Elephant ears (Gyromitra brunnea) are a type of false morel that cause a bit of controversy. False morels, in general, cause a lot of disagreement among mushroom foragers, experts, and enthusiasts. Some consider them a delectable edible, while others warn to stay away because they are poisonous. As with most things, the truth lies somewhere in the middle. Here, we’ll discuss all aspects of the beautiful elephant ear false morels, including appreciating them for their unique and fun shape, regardless of whether they belong on the dinner table or not.

- Scientific Name: Gyromitra brunnea (possible synonym Gyromitra fastigiata, but this is also a name for a European species that may or may not occur here, or they’re synonyms for the same species)

- Common Names: Elephant ears, False morel, Gabled false morel

- Habitat: Around hardwood trees

- Edibility: It’s complicated

Jump to:

All About Elephant Ear False Morels

Elephant ears are an eastern and midwestern false morel species. They often look like they have two big ears sprouting out of either side, which is how they earn their common name. Or, they might look more like a horse saddle. These species tend to have wide and varied common names, many region specific or culturally specific. If you know of another one, please let us know!

These false morels vary considerably in appearance, but there are some key points that will let you know what you’ve found. Once you learn to identify elephant ears, it’s pretty easy to differentiate them from other false morels. And it’s very easy to tell them apart from true morels.

The debate over whether this species is edible or not is still debated, but not among true false morel devotees. If you’re unfamiliar with the topic, certain types of Gyromitra mushrooms, specifically Gyromitra esculenta, contain a substance called gyromitrin. When these mushrooms are eaten or heated, gyromitrin is converted into monomethlyhydrazine. Monomethylhydrazine is highly toxic and carcinogenic, and it is even used as a propellant for rockets. What sets Gyromitra apart is that it is not only poisonous when consumed directly, but also when its cooking fumes are inhaled.

But, do elephant ear false morels contain high levels of gyromitrin? And, how much is too much, anyways? Most agree elephant ear false morels are one of the safer species of false morel and there is a history of them being consumed in North America. Still, they are part of the Gyromitra family, so many consider them inedible or too dangerous to try. In the section on Edibility, we’ll dive into this deeper.

Elephant Ear False Morel Identification Guide

Season

Elephant ears are springtime mushrooms, which means they usually appear around the same time as morels between March and May.

Habitat

Elephant ear false morels are primarily found under hardwoods near stumps and downed trees. They seem to prefer hickory and elm trees. They are widely distributed in the Midwestern and Eastern states. They’re officially saprobic but potentially also mycorrhizal, meaning they feed on dead organic matter but can also form a symbiotic relationship with tree roots.

These false morels grow from the ground; they do not grow from or on trees or wood. They grow individually, sometimes in scattered groupings in one area. More likely, they’ll appear at irregular intervals in a forest, growing individually or in small groupings with their preferred tree hosts.

Elephant Ear Identification

Cap

The cap of the elephant ear typically measures between 1-3.5 inches high and 2-4 inches wide. It is most often more wide than it is tall, thanks to the extending lobes, aka “ears.” Caps are a tan to pinkish-brown to reddish-brown color and partitioned into distinct lobes. The lobes branch out from the central stem part of the mushroom and grow upwards to form up and around the stem.

The lobes might be a pair, one on each side like ears or the sides of a saddle with a dip in the center. Or, there might be 3-5 lobes gathered into two or three points, like they’ve been pinched. This creates a more saddle-shaped appearance.

The lobes are loosely wrinkled or crinkled, not uniform, and highly variable. Sometimes, the lobes overlap so much it creates a jumbled look in which the fact there are lobes isn’t immediately apparent. Older specimens usually have more lobes than younger ones. Once you look closer, though, you can almost always pick out the lobes.

There are almost always visible “seams.” These seams are all along the edge of the cap, and look like someone carefully sewed two cap lobe edges together. The seams aren’t always consistent and the entire edges aren’t usually completely fused together, but parts of it are all along the edge. These seams are a key identifying factor.

