The often-overlooked Dryad’s Saddle is one of the best edible fungi if it is foraged at the right time. It is a unique-looking mushroom that fruits at the first signs of spring and usually again in fall. Dryad’s Saddle season coincides with morel season in spring. When you’re out hunting the elusive morel, keep an eye out for Dryad’s Saddle (Cerioporus squamosus) too!

You may read on other mushroom blogs that this fungus is not a quality edible or even worth searching. I promise you, whoever says that has never eaten a young, tender Dryad’s Saddle mushroom. Timing is everything when foraging. This underappreciated mushroom is dense and meaty with a mild mushroom taste.

Jump to:

All About Dryad’s Saddle

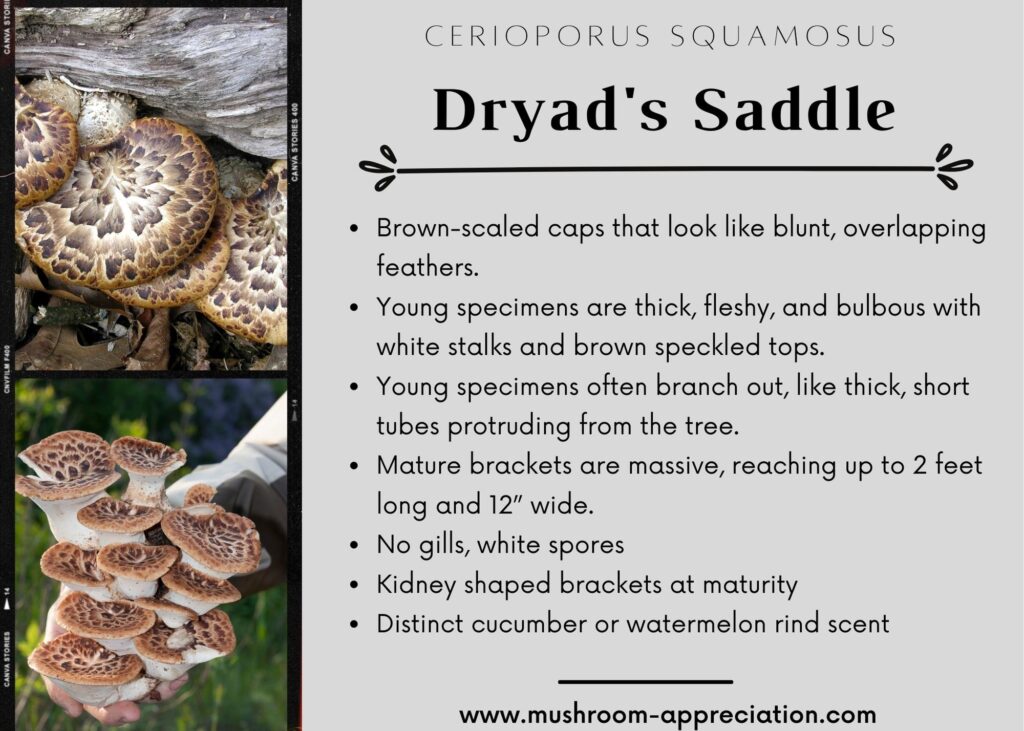

Dryad’s Saddle, also known as Pheasant’s Back and Hawk’s Wing, is a polypore-like bracket mushroom. It fruits on dying or dead hardwood trees. Dryad’s Saddle is easily distinguishable by the cap’s stylish light and dark brown patterns. They look like finely drawn scales or the back of a brown-feathered bird.

This is how it got the common name Pheasant’s back. The Dryad’s Saddle name is based on the dryad nymphs from Greek mythology. The story goes, this mushroom gets so large the dryad nymphs could use it as a saddle. Full-grown specimens can grow to be 2 feet wide!

Dryad’s Saddle is a parasitic saprophyte that causes a white rot disease. It will kill the tree it is attached to if the tree isn’t already dead. It will then continue feeding on the dead tree until no nutrient sources are left.

Where Does Dryad’s Saddle Grow?

This mushroom is found around the world. It grows in North America, Asia, Europe, and Australia. In North America, it is most prolific east of the Rocky Mountains.

How To Find Dryad’s Saddle

Season

As mentioned earlier, Dryad’s Saddle fruits first thing in spring (April – May), usually coinciding with morel season. Then, it will fruit new caps again in the fall once the temperatures cool down. The young fungus emerges after a long soaking rain – the best time to go out looking is 1-2 days after significant rainfall.

They grow extremely fast, so if you want to get them while they’re young and tender, you have to get out looking. Morels are the same, appearing soon after a rain event in spring, so combining these two mushroom hunts makes a lot of sense.

