** Updated 3/15/2022 to include all North American Chicken of the Woods species

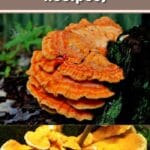

One can easily spot the chicken of the woods mushroom by its impressive size and vibrant yellow-orange colors. This large polypore has surprised many a nature lover the first time they found it! Yet, did you know they’re also edible and considered a delicacy in many parts of the world?

A highly sought-after top edible mushroom, Chicken of the woods is excellent for beginner foragers. There are no real lookalikes, and the bright orange shelf-like growth makes it easy to see. Finding Chicken of the woods (Laetiporus sp.) is known to inspire wild chicken dances in the middle of the forest. With this dense, meaty textured mushroom, you’ll eat well for days.

This mushroom has a lemony, meaty taste. Some think it tastes like its chicken namesake; others describe the flavor as being more like crab or lobster. Whatever your opinion, the chicken fungus makes a great substitute for meat in almost any dish.

Jump to:

- All About Chicken of the Woods

- Where Does Chicken of the Woods Grow?

- Chicken of the Woods Basic Facts

- The Seven North American Chicken of the Woods Species

- East Coast

- West Coast

- Chicken of the Woods Identification

- Chicken of the Wood Lookalikes

- How to Harvest Chicken of the Woods

- Potential for Allergic Reactions To Chicken of the Woods

- History of Chicken of the Woods

- Cooking the Sulphur Shelf

- Chicken of the Woods Recipe

- Common Questions About Chicken of the Woods

All About Chicken of the Woods

Most people refer to Chicken of the Woods as one species, but in fact, there are many. All but one are bright orange or yellow. Chicken of the Woods grows on hardwoods and conifers, depending on the species, and causes brown rot in the host tree. They are both parasitic, attacking the host when it is still alive, and saprobic, living on dead and decomposing organic wood.

Chicken of the Woods is also known as a sulphur shelf, chicken mushroom, and chicken fungus. It earns this common name because it has a similar meaty texture to Chicken, and some even say it tastes like it, too. It is dense, rather bland flavored, and perfect for cooking in everything because it absorbs flavors.

Chicken of the woods is often confused with Hen of the Woods, also known as Maitake (Grifola frondosa), simply because they share a similar common name. They are not alike at all, except they are both excellent edible mushrooms. Many folks prefer using Maitake as the common name for the other mushroom to avoid confusion. We support that! (More info about the hen of the woods, or maitake, is here.)

Even if you never plan on eating one, this is a fascinating mushroom. Let’s learn a little more, starting with some basic chicken facts. We’ll then move on to mushroom identification tips for this species, and close with some cooking advice.

Where Does Chicken of the Woods Grow?

Species of Chicken of the Woods grow across the globe. The majority of them are obvious with their bright orange caps, shelf-like growth, and lack of gills. North America is host to seven Chicken of the woods species, which are separated based on which side of the Rocky Mountains they grow.

Chicken of the Woods Basic Facts

- This mushroom is a polypore, meaning they disperse spores through small pores (holes) on the underside of their caps. You can learn more about poroid mushrooms in this article.

- The different species of the chicken of the woods mushroom are both saprotrophic (feeding on dead trees), and parasitic (attacking and killing live trees by causing the wood to rot). Whatever their method of feeding, you’ll always find them growing on or at the base of a living or dead tree.

- Chickens are easily recognized by their large clusters of overlapping brackets, and bright yellow-orangish colors. The colors fade as the mushroom grows older.

- Many polypores are also medicinal mushrooms, although there hasn’t been much research done on this one. One study has indicated that it inhibits bacterial growth.

The Seven North American Chicken of the Woods Species

Fungi in North America are always a bit behind when it comes to the identification and separation of species. Only recently have biologists and mycologists begun to recognize that the species in North America are genetically different from Europe. Much of this new interest is partly due to our DNA sequencing ability, which opens up whole new worlds of fungi exploration and classification.

As recently as 2001, three new Laetiporus species were identified in North America. These species weren’t new in that they hadn’t been discovered – folks have been foraging them for centuries. But, everyone assumed they were all L.sulphureus, the most well-known Chicken of the woods.