Undersurface

Elephant ear false morels don’t have gills. Instead, the underside of the cap is smooth and creamy and white to tan. It often looks powdery, too.

Stem

The stem of the elephant ear ranges from .75-3.5 inches long and is broad and smooth without decorations. It often enlarges toward the base, giving it a swollen appearance. It varies in color from pale pinkish-tan to pure white with age. Either way, it is always much lighter in comparison to the dark cap color and creates a distinctive color contrast.

The stem generally appears irregular in shape and is often ribbed near the base. It looks like the stem flesh is folded over in some areas or has deep indents. Stems of this false morel are usually quite ample, often the same width as the cap, which is also quite broad overall. The stem may bruise brown or grayish when handled.

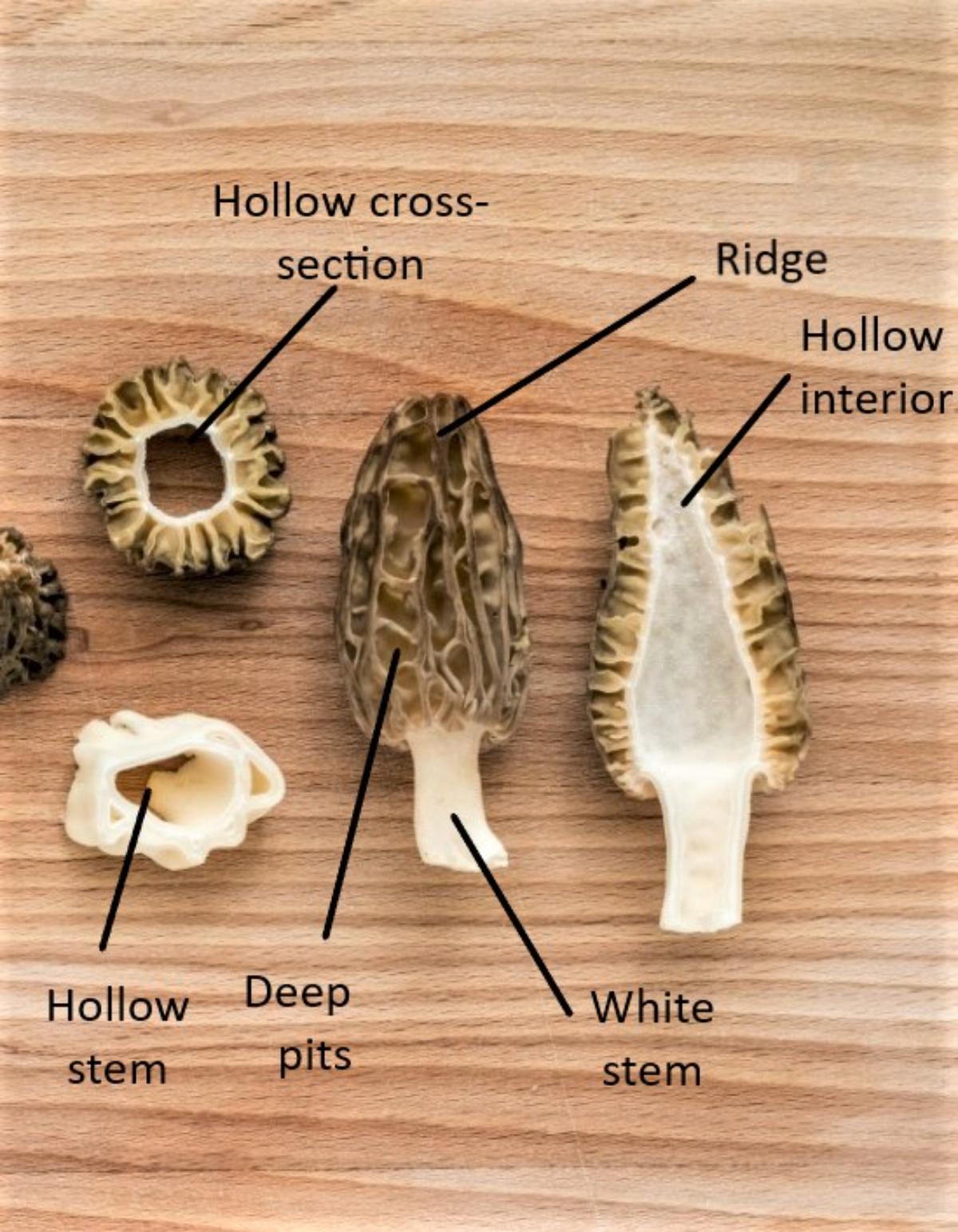

Flesh

The flesh of this mushroom is whitish or flushed rose, extremely brittle, and chambered inside. These false morels break easily if handled too much – the cap flesh is thin and easily fragments. Inside the stem, the flesh is thick, yet there are tons of chambers or tunnels in between the layers of flesh. Inside, the solidness is super dense — it’s like compressed cotton stuffing. The stems of these mushrooms are more solid and hardy compared to the fragile cap flesh.

Odor and Taste

Elephant ear false morels do not have a distinctive smell or taste.

Elephant Ear False Morels Lookalikes

Gyromitra caroliniana, Gyromitra korfii, and Gyromitra montana

These species have a thick stem and a wrinkly brownish head, similar to elephant ears. But they lack the seams along the edges of the lobes. Their caps also tend to be more brain-like than ear or saddle-like in appearance. Caps on these species are attached to the stem, a trait that doesn’t occur with elephant ears. Also, in some cases, the species regions do not cross over.

Gyromitra carloliniana overlaps geographically with elephant ears

Gyromitra esculenta

This species can be easily distinguished by its thinner stems, unlike the elephant ear, which has a stem about the same width as the head. It also has a more brain-like cap shape, and the cap attaches to the stem in several spots.

Gyromitra infula and Gyromitra ambigua