During the summer, the fungus brackets grow to enormous sizes. So, you may find them in summer, but not the ones you want to harvest. Mark the spot, though, to look again in fall to see if there are new growths.

Dryad’s Saddle fruits in the exact location for many years until it runs out of nutrients. The brackets don’t all emerge at the same time. So, if you see evidence of a large colony, check it every week in spring to harvest the newest specimens as they materialize.

Description

Young and old specimens of Dryad’s Saddle look quite different. It’s best to study both because identifying mature brackets will lead you to the young harvestable ones.

When first emerging from the tree, this mushroom looks completely alien. The fungus sprouts out from the tree as a thick, fleshy, bulbous, white protrusion with brown speckles on top. Sometimes just one rounded protrusion juts out from the tree. Often, though, it starts out as one, and then several heads branch out from the shared base, like a multi-headed space creature.

As the swollen growths mature, they flatten out to form brackets. Dryad’s Saddle brackets grow individually or create closely packed overlapping tiers. The thick, fleshy brackets are kidney or fan-shaped and grow up to 2 feet wide and 10-12″ across. They average 2-5″ in thickness.

These fungi don’t have gills; they have white pores that are tightly packed. The stems are the bulbous base from which the fungus first sprouted – thick, short, fat, and fleshy. They’re usually covered in brown speckles but sometimes are all white. The stem stalks rarely are more than 2″ long.

The caps of Dryad’s Saddle make it stand out. They are convex when young, but the outer edges flatten out as they age. Usually, the center remains indented towards the stem and will collect water and tree leaves. The cap is creamy white to light tan with concentric dark-brown and light-brown scales.

The cap color and brown scales vary quite a bit among specimens, with some being primarily tan with a few dark scales and others featuring abundant dark scales. This seems to depend on age and the likely availability of nutrients and sunlight.

Dryad’s Saddle smells distinctively like cucumbers or watermelon rind – it depends on who you ask. It’s definitely not a classic mushroom scent, so be sure to give this fungus a good sniff.

At full maturity, the this fungus is hard to miss. The brackets are thick and vast, jutting out from the tree or stump. Especially large specimens may wrap a quarter or even halfway around a tree.

Habitat

This fungus grows on dead or dying hardwood trees. Long-time foragers of Dryad’s Saddle report that it seems to prefer decomposing elm trees, but this is not conclusive by any means. It is also commonly found on ash, beech, silver maple, box elder, magnolia, poplar, willow, maple, and walnut trees. Dryad’s Saddle isn’t too picky about a host, but it might have preferences.

On The Lookout

While you’re out in the woods, keep your eyes open. There is no real skill or technique in foraging Dryad’s Saddle; you just have to look. Since they are parasitic, they attack the trees they want, but there isn’t a known strategy to it.

The best thing to do is look at the dead or dying hardwood trees around you. Dryad’s Saddle isn’t an elusive fungus. More often, it gets missed because no one is actually looking for it. The mature specimens are much easier to discover since they’re so big and have distinctive markings.

But, first thing in spring, you’ll be looking for the newly emerging brackets. Watch for white bulbous growths jutting out of a tree or stump – they will be fleshy, not rock hard like other bracket fungi. The tops of the protrusions are brown-speckled, and they are often branched into 3 or 4 thick, short stalks. Older dead specimens may be on the ground or still attached to the tree – they turn all black and fall apart as they age.

Dryad’s Saddle Lookalikes

There are no true lookalike mushrooms for Dryad’s Saddle. Members of the Neolentinus genus (Giant Sawgill, Trainwrecker) are marginally similar with overlapping brown scales on their caps. However, they have gills, round mushroom caps, and real stems.

How To Harvest Dryad’s Saddle

Harvest the brackets by cutting them off the tree with a sharp knife. The bulbous stems are quite thick, and since they are fleshy, they won’t just break off. Also, it’s not good to tear them off the tree even if you can because this may harm the underlying mycelium. And, that in turn could upset future Dryad Saddle growth.

The ideal cap size is 2-6″, but this isn’t absolute. Some larger specimens are perfectly edible, while other smaller ones will be tough.

The true test of Dryad Saddle edibility is in the pores. Young, tender Dryad’s Saddle pores are tiny, like little pinholes, and packed together. The pores dilate and broaden as they age and indicate that the mushroom with be tough.

Do a visual check. It takes a little practice to see the variance in pore sizes, but once you learn it, you’ll be able to use this without fail and only harvest the best specimens. You can also scrape the pores with a knife to test age and edibility. Pores that scrap off easily indicate a tender, edible Dryad’s Saddle fungus.