East Coast

Laetiporus sulphureus – This is the type species for Chicken of the woods – it is the primary example of what Chicken of the woods looks like and how it grows. When people talk about Chicken of the woods, this is the specific one they are referring to. L. sulphureus grows in eastern North America, primarily on oak trees. It will also grow on other hardwoods, like cherry, pear, poplar, willows, locusts, and beech.

The most distinctive feature is the bright orange to yellow cap coloring and brilliant yellow spores. Its flesh is soft and thick but gets denser and tough with maturity. The caps often are multi-colored, with deep orange center zones that get lighter towards the edge before turning yellow or white. This species is also found across Europe.

Laetiporus cincinnatus – Unlike other Chicken of the woods, which cause brown rot anywhere on the tree, L. cincinnatus causes butt or root rot. This means it is only found at the base of trees, never further up the trunk. It’s also known to emerge from buried roots far from a tree, which gives the appearance of it being terrestrial. It is not, though, and there are certainly roots below the fruiting body.

Due to its unique growth location, L. cincinnatus develops as a rosette of caps instead of stacked shelves or brackets. The cap of L. cincinnatus is a peachy orange instead of bright orange, and the spores are white or cream. It grows on or around oak trees (almost exclusively) and is found east of the Great Plains.

Laetiporus huroniensis – One of the newly classified Chicken of the woods, L. huroniensis is found in the northeastern United States and northern Midwest. It appears on old-growth conifer logs and is the classic bright orange fungus with pale yellow pores.

Laetiporus persicinus – The white Chicken of the woods, the odd one out that defies the species norm. L. persicinus grows on hardwood and softwood trees and features a white to salmon-pink cap that darkens to deep brown and has white pores. Its range includes the southeastern United States, the Caribbean, Asia, Australia, and South America.

West Coast

Laetiporus conifericola – This western Chicken of the woods is one of the newly classified species. Its range is from California to Alaska, and it grows on conifer trees, preferring fir, hemlock, and spruce. The caps are the traditional bright orange to peachy orange, and the pores are yellow. It is distinct from other Laetiporus species because it grows on conifers.

Laetiporus gilbertsonii – This Chicken of the woods is the western version of the type species Laetiporous sulphureus. It is the classic orange color with yellow pores and grows as many stacked shelves. L. gilbertsonii is found on dead or dying oak and eucalyptus trees. Its range includes the West coast and the southwestern United States. However, there is a variation of this species (L.gilbertsonii var. pallidus) with white pores that grows along the Gulf Coast.

Chicken of the Woods Identification

Chicken of the Woods identification is infamously easy, thus they’re considered one of the “safe” mushrooms for beginners. Of course, I always encourage hands-on education from a local expert, so please don’t rely on just the Internet to learn how to identify mushrooms.

This section is specifically for the Laetiporus sulphureus species, although you can apply most of the characteristics to other species as well.

If you think you’ve found a chicken of the woods, check for these familiar features:

Cap/Stem:

- The sulphur shelf has no real stem. The caps grow in large brackets, which are individual “shelves” ranging from 2 to 10 inches across (about 5 to 25 cm) and up to 10 inches long.

- The brackets are roughly fan-shaped and may be smooth to lightly wrinkled, and oddly suede-like. They grow in an overlapping pattern stacked one on top of the other. Thus the fruiting body can be quite large!

- The outside cap color ranges from bright whitish-yellow to bright whitish-orange. If you cut them open, the inside flesh will be soft and similarly colored. As the mushroom ages, the brightness of the colors fade and the flesh becomes harder and more crumbly.

- The coloring appears in concentric zones, usually brighter orange towards the center and yellow at the edges. This varies by species and maturity of the fungus, though. The more peach-colored varieties can be dark orange in the center and light orange at the edges. Either way, there is usually some type of concentric zonal coloring.

- The caps sport whitish to yellowish pores on the underside, not gills.

- Just emerging Chicken of the woods is bizarre looking – it appears from the tree as a knob. Usually, it is bright yellow, with maybe a splash of orange in the center. Young chickens are often bumpy, brightly-colored erupting cyst-like things. This is before they start forming brackets. This immature stage is perfect for foraging.