These two have slender stems and caps with a small number of prominent lobes, giving them a more saddle-like appearance. Young elephant ears can be confused with these, but like with other species, the wide stem is a giveaway. Also, neither of these has the telltale seams around the lobe edges.

Gyromitra perlata

This one does not have a stem at all, which makes it look like a cup fungi.

Morels (Morchella species)

Morels have distinct ridges and pits on their heads, unlike elephant ears. If you’re ever in doubt, cut the mushroom open.

Verpas (Morchella species)

Verpas have a head that attaches to the very tip of the stem. They look like tall, slender stems with a thimble balancing on top. Or sometimes like someone pulled a hood down. They are skinnier than elephant ears, looking more like a true morel than a false one.

Elfin Saddles (Helvella species)

Elfin saddles share a cap shape similar to elephant ears, which can cause confusion. There is one key difference, though. Elfin saddles have thin stems compared to their cap size, and the stem is deeply ridged or fluted. Most also aren’t brown, but some are, so color can’t always be relied upon to tell them apart.

Elephant Ear False Morel Edibility: To Eat or Not to Eat

The edibility of elephant ear false morels is a topic of debate, along with all the other Gyromitra species. Some Gyromitra species contain a dangerous toxin, and potential carcinogen.

If you’re unfamiliar with the topic, certain species of Gyromitra, contain a chemical called gyromitrin. Gyromitrin is water soluble and easily converted into monomethylhydrazine (MMH) in the body. Monomethylhydrazine is highly toxic and carcinogenic, and it is also used as a propellant for rockets. The amount of gyromitrin varies by species, location, and a host of other variables that aren’t completely understood yet.

This toxicity leads many to label the entire genus as poisonous, painting the entire group as dangerous. However, others argue that not all species contain significant quantities of this toxin to make them problematic. And, that by warning against all species in this family, we are missing out on some good edible ones.

Elephant ear false morels, specifically, have been reported to be safe when cooked thoroughly. However, caution is advised due to the lack of scientific studies assessing its toxicity. And cooking is a must! Most poisonings come from undercooking or eating the false morels raw.

