described above, except the cap and stem are darker. The cap on this one is very dark brown, almost black and can be patchy. The stem is also darker brown than B. variipes. It may only occur in Michigan.

Summer King Bolete (Boletus cf. reticulatus)

This is the North American species of Boletus reticulatus – the true B. reticulatus is a European-only species. Most N. American texts list this mushroom as B. reticulatus but here, until there is an updated name, we will call it Boletus cf. reticulatus.

The summer king bolete emerges in early summer under hardwood trees; it has a preference for oaks, and specifically white oaks.

Summer king bolete caps are 2.5-7 inches wide, whitish or pale brown, smooth, and dry on top. As it matures, the cap color gets darker brown and may develop cracks or fissures. Under the cap, the pores start out white or dirty-white, then turn olive and brown.

The stems of the summer king bolete are white or pale brown, very thick and club-shaped, and firm. Stems range from 2-4 inches long and 1-1.5 inches thick. They are usually swollen at the base – this is a short and stubby mushroom with a tight brown cap.

At the top of the stem, where it meets the cap, is fine white reticulation. Sometimes, the reticulations stretches down the length of the stem. Summer king stems also are known to “peel” – pieces of the stem detach from the whole, like a strand of string cheese being pulled down.

The flesh of the summer king bolete is white and does not change color when cut. Caps don’t bruise but the stem may bruise light brown when handled.

- Pale brown or whitish cap, darker brown with age

- Cracks or fissures on mature specimen

- White pores then turn olive, then brown

- Stems white or pale brown, bulbous, stubby

- Flesh does not stain when cut

- Caps don’t bruise, stem may bruise light brown

- White or light brown reticulation at the top of the stem where it meets the cap, often stretching down the cap

West Coast

White King Bolete (Boletus barrowsii)

Since this species was described to science in 1976, it was considered a white-capped version of Boletus edulis. However, a 2010 study put this fungi as a separate species.

Many people, and mushroom identification books, still suggest this is a white-capped version of the king bolete (and the common name corroborates it). However, it’s not quite the same, even though it is a close cousin.

The white king bolete grows across the west coast, and is especially abundant in Arizona and New Mexico. This bolete prefers ponderosa pines and coast live oak, but may be around other trees. It emerges in summer or fall during monsoon season in the Southwest, and in fall and winter on the west coast.

White king bolete caps are 2-6 inches wide and a dull white color that turns light brown with age. They are dry on top. The spore surface under the cap starts out white, then turns yellow and finally olive-yellow.

The stems are dense, white, and very bulbous when young. They grow 2-6 inches long and are 1-2 inches thick. However, some specimens I’ve seen pictures of are significantly larger. When young, these mushrooms are quite stubby and squat.

At the top of the stem where it meets the cap is fine white reticulation that may turn brown with age. Sometimes, the reticulation stretches down the stem.

White king bolete flesh is white and does not stain when cut. The stem and cap don’t bruise when handled, either.

- Dull white to light brown caps

- White spores turn yellow than olive-brown

- Bulbous white stems, stubby

- White flesh does not stain when cut

- Cap and stem do not bruise when handled

- White reticulation at top of the stem

California King Bolete (Boletus edulis var. grandedulis)

The California king bolete is a stunner! In looks almost exactly like the regular king bolete, except massively bigger. The caps grow 4-20 inches wide and have stems 3-16 inches long. The California king is found primarily with Bishop pines in central and northern California. It appears in summer and fall at high elevations and through fall and winter in coastal locations.

When young, the cap is tan or brown, then turns darker brown or reddish brown. It is tacky when wet. Under the cap, the pore surface is white but then changes to yellow and dull brown. The pores do not bruise.

The stem of the California king is white, thick, and swollen or club-shaped, especially when young. As it matures, the stem evens out more though the base is usually broader. At the top of the stem, under the cap, there is fine white reticulation that often covers half the stem. The reticulation may turn brownish with age.

California king bolete flesh is white and does not change color when cut. The cap and stem do not bruise when handled, either.

- Massive mushroom

- Light brown to reddish-brown cap

- White spores that turn yellow than brown

- White bulbous stem

- White flesh that does not change color when cut

- Cap and cap do not bruise when handled

- White reticulation at top of the stem

Queen Bolete (Boletus regineus)

The queen of boletes used to fall under the name Boletus aereus, which is a similar looking species from Europe. Now, she has her own species name, as she deserves. The queen bolete is a bit smaller than the California king, like a miniature version. It is also a species that grow in California and the Pacific Northwest in fall. However, instead of only growing with conifers, the queen likes a mix of conifers and hardwoods.

Queen bolete caps start out buff or tan, then turn chestnut to dark reddish-brown. They are 3-6 inches wide and get tacky when wet. When young, the caps might have a white bloom on them – a dusty white powder substance that easily brushes off. Under the cap, the pores are white or cream-colored, then turn light yellow or yellowish olive with age. They do not change color when bruised.