Habitat:

It is always found growing on or at the base of dead or dying trees, never on the ground or alone in fields.

These mushrooms grow on dead or dying hardwoods, most commonly oak but also cherry or beech. They’re sometimes found under conifers as well.

Chicken of the woods don’t just grow in forests; they will grow in parks, atop hillsides, along trails and roadsides, and deep in the woods. It is all about the tree. Each species has its preferred tree hosts.

Season:

Most Chicken of the woods species fruit from late summer into fall, August through November. This isn’t always the case, though, and you may find some as early as June. There is no one season where they will all appear.

In fact, it may be that you forage from a tree in August. Then, two months later, when you’re in the same forest, you see another one on a completely different tree. Chicken of the woods operate on their own clock, probably tied to the internal system of the host tree.

Chicken of the woods fruits from the same place year after year, so once you find a spot, mark it down and don’t forget it. However, this comes with a caveat. Weather significantly affects the fungus in creating a fruiting body. Chicken of the woods mycelium lives in the tree year-round – the mushroom we see is just an outward representation and isn’t an essential function for the fungus.

There may be years of drought or too much rain, or just odd seasonal activity when the Chicken of the woods doesn’t appear in its usual spot. Or, it may appear significantly earlier or later than previous years. Unfortunately, Chicken of the woods can be hard to nail down.

It will continue growing from the exact location until it runs out of nutrients. If you’re harvesting from a dead log, the fruiting life is much shorter than from a standing tree.

Spore Print:

The spore print is white, and is a little difficult to get as the caps aren’t so distinct. You probably won’t need a spore print for chicken of the woods identification

Chicken of the Wood Lookalikes

There are no other mushrooms that look like Chicken of the woods. Some people confuse other shelf fungi with this one, but the resemblance is easily disproven on close inspection.

How to Harvest Chicken of the Woods

The best Chicken of the woods is young, tender, and succulent. Young specimens will exude a clear or yellow watery liquid – this is prime harvesting time. The center parts get tough as the fungus matures while the outer edges remain tender. When it reaches its full growth, the entire mushroom becomes woody, chalky, and tough.

Harvest this mushroom while it’s young for the best eating. Use a sharp knife to cut it off the tree. If you’ve found older specimens, only cut off the tender edible pieces. Tenderness is easily determined by cutting a bit off – you can tell by looking at it whether it is tough or juicy. Leave the older portions on the tree or log for bugs and wildlife to enjoy.

Think of harvesting Chicken of the woods like a vegetable. A tomato in its prime is brightly colored, juicy, fleshy, and delicious. A rotten tomato has black spots, decomposed sections, bugs, and smells horrific. Don’t eat the rotten tomato; don’t harvest or eat the old Chicken of the woods.

Potential for Allergic Reactions To Chicken of the Woods

Some people report adverse reactions to eating Chicken of the woods. This usually involves gastrointestinal distress, nausea, and possibly vomiting. Among mushroom groups and social media, there is a lot of hearsay and folklore around this occurrence. Many say that Chicken of the woods foraged from conifer trees are the culprit and warn everyone not to eat these.

The reality is this. Some people are allergic to Chicken of the woods and have adverse reactions. This can happen with every mushroom out there. There is no way to predict how you personally will react.

Chicken of the woods fruiting from hemlock or eucalyptus does seem to present more chance of an allergic reaction, but no scientific reporting confirms this. This warning comes though word of mouth, and how accurate the warning is unknown. Many, many people, and for centuries, have consumed Chicken of the woods from various tree hosts with minimal to no issues.

The only way to know for sure if this mushroom will give you stomach upset is to try a little bit. Pay attention to the type of tree to be aware of the source and then eat a little and wait. This is how you should try every new mushroom, from Lion’s Mane to Morels to Oyster mushrooms. Also, never eat the mushrooms raw – they must be cooked.

History of Chicken of the Woods

French mycologist Pierre Bulliard described this fungus in 1789, naming it Boletus sulphureus. The current designation, Laetiporus sulphureus, was given by American mycologist William Murrill in 1920. Laetiporus means “having bright pores.” Sulphureus means “sulphur colored.”

The largest known Chicken of the woods specimen weighed 100 lbs. It was found in the UK in 1990.

