The black staining polypore (Meripilus sumstinei) gets a bad rap, which is really not deserved. It may not be the hen of the woods mushrooms you hoped you’d found, but it’s still a great mushroom. And it’s an edible one when it’s super young. Black staining polypores grow around the world; in North America, it is found chiefly east of the Rocky Mountains, but it also grows in the west.

Jump to:

All About Black Staining Polypore

Like Michael Kuo, I think this mushroom should be named “rooster of the woods,” just to drive everyone crazy. We’ve got a chicken of the woods (Laetiporous sp.), a hen of the woods (Grifola frondosa), and a rooster that will fit right into the coop of conventional naming disasters.

While the black staining polypore looks nothing like chicken of the woods (which is orange), it is incredibly similar to hen of the woods. The similarity is so close that even experienced foragers sometimes get them confused. Once you know the telltale signs, though, it gets pretty easy to tell them apart. All you’ve got to do is a couple of minutes of investigation. I’ll go into more details in the lookalikes section, along with photos.

These polypores are a parasitic fungus that attaches primarily to hardwoods but sometimes conifers. They gather nutrients from the living or decomposing tree and fruit every year in the same spot as long as the tree still has nutrients to give.

This black staining polypore was first described to science in 1905 by William Murrill, an American mycologist. The scientific name Meripilus means divided cap, referring to the many fanned-out cap fronds. Sumstinei honors amateur mycologist, minister, and Pennsylvania school administrator David Ross Sumstine.

North American black-staining polypore is often misidentified as Meripilus giganteus, which is a strictly European species of mushroom. The North American species is very similar but genetically separate. Older guidebooks might have the wrong name listed.

Black Staining Polypore Identification Guide

Season

This polypore appears from spring through fall. Often, they start growing in spring or early summer and then get large in fall. They tend to have a long growing season and don’t deteriorate that quickly.

Habitat

Black stainer polypores grow on the ground attached near trees of their preferred species – oaks and other hardwood species. They do not grow “on” the tree but right next to it or a few feet away. The fungus forms a large rosette cluster at the tree base. It may grow on severely decomposed wood but not an upright tree.

These mushrooms tend to reappear yearly in the same location, as long as the tree roots provide enough nutrients for them to fruit.

Identification

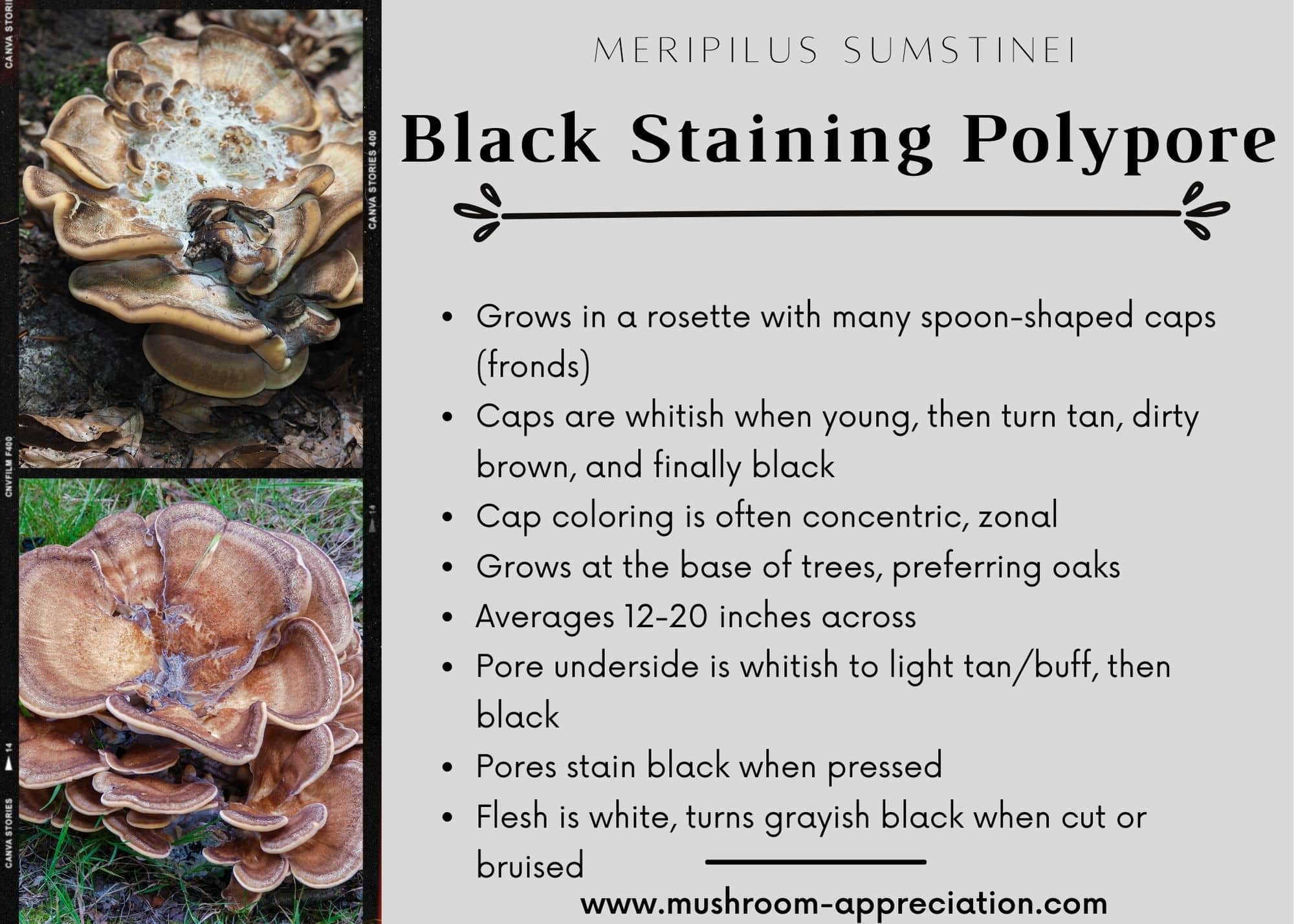

Meripilus sumstinei grows 12-20 inches across (or more) and is made up of multiple caps, or fronds, emerging from a single stem with many branches. The fronds grow in an overlapping rosette form and are not uniform in size. These frond caps average between 2-8 inches wide and are fan or spoon-shaped. They are often slightly hairy and wrinkled.