The stems are 3-6 inches long, white or streaked brown, and club-shaped when young. The overall appearance is very stubby and stout. As they mature, the stems become less swollen but are still thick. At the top of the stem is fine white reticulation

Queen bolete flesh is white and does not change color when cut. The cap does not bruise when handled, but the stem may darken slightly.

- Light brown cap darkens to chestnut or reddish brown

- Cap surface tacky when wet

- Spores white when young, then yellow or olive-yellow

- White or brown and white stubby stems

- White flesh does not change color when cut

- Cap doesn’t stain, stem may bruise brown

- White reticulation at top of the stem

Spring King Bolete (Boletus rex-veris)

In 2008, taxonomic studies determined the spring king was not a subspecies of B. edulis, but it is for sure a close cousin. The spring king, as the name suggests, appears in early spring. This is the first step in distinguishing it from the other king boletes which all emerge in late summer or fall.

The caps of the spring king bolete are pale colored, 4-7 inches wide, and often patchy, pocked, or wrinkled. They turn reddish-brown to dark-brown with age. When wet, the caps are sticky. Sometimes they are covered with a silvery-gray bloom, which easily wipes off.

Underneath the caps, the pores are white, then turn light yellow to yellowish-brown.

Spring king stems are white, 2-4 inches long, and bulbous. As the mushroom ages, the stems become pale brown. At the top of the stem is fine white reticulation which darkens with maturity.

The flesh of the spring king is white and does not change when cut into. The cap and stems darken when handled.

This king emerges in spring among conifer and firs, with a preference for montane conifers. The spring king is found in California and the Pacific Northwest.

- Caps are pale to tan to reddish-brown

- Often has a grayish silver dusting on cap

- Cap sticky when wet

- Spores are white, then turn light yellow to yellow-brown

- Stem white to pale brown

- Flesh is white and does not change color when cut

- Cap and stem bruise darker when handled.

- At the top of the stem, fine white or brown reticulation

Foraging King Bolete Mushrooms

Season

Most king boletes grow in late summer or autumn, with the exception of the spring king which comes out in spring. They appear 2-3 days after significant rains. Don’t hesitate to get out there. The slugs will be racing you, and they move faster than you’d expect.

During seasonal drys, they may not fruit very much or at all.

Habitat

King boletes are mycorrhizal, so they develop relationships with specific trees. On the east coast, oak trees are preferred, while on the west coast it’s all about the pines and other conifers. Look into each species to see which tree or trees it likes. This is a great way to start looking for king boletes – identify the trees and season, then look for the emerging kings.

They will always be growing on the ground, never on trees or wood.

Identification

All the king boletes have these seven key things in common:

- Pores instead of gills – All boletes have pores, not gills. This is the first step in identification. Look under the cap to see whether you’ve found a bolete or not.

- White pores that do not stain – The pores of young species are white and dense, like a very thick, firm sponge. As the king bolete matures, the pores naturally turn yellow to yellowish-brown. No matter if the pores are white or yellow, when you cut the pores, they don’t change color. White pores stay white. Yellow pores stay yellow. Many boletes pores change color when cut or bruised – king boletes never do.

- White reticulation at top of the stem – Reticulation is a fancy name for very fine net-like pattern. The reticulation appears at the top of the stem, directly under the cap. In some species, it extends down the stem but for most, it’s just a small section on the very top. The reticulation is white or buff tan. Every king bolete has white or lightly brown reticulation – if you find a bolete without reticulation, it is not a king.

- Flesh is white and does not stain – Many boletes stain red or blue or green when cut. King boletes flesh will never stain. It stays white.

- White or tan stem – The stem is white, sometimes with tan shading or light brown markings. There are not other colors on the stem and they won’t turn different colors.

- Sturdy, firm, dense, often stout – This is a thick mushroom, not easily crumbled, broken, or disintegrated. Sometimes, the cap pops off the stem, but they will both still be firm to handle.

- Tan or brown cap, like a bread bun – The brown often changes to chestnut or reddish-brown with maturity. The only exception is the white king bolete, which of course has a white-ish colored cap. But, even that one changes to brown as it matures.

On The Lookout

Because the king boletes buns are usually tan or brown of some shade, they tend to blend into the forest. This is especially true when they are in prime button stage. The little kings will often be tucked into pine duff or under leaves. Looks for bumps and bulges along the ground, particularly when you’re in conifer or oak forests during the prime fall season. Once they get bigger, they’re easier to spot, but big specimens are way to frequently well-populated bug hotels.

King boletes often grow in scattered groups, but also appear singly with no others in sight. Always look for more if you find one.