Cooking the Sulphur Shelf

So you’ve found a massive chicken of the woods mushroom, or you succeeded in growing or purchasing one yourself. Now what?

Now it’s time to whip up a batch and see what all the fuss is about! Many people consider chicken of the woods to be a delicacy, with their meaty texture and flavor reminiscent of lemon and chicken.

Some general cooking tips:

- This mushroom becomes harder and more brittle with age, so fresh young specimens are best. Look for caps that are juicy with a tender texture. Ideally they should ooze clear liquid if you slice them.

- I prefer to clean these mushrooms by just wiping them down with a damp cloth. They’re so spongy that regular washing makes them too waterlogged.

- You can store them in a paper bag in the refrigerator before cooking, but no longer than a week.

- Cut your chicken fungi into smaller pieces for easier cooking. These pieces can be blanched, sautéed, fried, or baked.

- If you have too many mushrooms to cook at once, these species will survive a stint in the freezer so sautée them and freeze for later.

- Go easy on the amounts of cooking oil unless specifically deep-frying. These mushrooms can absorb a lot of oil during cooking, making them sit in your stomach like a lead balloon.

- You can use the sulphur shelf in place of chicken or tofu in any recipe. They also work well in curries, rice recipes, risottos, casseroles, or any egg dish.

- Always cook the mushroom thoroughly. Raw mushrooms will very likely give you a severe upset stomach.

Chicken of the Woods Recipe

This easy chicken of the woods recipe was adapted from Italyville.com, an awesome and delicious Italian cooking blog. It’s a simple and tasty way to enjoy their flavor and texture. Serve it as an appetizer, side dish, or add it to meat or pasta.

Ingredients:

- 3 cups chicken of the woods mushrooms, cleaned

- 1 tablespoon olive oil

- 3 cloves garlic, minced

- 2 cups of tomato sauce

- 1/2 cup dry white wine

- Salt and pepper to taste

Clean the mushrooms with a damp cloth, and then either tear or chop them into small pieces.

Warm the olive oil over medium heat and add the garlic. Let it cook for one minute.

Add the mushrooms and cook for 10 minutes, stirring occasionally as they turn a vibrant orange.

Pour in the white wine and cook for another 5 minutes.

Add the tomato sauce and let the whole thing simmer for another 10-15 minutes.

There’s a lot to enjoy about the chicken of the woods, whether admiring its vibrant beauty in nature or exploring its possibilities in the kitchen. Try to get your hands on a specimen and tweak some recipes of your own.

Common Questions About Chicken of the Woods

Can I eat Chicken of the woods from conifer trees?

Yes. But, only eat a little bit first. Some people report gastrointestinal issues, but how common this is is unknown.

Many people eat Chicken of the woods from conifer and eucalyptus trees with no problems. Don’t forget; this can happen with any mushroom, so it’s always best to just eat a small portion the first time.

What is the difference between Chicken of the woods and Hen of the woods?

The easiest way to tell these two edible mushrooms apart is by color. Chicken of the woods is orange, peach, or yellowish. Hen of the woods is gray or brown.

Is it possible to buy Chicken of the woods anywhere?

The local farmer’s market is the best place to look for these delicious mushrooms other than in the woods. Or, check online for foraging groups and see if anyone’s had an incredibly bountiful harvest.

Because it isn’t the easiest mushroom to grow, its availability is limited. This is one of the reasons finding Chicken of the woods is so celebrated.

How difficult is it to find Chicken of the woods?

This mushroom isn’t impossible to find; it’s actually quite widespread and definitely not rare. However, it can be challenging to find nice selections due to their ongoing, hard to predict growing season.

Chicken of the woods fruit throughout the summer into fall, with each specimen on its own schedule. It takes a bit of knowledge, some patience, and luck to find a nice edible Chicken of the woods.

Can I grow Chicken of the woods from a kit at home?

Chicken of the woods is rated as an expert-level home-growing mushroom. You can get sawdust or plug spawn, but it takes a bit of effort and lots of patience to get them producing the beloved mushroom. It may take a year or two to fruit, and the brackets will be smaller than in the wild.

Janice Bamks

What kind of media do I plant the spoors in?

