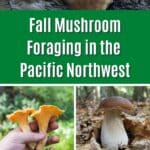

From the golden trumpets of chanterelles to the prized matsutake and the regal king bolete, the Pacific Northwest is a treasure trove of wild edible mushrooms. Fall mushroom foraging in the Pacific Northwest is about abundance, as there’s a lot out there for anyone taking the time to look. The air may be crisper and cooler, but the start of rain brings out all the mushrooms in the forest. And for folks in the Pacific Northwest (Washington, Oregon, Idaho, western Montana, and northern California), fall is prime mushroom hunting time!

Weather plays a crucial role in mushroom foraging, no matter the season. Rain is essential for fungal growth, and in the PNW, you’re lucky to get a lot. Many species fruit after heavy rainfall. However, timing is key. Aim to catch mushrooms when they’re not too dry or too wet. This usually means going out 3-4 days after a good soaking rain. Of course, if it’s raining all the time, you just have to bundle up and get out there.

If I’m missing any Pacific Northwest fall mushrooms, please let me know in the comments! And check out these guide too.

- Winter Mushroom Foraging in the Pacific Northwest.

- Spring Mushroom Foraging in the Pacific Northwest

- Summer Mushroom Foraging in the Pacific Northwest

Jump to:

13 Fall Mushrooms To Forage In the Pacific Northwest

Chanterelles [Cantharellus spp.]

These widespread fungi thrive in established conifer forests, particularly in the Pacific Northwest. They form mycorrhizal relationships with trees, especially Douglas firs in this region. Chanterelles prefer moist, shaded areas with filtered light. Look for them near mossy areas, decaying logs, and in the company of sword ferns and salal. Chanterelles first show up in summer but fruit through fall and sometimes into winter as well.

There are three main species of chanterelle in the Pacific Northwest. All these chanterelle species share some common physical characteristics, including a solid, tapered stem that flows seamlessly into the cap and a tendency to grow in clusters. Their gill-like ridges, which are actually folds of the mushroom’s flesh rather than true gills, are a defining feature that distinguishes chanterelles from other mushroom families.

- The Pacific Golden Chanterelle (Cantharellus formosus) is the most common chanterelle species. It has a vibrant golden-yellow to orange color and a funnel-shaped cap with wavy, irregular edges. The cap can grow up to 6 inches in diameter and has distinctive forked, gill-like ridges running down the stem. Its flesh is firm and white, with a fruity aroma reminiscent of apricots.

- The White Chanterelle (Cantharellus subalbidus) is another species native to the PNW. It has a creamy white to pale yellow coloration and a similar funnel-shaped cap to its golden cousin. The cap is typically smaller, reaching about 4 inches in diameter. Its ridges are less pronounced and more widely spaced than those of the Golden Chanterelle.

- The Rainbow Chanterelle (Cantharellus cibarius var. roseocanus) is a rarer find. Its cap can range from pale yellow to pinkish-orange, sometimes with a hint of lilac. The cap is generally smaller than the Golden Chanterelle; it usually doesn’t get larger than 3 inches in diameter. Its ridges are more delicate and closely spaced compared to other chanterelle species.

King Bolete [Boletus edulis]

King Boletes, also known as porcini or penny buns, are prized for their rich flavor and meaty texture. These mushrooms have a distinctive appearance with a large, convex cap that can grow up to 12 inches in diameter. The cap color ranges from light brown to reddish-brown and often has a slightly greasy texture when fresh – they look like bread buns scattered on the forest floor. Underneath the cap, king boletes have a sponge-like layer of pores instead of gills. The pores start out white and turns yellowish to greenish-brown as the mushroom matures. The stem is thick and robust, usually white or pale cream with a faint net-like pattern called reticulation.

These mushrooms form mycorrhizal relationships with various trees, particularly conifers. In the Pacific Northwest, they’re commonly found under Douglas firs, spruces, and hemlocks. They prefer cool, moist environments and often fruit from late summer through fall, depending on the elevation. Foragers should look for them in semi-sunny spots in the woods, especially on north-facing slopes that retain moisture.