The fronds vary widely in coloring. They are usually a whitish-tan when young and then turn brownish to black. The coloring is usually concentrically zoned (like a turkey tail), and the colors are muted or dull. Growth at the base of each frond is generally pretty thick, and then it gets thin around the edges. When it is fully mature, the entire fungus will be blackish.

Underneath the caps, the pore surface starts out whitish like the tops. Then, it turns tan to dirty brown to dark brown. The pore surface will turn black if you press on it – this is how the fungus gets its common name. Sometimes, the staining takes a little while to appear, especially in younger specimens. Wait at least 10 min to be sure.

The stem of the polypore is whitish to tan, short and stout, and very tough. It often grows slightly off-center.

Black staining polypore’s flesh is white and firm. When you cut the flesh, it turns darker or black. When the polypore is young, the fronds are very thick, nicely tan or brown colored, and tender. The young specimens look vastly different from the mature ones!

The spore print is white.

Meripilus sumstinei by Zaqri on Mushroom Observer

On The Lookout

Look around oak and other hardwood trees for caps forming on a singular stem. Young specimens are easily overlooked because their coloring blends in with the forest floor. Of course, this is when you most want to find them.

The best way to get good, young specimens is to find mature ones and mark the spot. The following year, get there earlier, and hopefully, you’ll catch them just as they’re fruiting or very soon afterward.

Meripilus sumstinei by Jon Shaffer on Mushroom Observer

Meripilus sumstinei Lookalikes

Hen of the woods aka Maitake (Grifola frondosa)

Most people find black staining polypore mushrooms when they’re hunting for hen of the woods. Hens have an incredible following and are beloved everywhere. The two species are highly similar looking, growing in the same manner with the same type of coloring and overall appearance. It is very easy to tell them apart, though, once you know what you’re looking at.

The primary differences between hen of the woods and the black staining polypore are:

- Black staining polypore fronds stain black underneath when pressed. Hen of the woods caps do not stain when handled. (sometimes to staining take 3-5 min to appear, sometimes it is immediate)

- Hen of the woods fronds are smaller (usually)

- The flesh of the black staining polypore is thicker, especially when young. Hen of the wood’s flesh is thinner and more uniform.

- Black staining polypores usually appear earlier than hens. If you think you’ve found a way-early hen, it’s probably the black staining polypore.

To learn more about hen of the woods/maitake, check out our in-depth guide.

Berkeley’s Polypore (Bondarzewia berkeleyi)

The Berkeley polypore grows similarly to the black staining polypore. It fruits at the base of trees, usually oaks. It is also enormous, way more prominent than the black stainer. It starts out white, looking like the black stainer in youth. However, once the Berkeley polypore reaches its total gigantic growth, it is obvious it is not the black stainer. If you’re unsure, press hard on the pore underside – it won’t stain black.

Foraging Black Staining Polypore

The key to foraging this mushroom for eating is catching it young – very young! It should not be more than 4-5 inches wide or smaller. The bigger it gets, the leathery the caps become until they are absolutely tough and inedible.

Cooking With the Black Staining Polypore

The flavor of the this polypore is unique, deep, complex, and very good. It has an earthy, slightly sweet odor similar to black trumpets combined with portabellos. This forager thinks cooked black staining polypore is highly reminiscent of a rich, well-cooked steak.

The softer outer edges of the polypore are the best for cooking as the flesh gets tougher closer to the stem. When cut, the flesh stains black which adds to its meaty appearance. It will stain other foods cooked with it, so cook it separately or be prepared for your whole dish to be a grayish-black color.

Long, slow cooking really brings out the flavor of this polypore. Cook the outer edge portions well, letting the flavors steep a bit in the oil or butter, or broth. Any stems or tough pieces can be dried, made into powder, and used to enrich broths.

The edges are always more tender than around the stem

Black Staining Polypore Recipes:

Common Questions About Meripilus sumstinei

Can I grow the black staining polypore at home?

Some companies sell spores for this fungus, but growing it is not easy. The exact relationship between tree and mushroom isn’t entirely known – is it purely parasitic or symbiotic in some way? Without knowing the ins and outs of the relationship, it is almost impossible to replicate it.

The best results seem to be growing it similar to hen of the woods, which is also tricky and a lesson in patience. Results often take years.

Is the black staining polypore edible?

Yes. With the caveat that you forage it very young. Or, forage a more mature specimen and use it only to flavor broth. People who say this mushroom is inedible, first of all, are being super lazy. And second, they are seriously missing out on a flavor-packed mushroom.

Shona Patel says

I thought this was hen of the woods and prepped it for dehydration. How I can’t get the black stains off my fingers! Any Suggestions? I hope it is not harmful to the skin.

Jenny says

Oh boy, yeah that black-staining is no joke. Don’t worry, it’s not harmful! I don’t have any surefire tips, except possibly a pumice stone with some dawn soap. I often use mechanics soap for things like this since it’s coarser. Glad you were able to figure out what you had wasn’t hen of the woods. Not a total loss, you can use the black stainer to make a nice stock if it’s too tough for eating.