Jenny

Hi! Do you mean for inoculating spores to grow chicken of the woods? The most common method is 2-part. First inoculate sawdust spawn with the spores, then inject the sawdust spawn into oak logs. It’s a bit complicated and not always successful.

If you are referring to making a spore print, since the spores are white, you want to use dark colored paper or glass.

Jo-Anne

Thanks for the great info! I tried to find Italyville.com blog but can’t find it. Can you help?

Jenny

Oh, no. It seems that link got messed up. I’ll update it. Here’s the link you want https://italyville.wordpress.com/2008/07/24/chicken-of-the-woods/

Joseph

Greetings All 🙂

In Hollywood Maryland USA my darling wife brought home some Chicken of the Wood she had collected during her morning walks, and schooled me up real proper-like. C.O.T.W. prepared in a spicy Chicken Curry dish I was extremely hard-pressed to tell the difference between the Chicken meat and the Mushroom.

My darling went-on to dehydrate all of the COTW she could find, and then peddle it on eBay @ $5 an Oz. Lololol

Jenny

Hah, that is an excellent story! Good on your wife

Dan Fracalossi

I found a bunch today

Jenny

Sweet!!!

turnbull tactical and outdoors

one point of contention here. this mushroom ABSOLUTELY can be found growing on the ground. i recent found a large 5lb one growing from the dirt at the stump of a dead tree. i know the mycelium is coming from the roots, but the mushroom was in fact growing out of the dirt probably a foot or two away from the exposed stump.

Jenny

Please see the entry for Laetiporus cincinnatus — it looks like it is growing from the ground but it is always attached to wood underground (roots or rotting wood). The fact that it is attached, even if by very long mycelia, means it is a wood growing species. Congrats on a 5-pounder! That’s a good find!

David Mumbauer

Do Chicken mushrooms freeze well or is there a better way to store them?

Jenny

I find they freeze excellent after being cooked. I’ve never actually frozen them raw, so can’t speak to that. But, when I have a huge harvest, I bake, saute, turn them into chicken noodle soup and then freeze them in portions. They defrost perfectly with no change to texture or taste :-). You can also make jerky out of them which is another way to preserve them for a longer time.

Mike

I just found a wild chicken of the woods almost ready to cut. Is it possible to promote extra growth, spreading or fruiting by drilling a few holes in the log near the existing myshroom ?

Jenny

Congrats on an excellent find! I’ve never heard of anyone doing that before so I don’t know. But it would be a very cool experiment to do! Let me know if you try and how it turns out. I’d be very interested to know. Enjoy that chicken!

Theresa Safdar

I decided this year no more mushroom hunting for me in the woods. It’s just too hard on my lungs. I’m not as young or as healthy as I used to be.

I’ve always enjoyed going hunting for morels. I grew up being taught by old time local experts. This year though I said no more. I will by my mushrooms in the grocery store for now on.

Apparently the mushrooms are not having that. We’ve lived in our home for over two years now. This mushroom has never come up here before and to be honest, though I had heard of them, I had never even seen one before.

This is a beautiful mushroom and 3 days into its growing cycle I believe it is now prime for foraging. I can’t wait to try it!

Jenny

Haha! That’s a riot. And what a fantastic mushie to have growing in your yard!!

Andrea Mueller

How much of a growth can I take before harming the fungus and keeping it from reproducing?

Jenny

So, you can take all of it without hurting the fungus or stopping it from reproducing in that spot. The mushroom you see is the fruiting body — it’s mycelium (roots) are in the wood and safe. HOWEVER, harvesting the entire thing prevents spores from spreading throughout the forest and creating new potential chicken of the wood growths. That chicken won’t grow in that spot forever, at some point it will use up all the nutrients in the tree. So we highly, highly, beggingly implore and recommend only harvesting 1/3 of the find to allow the mushroom to complete its natural biological function and spread spores (which it will only do upon reaching full maturity). This article goes into more depth

Rebecca

I think I found Chicken of the woods in my brother’s woods, but never having seen them before I’m unsure. Can I show you photos?

Jenny

You can share photos in our facebook group. Make sure to read the pinned/featured post and include all the necessary images and information. Fingers crossed its chicken — that would we sweet!