In general, Gyromitra esculenta is known to be the most hazardous due to its high levels of Gyromitrin/hydrazine. This is perplexing when considering that G. esculenta may be the most commonly ingested Gyromitra worldwide. In Scandinavian countries and Germany, you can find this “toxic” mushroom for sale in markets and even packaged in cans for sale at the grocery store.

The prepared mushrooms are certainly cooked properly to remove the toxins. Gyromitrin is mostly (not entirely…?) removed from false morels by cutting them small and boiling them repeatedly (double or triple par boiling for Gyromitra esculenta). Air drying for a long time also reduces the toxin. And, it is assumed that folks buying the false morels at farmers markets know what the mushroom is and how to prepare it. Unlike the US, there is not a culture of lawsuits for irresponsible behavior on the part of the consumer.

In Europe, there are reports of poisonings, but they are highly varied and unpredictable. These, again, usually revolve around Gyromitra esculenta, not the elephant ears. In these reports, some get very sick after eating false morels, and some even die. However, other people, eating the exact same meal, exhibited no symptoms at all. Still more, others would experience poisoning after previously eating the fungus for years without issues.

While there is no data on the number of people who have consumed Gyromitra without experiencing symptoms, there are statistics on confirmed cases of poisoning. According to the North American Mycological Association’s (NAMA’s) poisoning database, there is only one reported case of poisoning from elephant ears (Gyromitra brunnea), and it was a mild one. For Gyromitra esculenta, there are a lot more reports.

As a result, Michael Beug, the chair of NAMA’s toxicology committee, suggests that Gyromitra brunnea (the elephant ears) should be considered to have the same toxic status as morels: poisonous when eaten raw but safe when properly cooked. Notice it says when properly cooked. This is extremely important. There are methods to remove toxins, if there are any, and they should be followed. No scientific studies have been conducted to assess the presence of toxins in Gyromitra brunnea, though, so the debate remains unresolved.

The exact toxicity of a foraged specimen may depend on where the false morel is foraged from (country, state, county), its age, the time of year, and its genetic strain. It seems that with Gyromitra species, toxicity levels can vary quite a lot between specimens. Some that are fine in one region are high in toxins in other regions. Elevation might even make a difference. With elephant ear false morels, in particular, there is no data showing where they’re “safer.” On the flip side, there is also no data showing that they specifically are dangerous, anywhere.

All that exists is knowledge and cultural practices passed down through generations about how to forage and prepare this species. And the lack of known deaths or even reports of poisoning. All in all, if it were truly as poisonous as some state, we’d probably have heard about it. Or maybe we haven’t because most people strongly and steadfastly avoid all Gyromitra species (at least in North America).

In addition to the issue of whether any Gyromitra species contains toxins, and how much, there is another problem. Recent studies show that gyromitrin (as MMH) is a cumulative toxin. This means that its levels will build up in your body with repeated consumption. This potentially could lead to illness or even death. For us, this is a more concerning aspect compared to its immediate toxic impact.

Please, keep all this in mind before eating. It may be that there isn’t much of a danger since rarely is a person eating enough of these mushrooms to cause extreme danger, but it’s possible. And, with elephant ear false morels, the toxin levels may be so low it doesn’t really make a difference. We don’t know. More studies need to be done with humans first.

It is also important to note that cooking the mushroom may not eliminate all risks entirely, as the fumes released during cooking can also be hazardous if inhaled (also hotly debated, but we prefer caution over carelessness). Some folks report strong gas/petroleum smells and feeling nauseous when cooking Gyromitra, but this almost always is specific to Gyromitra esculenta. In the Cooking section, we give recommendations around this, as a safety precaution.