Another method that also works, though not quite as well, is to pierce the fleshy part of the bracket with a knife. If it feels spongy or rigid, the mushroom is not good for eating. However, if the knife pierces easily, the flesh is tender and perfect.

Old Dryad’s Saddle brackets get overrun with bugs and grubs, so always clean and check any specimens before cooking so you don’t get any unwelcome surprises.

How To Prepare Dryad’s Saddle

The flesh of Dryad’s Saddle is thick, dense, and pure white. If it is at all tough to cut, then it will be tough to eat. Discard any portions that are leathery, corky, or rigid. In this way, they are like Chicken of the Woods. If you’ve ever found an old Chicken of the Woods, you know how tough the flesh gets with age – to the point it isn’t worth foraging or eating.

Cut Dryad’s Saddle into thin slices and saute with a bit of oil and salt and pepper. The flavor is light and earthy, slightly mushroomy, and fresh. It is succulent and tender when cooked lightly with a texture much like a portobello. It is important not to overcook this mushroom, or it will toughen.

Dryad’s Saddle is very nice added to stirfries or sauteed and added at the last minute to soups. Use Dryad’s Saddle anywhere you would use sliced portobello mushroom.

History of Dryad’s Saddle

The British botanist William Hudson described this species in 1778 and named it Boletus squamosus. Squamosus is Latin for ‘scales’ or ‘scaly.’ In 1821, Swedish mycologist Elias Fries renamed it Polyporus squamosus, which is still widely used today. However, it was determined recently that Dryad’s Saddle is not a polypore, and it was moved to the Cerioporus genus.

Dryad’s Saddle Quick ID Guide

- Brown-scaled caps that look like blunt, overlapping feathers.

- Young specimens are thick, fleshy, and bulbous with white stalks and brown speckled tops.

- Young specimens often branch out, like thick, short tubes protruding from the tree.

- Mature brackets are massive, reaching up to 2 feet long and 12” wide.

- No gills, white spores

- Kidney shaped brackets at maturity

- Distinct cucumber or watermelon rind scent

Dryad Saddle Common Questions

How long will Dryad’s Saddle keep reappearing on the same tree or stump?

There is no known scientific study on the longevity of the fungus, but this forager has been gathering Dryad’s Saddle from the same stump for eight years, and it is still producing new growths.

Common sense says they will appear every year until the nutrients run out, but it is impossible to say how long that will be for each tree and fungus. Anecdotally, it seems Dryad’s Saddle is a slow parasitic growth and can maintain its development for a long time.

Does the cucumber/watermelon scent remain after cooking?

A little bit, but most of it is usually lost. A lot depends on how you cook it, too. Shorter cooking times preserve the delicate fragrance more.

Can I cultivate Dryad’s Saddle?

Yes, it is possible. However, you’d have to source the mushroom tissue and spores yourself as there is no commercial availability.

Christine Noah-Cooper says

We see a beautiful fungal cascade which is just off-trail on one of our favorite walks. I thought it was Dryad’s Saddle, but now I am unsure. The shelf-like mushrooms are nearly completely white with only a little surface decoration. Some of the mushrooms are a foot across. Can you tell me what I’m looking at? I do have pictures.

Jenny says

Can you post the pics on our facebook group? Pics of tops, undersides are best, also clear ones — fuzzy mushies are impossible to identify lol. I have an idea what they might be but would love to see pics. Facebook group: https://www.facebook.com/groups/340690111324762

Colin says

If it grows on dead or dying wood, it probably isn’t parasitic… One of my favourite wild mushrooms… It looks a bit like a parasole mushroom, which is also one of my favourites…

Jenny says

That’s an interesting point. However, evidence shows that it can cause a tree to die, as well, meaning it is parasitic in some instances. It’s an adaptable fungus, causing some trees to die in order to feed off the nutrients, or taking advantage of already dead wood for nutrients sourcing.

Candice E says

I have a friend who had a Dryad Saddle on his tree. I was excited to see it. A couple days later I went over to see how it had grown and looked under it. IT HAD GILLS.

I was so surprised cause it looked exactly like a Dryads Saddle I never knew there was an imitation. I took photos of it. I had to come here to research what in the word it was.

Jenny says

Can you submit photos to our facebook group – https://www.facebook.com/groups/340690111324762 — make sure to read the pinned/featured post and include all necessary info. Off the top of my head, might be Neolentinus (species dependent of where you live) – https://www.mushroom-appreciation.com/train-wrecker-mushroom.html