Lookalikes

Tylopilus felleus

There is one major lookalike to the king boletes and it’s a doozy. If you ever hear anyone violently cursing while mushroom hunting, it’s because they found an almost-king and were bitterly disappointed. Literally.

Aptly nicknamed the Bitter Bolete, Tylopilus felleus differs in only two ways beside the taste. It’s pores are pinkish and the stem in covered in dark-brown netting. The thing is, the Bitter Bolete gets enormous (caps up to 12” across) and so when you find one, the first instinct is to do the “I found a king” dance. But then, after a nibble test, all hopes are dashed and you are left with a very bitter taste in your mouth and heart. Lucky for west coasters, this mushroom only appears in eastern North America.

Other Boletes

As mentioned before, there are hundreds of bolete species worldwide. Other boletes are commonly misidentified as king boletes because the forager is not doing their due diligence. Remember:

- kings flesh is white and does not stain

- it always has white reticulation (sometimes tan, but always reticulation)

- white or tan stem (no purple, no yellow)

- pores never stain.

Memorize this and you’ll be okay (at least in North America).

King Bolete Common Questions

Can I grow king boletes at home?

No. Unfortunately, due to the mycorrhizal nature of king boletes, they have eluded cultivation. At least for now. However, you will find several guides for growing porcini or king boletes if you look online. And, you will see people selling “seeds.”

This is an excellent example of the internet becoming an echo chamber for false information. Please don’t fall for those scams. If it were possible, major companies worldwide would be growing king boletes by the boatload.

Can king boletes be eaten raw?

Some people do – it is a common practice in Italy. However, we never recommend eating mushrooms raw.

What trees do king boletes grow under?

It varies a bit by region. On the east coast, they grow with hardwoods or in mixed forests. West coast species prefer conifers. Look at the regional guide in this post to see which trees you should focus on in finding king boletes.

Vernon Ullrey says

I found something similar to the King Boletus in Arkansas. I took pictures of them didn’t know what they were at the time. I still have the pictures if you are interested in them

Jenny says

Hi & thanks for reaching out! I’d love to see the pictures! However, I’m not a scientist or mycologist so if it isn’t a known species, I’ll be no help. Even then, I’m just a very passionate amateur’ :-). I’d highly suggest posting pictures to Mushroom Observer (https://mushroomobserver.org/observer/intro) which is like a citizen science documentation of finds.

Michael Evans says

I have found a bunch of what have been identified as a spring king bolete. They are huge! some are 10 inches across! My question is what is the best time and what parts (stem and cap) to harvest them for dehydrating.

they seem to age quickly.

Thanks, Michael

Jenny says

That’s an awesome find! It’s best to harvest them before they get too big — usually the bigger they are, the more bugs there are. Also older specimens will have super spongy pores. If the pores are too beat up and spongy or buggy, I remove them. They scrape off easily with the back of a spoon. If the pores are still white and firm, I leave them on. You can use the entire mushroom for eating and dehydrating. The cap will be the tenderest but the stem is great too. And yes, they do age quickly. You can store them in a paper bag in the fridge for a few days. Also use paper because plastic causes moisture to build up and then the mushrooms decompose faster.

Bob Pflug says

We bought our 88 acre retirement property in 1989 and in 91 our white and Norway spruce plantation was planted. It was in 2021 that we discovered that we had won the king bolete lottery. I made a dryer with a wood box, 2 computer fans and an old cloths iron plus 3 woven 1/2 steel mesh racks. Enough produce was dried to last a few years, fortunately as 22 and 23 appeared zilch. This year I’m super vigilant. Yesterday I discovered 2 very small amanita mascara and a small king nearby. Hoping this the start as they thrive together. Our location is K0B 1J0 Canadian Postal Code on Ottawa River. We are 89 an 90 and hope to dry a large quantity again. Question: are zilch years common?

Jenny says

Oh wow, I am jealous!! There can be slow or non fruiting for sure. So much depends on weather — dry/drought years will produce far less. I’ve found with mushrooms, they can be picky and just not show up if they don’t like the climate conditions. Another thing to be aware of is that they may fruit earlier or later than “normal” some years, also depending on the weather and climate overall. This year in new england everything showed up 2-3 weeks early, possibly bc the climate is warming or because we had a very humid summer

Dan Schmidt says

Great Guide Jenny,

For the past 3 years, I believe we’ve had King Boletes popping up on one side of our home in Seattle, I finally harvested one in great shape and it checks all the boxes for a King. I have no experience in foraging, so I’m timid on wanting to eat it for dinner, but would love to in theory! I found this at the base of a Rhododendron, others grow near some conifers. She’s a real beauty, could I send you a pic?

Thanks again!

Jenny says

Thanks! You can submit photos to our facebook group, make sure to read the id request guidelines https://www.facebook.com/groups/340690111324762