There’s always those that say phooey to convention and grow however they dang well please. The gilled boletes (Phylloporus) are a prime example of this. From the top, they look just like any other bolete, a brownish bread bun sprouting from the ground. But, then, flip them over, and your mind might explode. Those are gills, not pores like every other bolete on the planet. Why?! Gilled boletes frustrated classification for a long time, but the most recent research puts them squarely in with the boletes, despite the gills.

Gilled boletes are edible and quite tasty. They have an earthy mushroom flavor and a dense texture that turns somewhat buttery when cooked.

- Scientific Name: Phylloporus spp

- Common Names: Gilled bolete or golden gilled bolete

- Habitat: On the ground with specific tree species

- Edibility: Edible

Jump to:

All About Gilled Boletes

There are approximately six species of gilled boletes in North America. The most common one is Phylloporus rhodoxanthus (aka Phylloporus rhodoxanthus ssp. americanus), which occurs across most of the country.

Gilled boletes are members of the Phylloporus family. The family name is derived from the Greek words “phyllus,” meaning gill, and “porus,” meaning pore, reflecting its unique combination of gills and bolete-like appearance.

The gilled bolete’s structure led to initial assumptions that it formed a transitional link between the gilled Agarics and the pored Boletes. However, advances in molecular science have since proven that the Phylloporus genus arose from within the Boletes. The gilled structure of the Phylloporus species is a case of convergent evolution – a pored bolete that developed gills separate from any already gilled fungus. So, this is not the missing link ancestor between gilled and pored fungi.

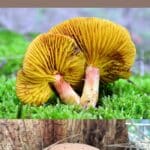

Because of this independent movement to form gills, the gills of the gilled bolete are slightly different from other gilled fungi. They are often cross-veined, meaning there are connecting veins between the gills that form a bit of crisscross (which actually can start to look pore-like if they’re close together). The gills also fork and are often wavy. To the trained eye, they often look “weird” compared to other gilled species. This is often the first clue of what you’ve found – that feeling of “something is odd about this mushroom.”

Gilled Bolete (Phylloporus rhodoxanthus) Identification Guide

Season

In North America, the fruiting season for gilled bolete is summer to fall, typically from July to October.

Habitat

Gilled boletes form mycorrhizal relationships with hardwood trees, particularly oaks and beeches. They grow alone, scattered, or in vast groupings in deciduous forests.

Gilled boletes have a wide distribution across various continents. Phylloporus rhodoxanthus is widespread in North America, and it is also found in Asia (China, India, and Taiwan), Australia, and Europe. Its adaptability and ability to form mycorrhizal relationships with various tree species contribute to its widespread presence.

Identification

Cap

The cap of gilled bolete ranges in diameter from 1-4 inches wide. It starts out rounded, like a button mushroom, then flattens out with age. The cap edges are thin, like a sheet across the top of the gills. This makes the gills very apparent in mature specimens. With age, it may develop a depression in the center that gives it a funnel-like appearance.

The cap surface is dry and often develops cracks as it matures, revealing a pale yellow flesh underneath. Its color varies from brownish to reddish brown to olive brown.

Gills

The gills run down the stem and are thick and widely spaced. They start out yellow, then turn a dirty yellow with age. They may develop a rusty brown reticulated pattern on the stem as the mushroom ages. There are usually cross veins between the gills, sometimes giving them a more pore-like appearance. The gills may fork also. The gills separate easily from the cap, a feature that is common in boletes, but usually, it is the pore layer that is easily removed.

Stem

The stem of the gilled bolete ranges from 1-3.5 inches long. It is typically equal in width and is firm and solid. It may be slightly ribbed near the top where the gills end. The stem is yellowish and often covered with reddish dots and fibrous bits. At the base, there are usually yellow mycelium threads (you’ll have to pull the mushroom out of the ground to see them).

Flesh

The flesh of the gilled bolete is white to pale yellow. The flesh has no distinct taste or odor.

Odor

The gilled bolete does not have a distinctive odor.

Spore Print

The spore print is yellowish to dirty yellow.

More North American Gilled Boletes

Phylloporus arenicola

This rare gilled bolete forms mycorrhizal relationships with pines and is only found in coastal Oregon, Washington, and northern California. It is much smaller than Phylloporus rhodoxanthus, not getting more than 1.5 inches wide. This gilled bolete is a drab olive to olive brown color with a yellowish stem and yellow gills. The gills do not run down the stem or may just a little bit. The stem has reddish browning or hairs on it.

This species grows in sand dunes; the species designation arenicola translates to “growing in sand.”

Phylloporus leucomycelinus

This gilled bolete occurs in eastern North America. It’s also very interesting found in the Philippines. It grows in association with oaks and beeches, just like Phylloporus rhodoxanthus. The cap is chestnut red to dark red and small, not getting bigger than 1.25 inches wide. The gills are yellow, widely spaced, and run down the stem slightly. The stem is yellow with hints of red and is covered with small brown dots.

This species overlaps geographically with Phylloporus rhodoxanthus but is pretty easy to differentiate with examination. It is significantly smaller and has white mycelium attached to the stem base instead of yellow.

Gilled Bolete Lookalikes

This group of boletes has no lookalikes. Those gills under the cap are quite distinctive. The only confusion that might happen is figuring out which gilled bolete you’ve found.

Gilled Bolete Edibility and Culinary Uses

The gilled bolete mushroom is edible. The flavor has been described as “tender and nutty,” and drying the fruit bodies first is said to enhance the flavor.

These mushrooms are quite versatile in the kitchen. They can be sauteed, added to sauces or stuffings, or used raw as a colorful garnish. There isn’t much online about cooking these, but here’s a sweet video of gilled boletes being prepped and cooked.

Gilled Bolete Mushroom Dye

Phylloporus leucomycelinus and Phylloporus rhodoxanthus are used to make mushroom dyes of beige, greenish beige, or gold colors, depending on the mordant used. If you’re interested in mushroom dyeing, here’s a great list from the North American Mycological Association with all the fungi species you can use in dyes. This video details dyeing with a different bolete species, but it is an excellent place to start.

Interested in learning about other edible boletes? Check out all our Bolete guides

Common Questions About Gilled Boletes

Are gilled boletes edible?

Yes, they are edible but not commonly collected because they aren’t super common and its hard to find enough to make any type of meal.

Are gilled boletes medicinal?

There is no information on the potential medicinal properties of this species.

Leave a Reply