Lions Mane [Hericium erinaceus]

Lion’s Mane mushroom is a distinctive large, white mushroom that grows on trees and logs. The mushroom earns its name from its appearance, resembling a white, shaggy lion’s mane with long, cascading spines. It one of the easiest mushrooms to identify in the wild and a great one for beginner foragers.

The lion’s mane mushroom grows on dead or dying hardwood trees, mainly oak, beech, and maple. It fruits from late summer through early winter, depending on the region. It prefers cool temperatures and can grow up to 15 inches wide. Depending on the exact species, this mushroom can appear as a single clump or in small groupings.

Lion’s Mane is not only visually striking but also highly valued for its culinary and medicinal properties. Its texture is often compared to seafood, with a sweet and slightly nutty flavor. Rich in polysaccharides and beta-glucans, it’s known for its potential immune-boosting and anti-inflammatory properties.

When foraging, look for a white or cream-colored mushroom with long, dangling spines on hardwood trees.

Hedgehog [Hydnum sp.]

Hedgehog mushrooms are easily recognizable by their unique tooth-like appendages on the underside of the cap instead of gills. These mushrooms have pale cream to salmon pink caps that range from 1.5-8 inches in diameter. Their texture is firm yet slightly spongy when fresh. The spines, resembling tiny icicles, are soft to the touch and easily detachable. Hedgehog mushrooms have no poisonous lookalikes, making them an excellent choice for novice foragers.

These fungi thrive in mixed forests with a preference for conifers. They form mycorrhizal relationships with trees, particularly Douglas firs, spruces, and hemlocks. Hedgehog mushrooms often grow in scattered groups across the forest floor, sometimes appearing in fairy rings. Depending on the region, they can be found in the same locations as chanterelles, typically fruiting from late summer through fall.

Lobsters [Hypomyces lactifluorum]

Lobster mushrooms are hard to miss with their bright orange to reddish-purple exterior, resembling a cooked lobster shell. These are complicated mushrooms; they’re the result of a parasitic ascomycetes that infect Russula and Lactarius species. The infection transforms the host entirely. The result is a hard, rough surface without gills, often with a vase-like or irregularly twisted shape. The flesh of lobster mushrooms is white to orange-white, dense, and firm.

These fungi thrive in conifer forests, particularly under ponderosa pines in the Pacific Northwest. They can be found from early August through October, often appearing 4-7 days after a good rainfall.

When foraging, look for bright orange colors among the forest floor debris. Gently wiggle the mushroom free and cut off the base to keep your collection clean. Prime specimens are firm and light-colored. Any that are spongy are past their prime.

Cauliflower [Sparassis sp.]

Cauliflower mushrooms are odd-looking mushrooms that resemble a mass of egg noodles or a brain. They have thin, wavy, crinkled “blades” that are white to pale yellow-tan in color. These mushrooms can grow quite large, ranging from 4-20 inches in diameter. Some specimens even weigh up to 50 pounds. The unique appearance of cauliflower mushrooms makes them easily identifiable for foragers.

These mushrooms are typically found in the fall. They grow at the base of coniferous trees, particularly Douglas firs and pines. They often appear near dead or dying trees, as they are saprobic parasites that cause brown rot in their hosts. Cauliflower mushrooms prefer damp, shady areas and can return to the same spot for several years.

Yellowfoot/Winter Chanterelles [Craterellus spp.]

Winter chanterelles, also known as yellow foot chanterelles or funnel chanterelles, are an awesome find because they almost always fruit in huge colonies. They’re small, so you need a lot to make a meal, but gathering enough isn’t usually a problem. These small, tasty mushrooms often grow in groups in mossy soil or on decaying wood in saturated, cool conifer forests or bogs. They typically appear in late fall and can be found through the winter, especially in milder climates.