If you choose to consume these mushrooms, it is essential to be familiar with the signs of gyromitrin poisoning in order to seek immediate assistance if necessary. Symptoms typically start 2-24 hours after ingestion or inhalation of cooking fumes. These may include intense headaches, gastrointestinal discomfort, vomiting, and severe diarrhea. In some cases, the toxin can be more deceptive and cause harm to the red blood cells, liver, and kidneys, which can ultimately lead to death.

Elephant Ear False Morels Cooking and Preparation

If you decide to try Elephant Ears, it’s crucial to prepare and cook them properly. Now, there are a lot of people who have been eating these for decades, and they prepare them differently, and that’s fine. In fact, I’m sure this article will get some pushback about my insistence on proper cooking, which includes parboiling. However, I want everyone who has never eaten these to proceed with utmost caution. Maybe it’s being “overly cautious,” and I’m totally fine with that.

Remember, you alone are solely responsible for your choice to eat these. And it’s up to you how you prepare them.

Do not serve Gyromitra to individuals unfamiliar with the mushroom and the edibility controversy!

Elephant ears have a meaty and savory mushroom flavor, but they lack any real distinctiveness. They taste great but aren’t spectacular. However, due to their size, they make up for flavor in substance and body.

Unfortunately, these are not easy mushrooms to prep and clean. The flesh is brittle, especially in the cap, which can lead it to break apart easily. Also, cleaning these mushrooms can be a pain in the neck. The chambered stem is a common hiding place for insects and spiders. Simply rinsing it off isn’t enough because the water doesn’t get all into the chambers.

To ensure the removal of all bugs, it is necessary to slice and wash each piece thoroughly. Additionally, the stem of the elephant ear tends to contain a lot of dirt. Trimming the mushroom at the base does not help, as the dirt often seeps into the flesh under the cap. Removing all the dirt can be time-consuming and you have to discard significant amounts of the false morel.

When you’re foraging, you can eliminate some of this headache by picking the cleanest looking specimens. With luck, you’ll get some that aren’t to frustrating to clean.

Parboiling Preparation

Parboiling is recommended before cooking. However, be aware that the mushroom’s brittle flesh may fall apart a bit.

- Before cooking Gyromitra mushrooms, open all the windows in your kitchen. Turn on the kitchen hood fan if there is one. Alternatively, you can use a box fan to blow air out of the kitchen. (This may be overkill, but it certainly doesn’t hurt.)

- Boil a pot of water and add the cleaned and prepped false morels (chopped into small pieces and cleaned). Cover the pot and bring it back to a rolling boil. Cook for 10-15 minutes, depending on the quantity, until the mushrooms look wilted and fully cooked. Use three parts water to one part mushrooms.

- Remove the mushrooms from the water and discard the water.

- Rinse the mushrooms thoroughly in clean water.

- Place the mushrooms between paper towels and press to remove excess water.

- Cook up as desired (frying is a standard method)

If you’re interested in further reading and learning more about eating false morels, check out these links.

- False Morels Demystified Facebook Group

- False Morel Mushrooms: Everything You Need To Know

- Gyromitra Mushroom Poisoning

- Historic Edibility Assessments for “False Morel”, Gyromitra esculenta

Do elephant ear false morels have medicinal properties?

Currently, there are no known medicinal properties associated with elephant ears.

What kind of poisonous compounds do elephant ears contain?

They contain gyromitrin (aka MMH) which is toxic when consumed raw. The levels of gyromitrin are not clearly studied, and the amount might vary widely by region.

What are the potential health risks of consuming elephant ears?

As with all wild fungi, you could have an allergic reaction. Also, due to the gyromitrin, you may get sick, though there isn’t enough to be deadly. This is especially true if you eat the mushrooms raw or undercooked.

Finally, some new research suggests that even if you don’t get sick eating them, it is a cumulative toxin. This means that its levels will build up in your body after repeated consumption. This could lead to illness or even death.

Please, keep that in mind before eating. It may be that there isn’t much of a danger since rarely is a person eating enough of these mushrooms to cause extreme danger, but it’s possible. More studies need to be done with humans first.

Leave a Reply