Identifying winter chanterelles is relatively straightforward. They have small, yellow-brownish caps with a distinctive depression in the center, giving them a trumpet-like shape as they mature. Their stems are tall, narrow, and mostly hollow, often bright yellow but sometimes dulling with age. The underside of the cap features characteristic chanterelle veins or wrinkles rather than true gills.

Foragers should look for winter chanterelles in dark, wet conditions. They often grow from moss over rotting wood or tree roots. These mushrooms prefer similar habitats to hedgehog mushrooms and regular chanterelles.

Matsutake [Tricholoma sp.]

Matsutake, also known as pine mushrooms, are a prized mushroom species with a distinct spicy fragrance. These elusive mushrooms grow in sandy soil, particularly in the Pacific Northwest, from September through January. The matsutakes have a symbiotic relationship with various trees, especially pines. They can also be found near firs, hemlocks, and other conifers.

Foragers should look for small humps or “mushrumps” in the forest floor, where young buttons have pushed up the pine needle or moss duff. These mushrooms are expert camoflaugers. The cap is white to slightly yellowish, with a strong spicy (red-hot-gym-socks!) fragrance around the gills. Young matsutake have a white veil covering the gills. This veil breaks with age, forming a prominent ring on the stalk.

When harvesting, it’s crucial to be gentle and look for nearby younger mushrooms. The stem butt will always show signs of fine, gritty sand. Matsutake are often prolific, if you see one, search for others!

These mushrooms are popular in Japanese cuisine and are said to bring good fortune when eaten at wedding ceremonies. They can be enjoyed in stir-fries, soups, or grilled for a delicious appetizer.

Honey Mushrooms [Armillaria spp]

These golden-hued mushrooms are sought after for their earthy flavor and slightly sweet undertone. Honey mushrooms grow in clusters on hardwood trees or stumps. Their caps range from 1-6 inches in diameter, with colors varying from pale to yellowish-brown. The caps often display tiny dark scales concentrated near the center. The gills are white to light honey-colored and attach to the stem, sometimes extending down it slightly.

One key characteristic of honey mushrooms is the presence of a ring or partial veil on the stem. However, some species, like A. tabascens, are ringless. The stem itself is tough and fibrous.

Exercise caution when collecting honey mushrooms, as they can be confused with poisonous lookalikes such as the sulfur tuft and various Pholiota species. It’s crucial to thoroughly cook honey mushrooms before consumption, as raw or undercooked honey mushrooms may cause digestive issues. Also, some people may experience gastrointestinal upset even with cooked honey mushrooms, so it’s advisable to consume small amounts initially.

Black Trumpet Mushrooms [Craterellus spp.]

Black trumpet mushrooms, also known as the horn of plenty, are known for their intense, earthy flavor with hints of apricot, making them a favorite culinary species.

These delicate fungi have a distinctive appearance, with a vase or horn-like shape and a dark gray to black coloration. Their thin, hollow structure makes them easy to identify, with no true gills but rather wrinkled or smooth surfaces.

Look for black trumpets in shady, moist areas, often near oak or beech trees. They tend to blend in with the forest floor, making them challenging to spot. A useful tip is to search for mossy areas since they really like that habitat. They are mycorrhizal, meaning they form associations with specific trees.

In the PNW, those trees are varied and you’ll find trumpets in mixed conifer and hardwood forests. They’re most common around coast live oak, tanbark oak, and madrone. Walk slowly and look down for any chance of finding these. They’re worth it! Black trumpets often grow in clusters and can be found from summer through fall.

Oyster Mushrooms [Pleurotus]

Oyster mushrooms have pale, shelf-like caps that can range in color from white to cream, pink, gray, and even brown. The caps are kidney-shaped or fan-shaped and become wavy and curved upwards as they mature. Young oyster mushrooms often have more dome-like or trumpet-like shapes when growing in clusters. Their texture is delicate and slightly rubbery, with a subtle anise-like scent.

These mushrooms thrive in various environments but prefer riparian areas. They typically grow on dead hardwoods and have a particular affinity for alder, cottonwood, and aspen trees in the Pacific Northwest. Look for oyster mushrooms in moist, wet areas such as swamps or riverbeds, especially on dead or dying trees. They often fruit after heavy rains and can appear multiple times in the same location throughout the season.

Chicken of the Woods [Laetiporus]

Chicken of the Woods is a striking edible mushroom that’s beloved for its chicken-like texture and taste. Its vibrant orange-to-yellow coloration makes it easily identifiable in the woods. These mushrooms grow in large, overlapping clusters on dead or dying hardwood trees and can weigh up to 100 pounds.

In the Pacific Northwest, Chicken of the woods grows primarily on spruce, fir, hemlock, and eucalyptus. It’s a parasitic fungus that causes brown rot in the trees it infects, eventually leading to the decay of the tree’s heartwood. The mushroom typically appears in late summer and fall. However, it can sometimes be found in spring or early summer, depending on the climate.

Foragers prize this mushroom not only for its taste but also for its ease of identification, as there are few lookalikes that could be easily confused with it.

Pig Ear [Gomphus clavatus]

This mushroom typically grows in northern mountainous regions and the Pacific Northwest, preferring montane conifer old-growth forests. Its distinctive appearance resembles a pig’s ear, earning its common name.

Pig’s ear mushrooms are cousins to chanterelles and are sometimes called violet chanterelles due to their lilac coloring. They’re also known as clustered chanterelles, although they’re only distantly related to true chanterelles. These mushrooms have a thick stem and a smooth, dry, somewhat rubbery texture.

Foragers prize pig’s ear mushrooms for their meaty texture and earthy flavor. They’re excellent for cooking and hold their shape well during preparation. Popular methods include frying, pan-sautéing, and boiling. They work well in soups, stews, stir-fries, and as a meat substitute.

Unfortunately, pig’s ear mushrooms face habitat loss challenges. They’re considered extinct in the British Isles and endangered across the European Union. While not critically endangered in North America, they’re being monitored due to their rarity and specific habitat requirements.

Where To Look For Mushrooms In the Pacific Northwest

The Pacific Northwest’s coastal forests offer a rich bounty for mushroom seekers. The temperate rainforests, just outside cities like Eugene, provide ideal conditions for various fungi. Foragers can find winter chanterelles, hedgehogs, and even black trumpets in these areas. The dense, mossy-covered trees and undergrowth create perfect habitats for mushrooms. But go prepared, as bushwhacking is also a common part of the foraging experience!

The Cascade Mountains are another prime location for mushroom foraging. Mount Hood, at elevations around 3,800 feet, is known for yielding matsutakes, king boletes, and chanterelles, especially after rainfall.

Urban and suburban areas are also great places to forage. Foragers can explore their own backyards, neighborhood streets, and public spaces. Be vigilant about areas prone to pollution or treated with pesticides. Parks, thickets, and lightly wooded areas with diverse foliage are recommended.

Mushroom Foraging Resources

If you’re new to mushroom foraging, here are some great guides to get started: How To Be A Successful Mushroom Forager, Mushroom Foraging 101, and Mushroom Identification Pictures and Examples.

This guide to the best identification books by region will help you find the best guides for you.

Curious about fall foraging in other areas? Check out our guides for across the US.

- Fall Mushroom Foraging in the Southeast

- Fall Mushroom Foraging in the Southwest

- Fall Mushroom Foraging in the Midwest

- Fall Mushroom Foraging in New England

Common Questions About Foraging Mushrooms In The Pacific Northwest

When is the optimal time for mushroom foraging?

The prime season for foraging mushrooms generally begins in late August and can extend through November, and sometimes into December. The Pacific Northwest is known for its abundance of mushroom species fruiting in autumn.

When can morels be found in the Pacific Northwest?

Morels fruit in the Pacific Northwest in early spring. Check out the spring guide to learn more about morels in the PNW.

Leave a Reply